In previous posts, I discussed nagura stones in general and presented a rationale for a diamond nagura. Here is a report on the development of a diamond nagura.

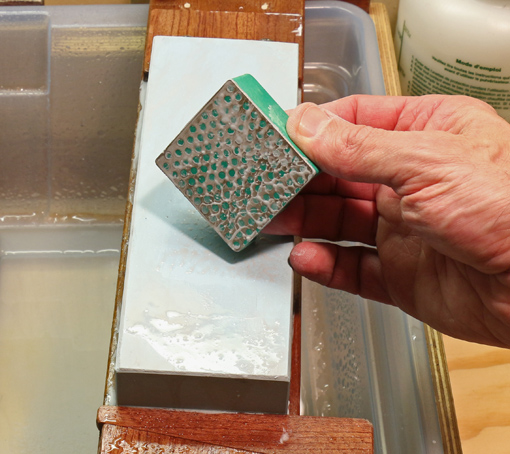

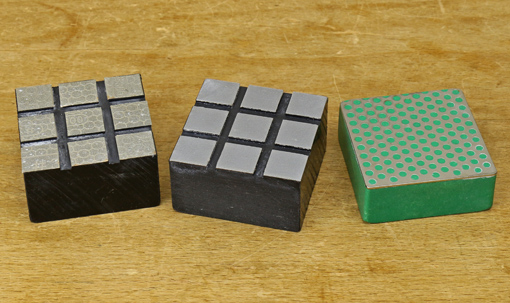

Pictured above on the right is a makeshift first attempt produced by cutting down a DMT 1200 diamond stone. The polka dot surface reduces sticking to the finishing stone but improvement is needed.

The other two naguras were made by routing 5/32″ wide x 1/16″ deep channels in 1″-thick ABS plastic, sawing out 2″ square blocks, and applying PSA diamond sheet to the prominent surfaces. The one on the left is 300 grit and the middle one is 1200 grit.

These channeled diamond naguras work much faster that any other nagura I have used and sticking is completely eliminated. The square pattern of channels allows the user to intuitively retain slurry on the stone or sweep some of it away to produce the desired surface ready for sharpening.

So, returning to the rationale for a nagura, at least two definite nagura functions are expedited: the improvement in “feel and ride” of the blade on the finishing stone with the slurry, and “refreshing” the surface of the stone by removing metal and glazing. Removal of defects on natural stones and perhaps even some localized flattening are also facilitated.

Several questions remain:

1. Does the slurry actually cut steel? I don’t know for sure but the slurry and the action of the nagura are still useful for the other reasons stated.

2. Does the diamond nagura crush the grit particles released from the finishing stone to produce finer particles that cut steel either in the slurry or lodged in the stone surface or both? The lodging effect can be somewhat likened to powdered silicon carbide lodging into a steel flattening plate (kanaban).

3. If that is so, does a 1200 grit nagura crush better and produce finer particles than coarser grits do? As I have mentioned in the past, my sense is that the crushing is real, enhances sharpening, and is indeed better with 1200 than with coarser grits.

In any case, the 1200 diamond nagura test model feels much more friendly on the finishing stone than does the 300 version, which feels too scratchy and harsh.

4. Are diamond particles breaking free from the nagura and thus becoming available to score heavy scratches in the tool? A sharpening stone expert alerted me to this possibility with 1200 grit diamond. So far, I have not noticed this in testing with the 1200 model but I did feel it once using the 300, though the latter diamond film is lower quality.

I wonder if DMT’s “Hardcoat Technology,” which they use on their 95 micron/160 mesh diamond Lapping Plate, could be applied to 1200 grit to safeguard against this potential problem.

In summary, progress has been made but there is more work to do.