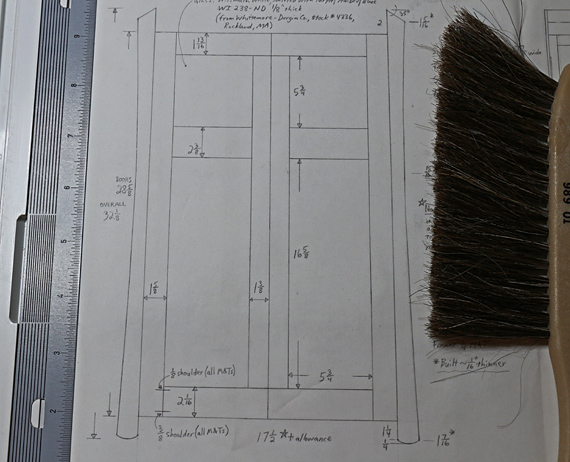

Even at this point, I often make small refinements in the design, mostly to make the proportions look good. I also may add features, such as edge treatments. This is small stuff that I do sweat. I am aiming for a certain peace and balance that will make the piece of furniture be interesting at several levels, and ironically, even fascinating.

However, all of this has to be put into the language of wood. The goal is to make something out of wood, not to just make a nice looking drawing on paper. Sometimes as I gradually get the oversized components out of the rough stock, the wood itself will suggest subtle alterations in the design, so it’s back to the drawing board yet again.

I think of the wood early on in the design process. In fact, I really do not even think of a design in the abstract at all, but instead see it from the beginning as being in a particular wood or at least narrowed to a few possibilities for the wood.

So there is an ongoing interplay among the drawings, the wood, and my imagination.

Now, when the mental dust has settled and sawdust will take its place, I want the wood to be reliable. Oh, and you know where that goes, fellow woodworkers. Recall the words with which the late Professor Bruce Hoadley began his seminal book, Understanding Wood, “Wood comes from trees.” Its essential characteristics make it for good trees; it did not evolve for woodworking projects.

And so the gorgeous boards of quartersawn sapele that I took home for this project were destined to drive me nuts. I wrote about this a while ago in the post “Weird wood stresses stress me.”

This was an unusual, hopefully uniquely frustrating situation with the wood. The point here is that once we have settled on a design that drives us, that answers the question “Is it worth it?” strongly in the affirmative, uncertainty still lurks, starting with the first bite of the saw’s teeth into the rough lumber.

The recipients of our best work do not, in all likelihood, have any idea of this, especially if they are used to veneered particleboard ready-to-assemble “things” (see how civil I’m being). Still, as I pointed out in the first part of this series, these matters are not, and should not be, their problems.

Yet they are out problems, fellow woodworkers, and indeed we can usually solve them. So, I am not whining but once in a while, it is worth mentioning them, just among us. This is the uncool reality that is infrequently shared in print, but we ought to be able to say, “Oh, you too? That happens to you too?”

Next in this series: construction, detours, and, gasp, mistakes!