First and foremost, a woodworker needs to know wood. No degree of prowess with tools and techniques can compensate for a lack of understanding of the material into which steel cuts. The guys at American Woodworker magazine have put together a sawdust-in-your-pockets practical collection of topics that I think would benefit any woodworker: Getting the Most From Your Wood-Buying Bucks, published last year. My recommendation is unsolicited and uncompensated; I just want to share good information.

The sections of the book are:

- Finding Great Wood. This includes getting wood from locally cut trees, using salvaged wood, dealing with wood defects, and understanding lumber grading.

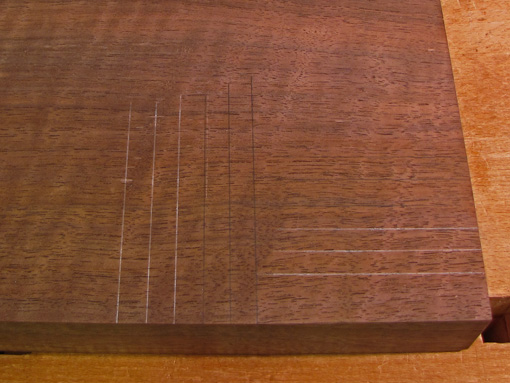

- Sawing & Milling Great Wood. Topics include flitch-cut logs, resawing, milling rough boards, and the best explanation of reading grain direction that I’ve ever read.

- Drying Your Own Wood. Even though you might not use the plans to build your own kiln, the explanations of drying wood and moisture meters are very helpful.

- Very Special Wood. My favorite section. Five different authors share their intimate knowledge of eight different wood types and species, such as spalted wood and mahogany and its look-alikes.

- Special Finishes. This is a sampling of finishing strategies and principles for woods including pine, walnut, cherry, and oak.

- Projects for Special Wood. Here are some interesting furniture projects and techniques for managing large slabs.

Even in areas where I think I have a good amount of knowledge and experience, I was able to pick up useful tips and helpful clarifications. Typical of Fox Chapel books, the layout and photography are attractive and inviting.

What I do not like about this book is the title. The book does give information for you to achieve that goal but, as a title, it underestimates the scope and value of the contents. One of the reasons I wanted to write this review was my concern that the book might be overlooked because of its title.

I’ve tried to open the cover for you in this review, but I think if you take a look for yourself, you’ll like it. Its practical approach makes it a good addition to books I’ve previously recommended: Understanding Wood, by Bruce Hoadley, and the encyclopedic volumes, Wood, by Terry Porter, and Wood Handbook, from the US Forest Products Laboratory.

Don’t you just love wood?