When I first started using dovetail saws there were not many good choices among Western saws. I couldn’t find any high quality, ready to use, new Western back saws so the options reduced to refiling a poorly designed new backsaw, reconditioning an antique saw, using a frame saw, or what I finally chose, using Japanese saws. Over 25 years later, I have to admit that I’m still trying out saws.

And why not? There are great options now available in Western saws, including Lie-Nielsen, Adria, Wenzloff, Lee Valley, and the Gramercy dovetail saw that I now have. My favorite Japanese dovetail saw so far has been the Harima-Daizo rip dozuki, available from Tools for Working Wood. This saw has aggressive rip teeth that can be tricky to coax into a smooth start. A light touch is a must. Once started, the saw tracks extremely well, producing an amazingly clean, thin kerf. There is, however, little room for error. With a saw plate of about .012″ and a total set of about .002″, this thoroughbred does not take kindly to redirection. You’ve got to be on your game from the start.

Japanese dovetail saws in general have some other problems, though all are surmountable. Sighting the line can be difficult in some woods as the saw pulls sawdust toward the marked side of the wood facing you. I do not have the skills to sharpen a Japanese saw. I also can’t fit a fret saw blade in the kerf, so removing waste by sawing involves more steps.

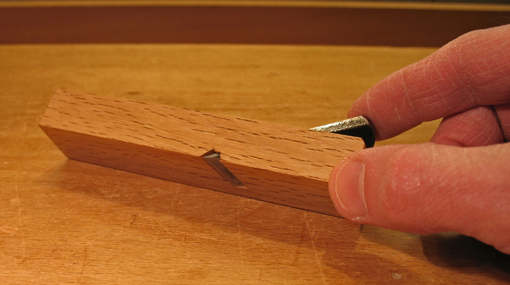

Now to Joel Moskowitz’ masterwork: the Gramercy dovetail saw. It has much of the personality of a good Japanese saw though in the opposite direction with a stiffer blade. It is light weight, appreciates a sensitive touch, and has a tuned, smooth cutting feel. Starting the cut is easy and reliable. The canted blade feels very natural pushing into the cut – notice in the photo that it’s really just the reverse direction cant of a Japanese saw. The kerf is, of course, wider but I contend that thinner is not necessarily better, provided the saw has a proper set. It is the quality of the kerf that matters; it must be have sharp, clean walls for the craftsman to track a line well.

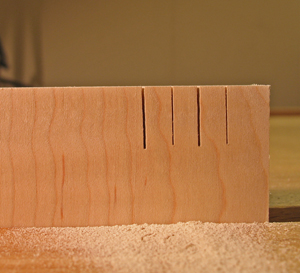

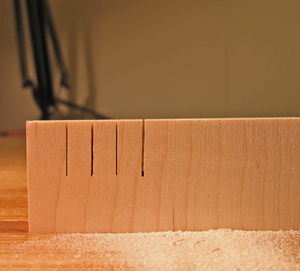

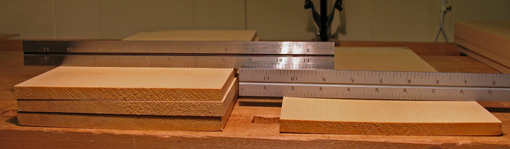

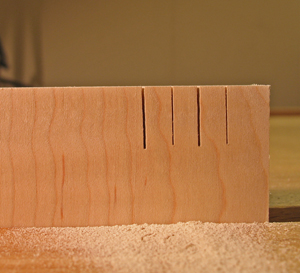

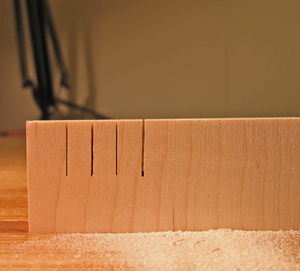

The photos show sharp, clean kerfs from both saws, from the front side (top photo) and from the back side (bottom photo). The Gramercy saw, with a .018 saw plate, 19 ppi hand filed and hammer set about .003 each side, achieves a nice balance between tracking and room for error correction. It cuts about as fast as my Japanese saw – plenty efficient, even in 3/4″ maple or oak.

Excellent Japanese and Western tools are the products of two highly evolved tool systems. They both work, they both have advantages and disadvantages, but most important, a craftsman can adapt to either and do quality work. The choice probably comes down to feel and experience. Birds have feathers, bats have hair; they both fly. I will use both of my saws, I think because I can’t resist either one.

Joel has produced a gem which I highly recommend, especially to devotees of Japanese saws. He even offers a sharpening service. [This review is unsolicited and unpaid. I just like the saw a lot.]