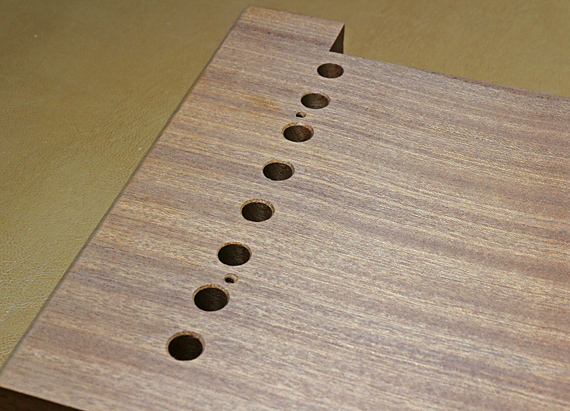

For designing this joint, I suggest 3/8″ diameter dowels for most work with boards about 3/4″ thick. For components 5/8″ thick, 5/16″ dowels are a better choice. The larger diameter dowels create more glue surface area but you do want to have some minimum meat around the dowel in the long grain workpiece.

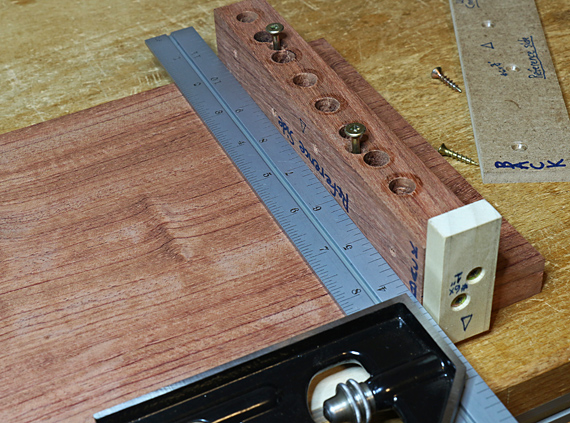

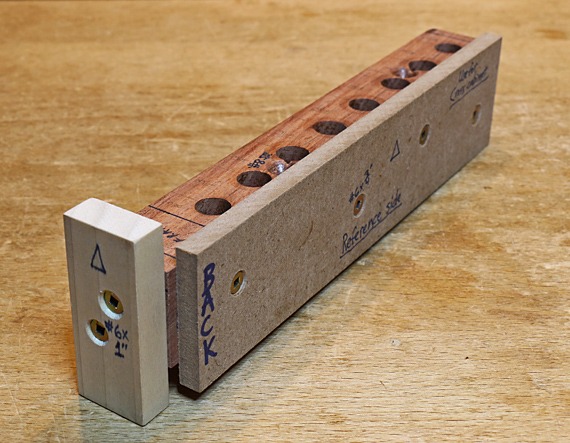

I usually space 3/8″ or 5/16″ dowels about 3/4″ to 1″ apart, on center, as you can see from the jigs, above. Generally, the dowels are closer toward the outer parts of the joint, and spaced wider at the middle of the joint. This is what Krenov taught though I think I am a bit more generous with the number of dowels. You can think of the dowels as individual dovetails.

I suggest the longest dowel penetration into the side grain workpiece that is possible without getting too close to the outside surface. The hole should not go closer than 1/8″ from the outside surface, and actually more clearance is better. Don’t forget the penetration of the brad point of the drill bit, and the soaking of glue, especially in less dense woods. Many of the dowel joints in my pieces take advantage of an increase in thickness of the side grain piece at the joint as part of the design, which works with the structural needs.

The penetration into the long grain piece is less critical because it is long grain-to-long grain gluing. It is not going to fail. 3/4″ is probably sufficient in all cases.

The best dowels ever were Laurier dowels (above). They were made with great precision and consistency. The compressed flutes expand when water-based glue is used in the joint, making for a tight, strong fit. The spiral configuration of the flutes serves to work the glue up and fully around the dowel as it descends into its hole.

Unfortunately, these are no longer available. My stash is getting depleted. Here are some options, though I cannot vouch for any because I have not used these brands yet. None of these have spiral flutes, and the available dowels with spiral flutes are not compressed flutes, as far as I can tell.

When it’s time to for glue up, it’s worth rechecking the hole depths with a go/no-go setting on a calipers or just a stick. You really do not want to be caught in the middle of a glue up with a surprise dowel projection longer than all the others that prevents the joint from closing. If that happens anyway, grab a coping saw quickly.

As for glue (PVA), avoid being too generous. Don’t ask me how I know this, but it is very easy to overload the holes and make a squeezed-out mess all over your carefully prepared components as you draw the joint together. A simple depth gauge with a hole helps to seat the dowels reliably.

I clamp the joint strongly, having prepared whatever pads and cauls are necessary for a true carcase.

You can trust a well-planned and executed carcase dowel joint used in appropriate situations. It is not a difficult or complicated joint to make but precision and care are needed. And no, doweling is not cheating. The key is that it opens up design possibilities with practical construction.