When considering the benefits of beautifully sharp tools, what usually comes to mind is a smoothing plane producing a cosmetically flawless surface on the wood. This is often the impressive conclusion of a sharpening demonstration.

Sometimes it is the joyful ease of pushing a sharp blade through the wood that compels us to accept our sharpening chores.

No question, these are important reasons to hit the stones. However, I suggest that the foremost and most common reason to use a sharp tool is to be able to work accurately. I’m guessing that may not be what you usually have in mind when you go to the sharpening bench, but consider this: you pretty much always want to work accurately when you pick up an edge tool. You assume that.

It’s simple: a sharp tool immediately cuts the wood, and cuts just where you want. (And in small increments if needed!) The result equals the intention.

A dull edge is more likely to be diverted by the fiber structure of the wood, or tear the wood before it cuts it. Forcing a dull tool can cause you to overshoot or just miss the mark. Of course, all of these problems and others reduce accuracy.

Here are a few examples. The final shavings with the jointer plane to produce an edge-to-edge joint must be easy, thin, and precise to produce that square edge with a tiny camber. Just a very few thou matter, and if your blade cannot easily pull thin shavings, you cannot dial in that accuracy.

Similarly, trying to shoot an accurate end grain edge with a dull blade is like trying to produce calligraphy with a crayon.

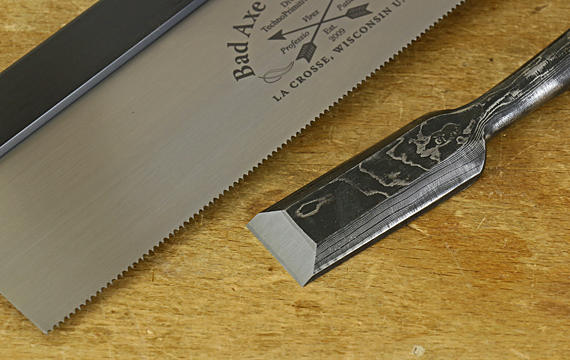

Consider paring a hinge mortise or a tenon cheek. You intuitively know that you want a sharp edge. Less obvious, consider chopping to the baselines of dovetails. You know the dull chisel is slower but think about that first entry where you want to avoid push back against the gauge line. Accuracy requires sharpness.

The same goes for sawing. Sure, the sharp saw is faster but most important, it is accurate.

And so forth.

Working wood is way more fun than working tool steel (aka sharpening), so we need a darned good reason to get over to the sharpening bench. The foremost and most common reason is to work wood accurately.