This is really about efficient use of existing space. To actually make more space would involve things such as moving to a new building or knocking down walls – difficult options for most of us. So to make the most of what you’ve got, think beyond the square feet of floor space, look up, and think vertical and volume.

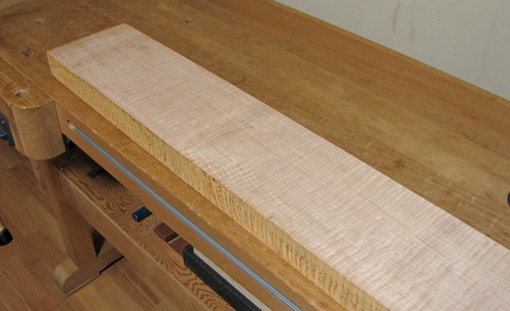

Loving wood as I do, my small shop was getting cluttered with the lovely stuff and I was no longer at ease in my little playground. After a few minutes of sitting on my workbench and staring at the walls, I began to discern where empty vertical space could open up after only minor rearranging.

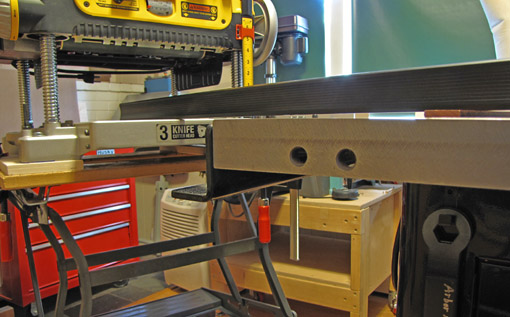

I installed two inexpensive Portamate wood racks after being reassured by a structural engineer that the wall studs would easily take the 500+ pound loads. Instead of the shorter screws that came with the racks, I used 4″ TimberLok heavy-duty wood screws (and grade 8 hardened washers) since about 1 ½” of the screw length is taken up passing through the brackets and spacers. The top photo shows a rack installed in a small alcove that was previously underutilized.

Because most of my woodworking is not large scale work, most of the wood I have in storage has been crosscut to about 4 feet long or less. However, the capacity to store some long boards for a long time is still necessary. In the photo above, notice the two utility hangers toward the right, near the top of the wall. Without interfering with anything else in the shop, they make use of the space above the door to allow storage of boards 8+ feet long. The Portamate rack has also opened up more space for the scaffold-type rack that is below it (beyond the frame of the photo).

I am once again at ease in my space. This helps clear my mind as I am working and makes the work more pleasant. Ahhh, the shop.