This wood has beauty, strength and variety. Its deep color, density, and figure impart a certain gravitas to a piece. In no sense is this wood a lightweight.

Plain (non-figured) bubinga’s brick red color is accented with darker annual ring lines. These are thinner and more subdued on the rift surface and more variable and bold on the flatsawn surface. Figured bubinga, well, wow! My favorite is the swirly “waterfall” figure, a variant of quilt, which is showiest on the flatsawn surface, becoming a slightly more modest ripple on the rift surface. This species can also produce fantastic broad, ropy curly patterns and pommele figures.

Bubinga (Guibourtia spp.) is available in clear, wide, long lumber. I suggest inspecting the boards for compression failures which seem more common in this species, perhaps occurring when these big trees are felled. These appear as jagged cracks running across the grain and are often very difficult to see on the roughsawn surface.

Giant highly-figured slabs, if you can pay for and haul them, can make fabulous table tops. An internet search will reveal some monster chunks of wood. Veneers are available, with the rotary-cut variety being known as kevazinga (variable spelling).

Below is a sampling from the shop. From top to bottom: rough flatsawn, machined-planed 8/4 rift leg stock, machine-planed rift waterfall with a coat of lacquer.

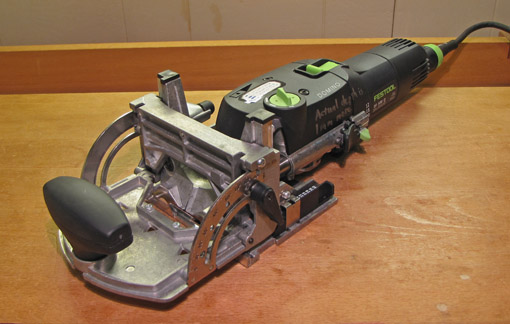

Bubinga works reasonably well, at least the non-figured boards, despite its high density, listed variably in the 0.75+ range (sugar maple is about 0.63). It can be hand planed and sawn well, although more muscle is required than for domestic hardwoods. Likewise, take only small bites when chiseling. Cutting on the table saw requires plenty of horsepower and a good sharp blade to move the stock with enough pace to avoid burning. To prepare leg blanks from 8/4 or thicker stock, I prefer using my bandsaw in conjunction with the jointer and planer instead of my 3HP cabinet saw.

Surprisingly, figured bubinga can often be hand planed reasonably well using a 55-60̊ cutting angle. If that doesn’t work, no worries, because the wood scrapes exceptionally well with card scrapers and scraper planes, even wildly figured stock. It responds well to using a scratch stock to create beading and other profiles. It sands to a high polish. The wood holds edges very well and end grain cuts particularly cleanly.

For finishing bubinga, I like wiping varnish, not too thick, as always. In some cases, preceding with an oil-varnish mix can enhance the look of highly figured pieces, but experiment because sometimes that can result in a muddy look.

I’ve read that bubinga can sometimes be troublesome to glue but I have not had any problems using PVA glues in edge-to-edge and other joinery. Two-part urea formaldehyde glue has worked well for laminations – URAC 185 dries to a dark maroon which blends with bubinga’s color.

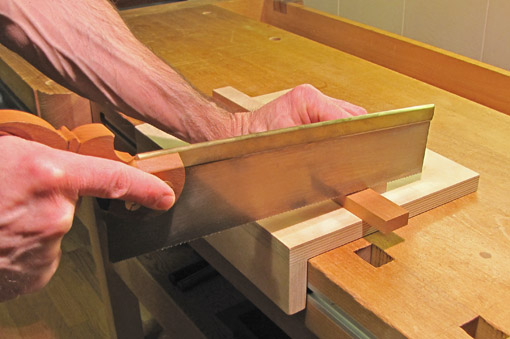

Shrinkage is listed by the Forest Products Laboratory as a decent 8.4 tangential, 5.8 radial, 14.2 volumetric with a very good T/R of 1.45. Most of its strength properties, including its freakish shear strength, are about 50% higher than domestic tough guys white oak and hard maple, while its side hardness is about double of those. It is an excellent choice for shop tools and fixtures such as the dovetail markers and lamp mount pictured below.

If there is a downside to bubinga, it is that it can be tiring to work with, sometimes producing a bit of a love-hate feeling on my part. This is a heavy, dense, and unyielding wood. Parts must mate well – there’s no helpful mush factor in fitting joints. After completing a project in bubinga, you might feel a longing for some friendly walnut, but after admiring the finished piece in bubinga, you’ll soon have ideas to use this wood again.