For general small to medium crosscut work, including precision cutting of tenon shoulders, the Gramercy crosscut carcase saw, pictured at top, above, is a great performer. I seem to always be picking it up for something or other.

Like other saws from maestro Joel Moskowitz at Tools for Working Wood, this relatively lightweight saw starts precisely and moves through the cut with smoothness and efficiency rather than brute power. I find the balance and feel of the saw give me a good sense of the vertical orientation of the blade. The blade is 12″ long, 0.020″ thick, and the 14ppi crosscut teeth are filed with a 14̊ rake and 20-22̊ degrees of fleam, and set about 0.004″ each side. It costs $189.95.

Note that the blade is “canted,” meaning that the depth decreases toward the toe. A feature often found on old saws, it is lacking in most new backsaws. I strongly favor this design. The workpiece being sawn with a backsaw is typically at workbench height. There your natural forward push stroke is augmented by the tooth line sinking deeper as the momentum of the stroke builds. This slicing attack gives controlled power to the cut.

Look at nearly all Japanese saws. They too are canted, but, of course, in the opposite direction since they cut on the pull stroke. The tooth line is not parallel to the handle.

Sharing some of the duties of the Western carcase saw is the Gyokucho “05” kataba (single-edge) 255 mm (10″) crosscut saw. This has a 0.020″ (0.5 mm) saw plate, 0.030″ kerf, and 20 tpi. It is available from Japan Woodworker for $36, item #19.105.0, with replacement blades for $20, and from Hida Tool for $28.40, item #D-GC-#105, with replacement blades for $19.50. This very clean-cutting saw tracks a line extremely well, but, unlike a Western backsaw I don’t get the same feel for vertical with the light, backless kataba. Because this saw is backless, it can make deeper cuts than the Western backsaw, but is not suited for shoulder cutting, a job handled by the stiffer crosscut dozuki or Western carcase saw.

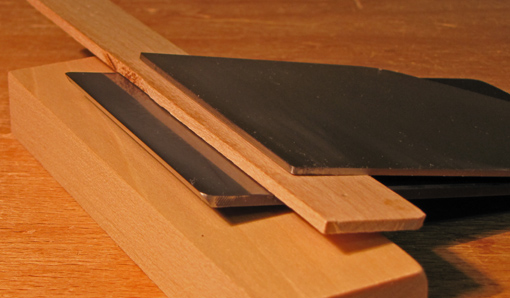

These saws are often used with a bench hook and, as you might guess, my workaday version, seen above, (which really looks like it’s due for an upgraded replacement) accommodates both push and pull saws by having its fence in the middle. When cutting small work with a pull saw, I place the wood on the far side of the fence, and the bench hook itself is stabilized by leaning my weight on the heel of my left hand against the fence. Alternatively, for larger work, the bench hook is simply clamped in the front vise. The push of a Western saw automatically stabilizes the bench hook against the edge of the bench as my hand pushes the work against the near side of the fence.

Once again, we have more than one good way of getting a job done.

Next: handsaws for stock breakdown.