I have been using this set of chisels for two years now as the primary chisels in my shop, mostly for chopping joinery but also for many general chiseling and paring tasks. They are beautiful. “Blue paper” steel has been laminated to the soft steel body which has been repeatedly folded to produce a wood grain pattern (mokume). While it was not easy to part with the money to buy them, they have been well worth it.

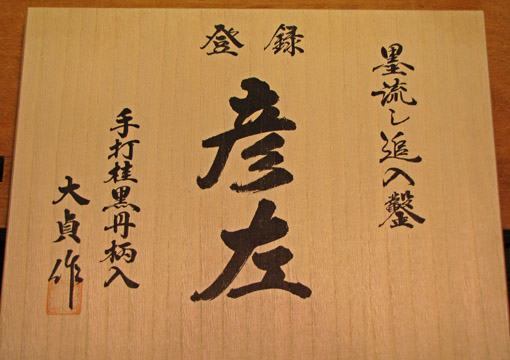

These chisels, with the exception of the handles, were made in the hands of one man, Teiichirou Ohkubo, who uses the market name “Daitei,” in his very small shop in Yoita, Niigata, Japan. (Spellings of his name vary among Western sources.) He works at a forge established about 100 years ago by his grandfather. I am inspired working with these chisels because, though I will likely never meet Mr. Ohkubo, I sense a personal connection with a craftsman putting some of his spirit into his product which, in turn, assists me in doing the same. That’s a good feeling.

The handmade inscription on the box in the photo below reads, I am told, “made by Dai Tei,” in the lower left corner, above the red personal mark (chop).

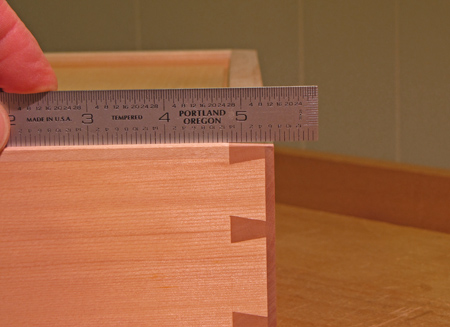

Now for the best part. They have been easy to sharpen on Shapton stones and hold an edge magnificently. I use a primary bevel of 27.5 degrees and a secondary bevel of 32.5 degrees. This gives excellent penetration and completely avoids chipping of the edges. Sometimes, just for curiosity, I’ll pause fairly well along in chopping some joints and am amazed to see the chisels can still shave hair on my arm.

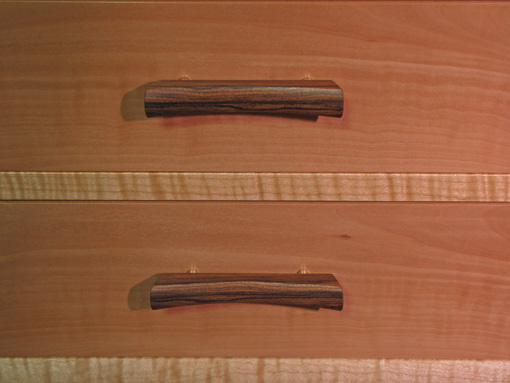

They have an authoritative weight and balance in the hand. I have long enjoyed the ergonomics of Japanese chisels though I recognize this is a matter of personal preference. I believe the handles are Macassar ebony, contrary to the vendor’s description. Initially, I had some concerns regarding the handle wood being perhaps too brittle and prone to splitting. I properly set the hoops (I like Joel Moskowitz’ excellent step by step method), and, despite some serious working action with a mallet, have had no problems.

Any imperfections? Yes, of course, but not enough to cause practical problems. The handle on one of the smaller chisels is undersized and there is slight inconsistency in the angles of the side bevels among some of the smaller chisels.

It is exciting and motivating to work with personally made woodworking tools. Woodworkers now are fortunate to have this kind of tool available from not only Japanese makers, but, more than ever in my lifetime, from many outstanding Western toolmakers. By all means, seek out and use some of these personal tools for personal woodworking.