What can someone who just likes making things out of wood humbly learn from a musical genius like Beethoven? I remember reading many years ago a quote by Beethoven that struck me with its depiction of his invincible creativity:

I carry my thoughts about me for a long time, often a very long time, before I write them down… I change many things, discard, and try again until I am satisfied. Then, however, there begins in my head the development in every direction, and, inasmuch as I know exactly what I want, the fundamental idea never deserts me, – it arises before me, grows, – I see and hear the picture in all its extent and dimensions stand before my mind like a cast, and there remains nothing for me but the labor of writing it down…

“my ideas…sound, and roar and storm about me until I have set them down in notes.”

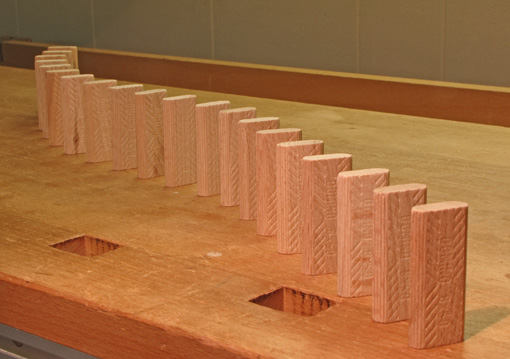

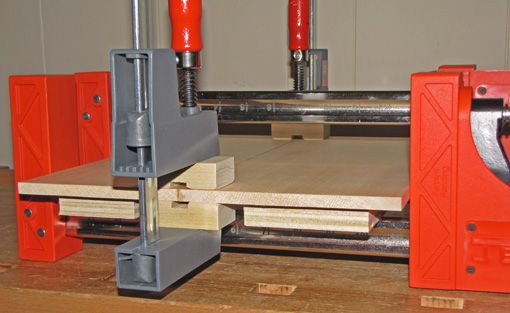

What does this have to do with our little world of saws, planes, and wood? I feel that the really difficult, critical aspects of making a woodworking project are consistency and veracity in design and workmanship – the long line. Success comes from keeping sight of the “fundamental idea,” which one hopes and believes is a good one, through the many steps of a project, while bringing forth the commensurate breadth and depth of technique to render it.

This applies to not only a big project or a tour de force of design and technique, but as well to simple, modest work done satisfyingly well. David Pye, in The Nature and Art of Workmanship, states “Regulated workmanship means workmanship where the achievement appears to correspond exactly with the idea”. The force and clarity of the idea must drive its fulfillment. This is not an easy task.

There’s no delusion of grandeur here; this woodworker is not a speck of a Beethoven. Nevertheless, I do like to make things out of wood, to have an idea and make it be there.

Yea, that’s happy woodworking. Best wishes for your ideas.