Remember the old joke about the lost tourist in New York City who asks a local, “How do I get to Carnegie Hall?” The reply: “practice, practice . . .”

I am sometimes asked by novice woodworkers how best to acquire and practice skills. Well, aside from exploiting the myriad sources in media and in person, one must get into the shop, practice, and make sawdust. The inquiry truly applies to woodworkers at all general skill levels who are broadening or deepening their involvement in the craft. Woodworking is a vast field and no one is an expert at all phases, so skill acquisition is an ongoing issue for all of us.

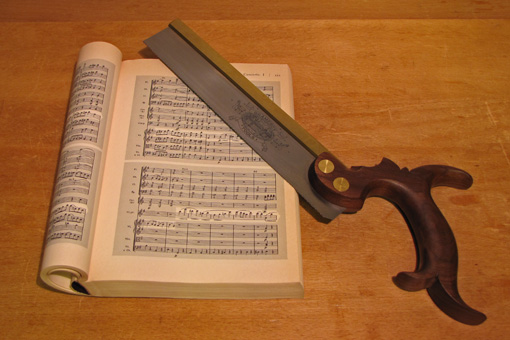

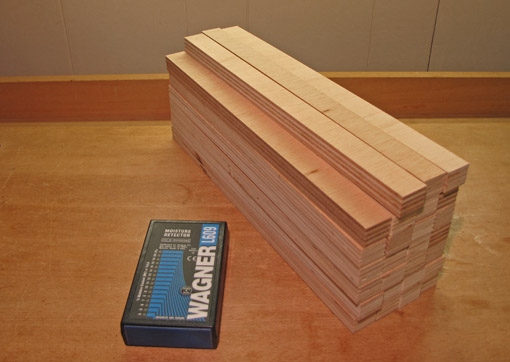

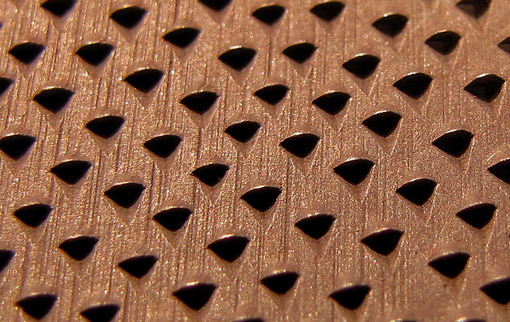

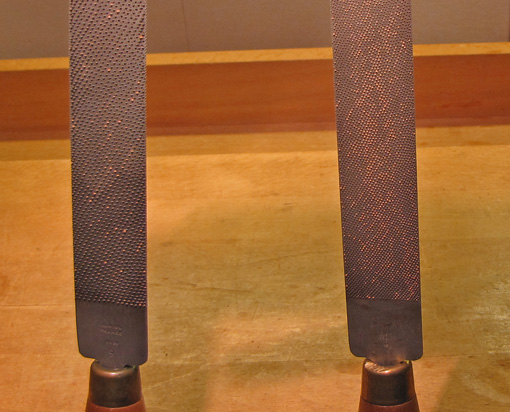

Here is my suggested approach. Let’s say one wants to learn hand cut dovetailing. I would start with isolating the process. Prepare some short pieces of easy-going poplar and cut joints. Ponder and practice layout, sawing to lines, chopping, and so forth. Think about what went wrong, tune your tools, test the limits of accuracy, and experiment. This is like practicing scales in learning a musical instrument. I would not start with a drawer, or even a box, because that creates too many distractions from the core technique.

However, I would soon, very soon, make something with dovetails. It should be a simple, manageable project that might generate some discomfort but not beyond what you feel you can reasonably handle. I would not await perfection in “practicing scales” because there is no such thing, it will be boring, and sooner or later, you have to integrate that core skill into making a bit of music. The music makes the skill meaningful.

So make a little etude piece of woodwork. Simple can be interesting. It will not end up on the back cover of Fine Woodworking. So what. It will contain some mistakes and you won’t be able to correct all of them. So what. It will, however, be yours and will bring you some quiet joy.

Forging ahead, try a small drawer. Now your dovetail “scales” and “etude” experiences will be used to make another box, but this time it will have to fit neatly into a case, which itself will have to be properly constructed if there is to be any chance at all of a good fit. You are integrating skills and they are thus becoming more meaningful.

You will be subtly adapting your dovetail skills to suit a more complex construction. Your designs, aesthetic desires, and the functional requirements of the piece beckon for further refinement of the core skill. Thus you are developing beyond a technician to a craftsman. The music’s beauty is the ultimate impetus to the dance of the fingers on the strings. This is fine woodworking that embraces technique but with a purpose beyond technique: to create a fulfilling piece of personal woodwork.

I think I am a good self-teacher, but at various times I’ve made mistakes at all of these stages. I’ve dwelled too long on isolated technique, overreached in attempting projects I wasn’t ready for, and inhibited my design ideas from fear of breaking new technical ground. That’s the other thing about practicing and getting good at woodworking, you will never stop making mistakes. You will, however, understand them and know what to do despite them.

Happy woodworking indeed!