Here – we – GO!

Let’s look at building a wall cabinet with two frame-and-panel doors. The style can be Krenovian, Arts and Crafts, Shaker, whatever you like. The same principles can be applied to other casework such as boxes and chests. I will make the somewhat artificial distinction between a table saw-centric and a bandsaw-centric craftsman. As discussed in the previous post, this is not a question of using one machine to the exclusion of the other, rather it is about which tool tends to guide your approach. Furthermore, this does not imply that one machine defines a craftsman’s entire methodology; obviously there are other tools in the shop.

Wood is selected, and the project starts with the case top, bottom, and sides. The table saw woodworker is likely to accept one of the sawmill’s edges of each board as starting points. After flattening a face and thicknessing, that edge is jointed and the opposite edge is ripped parallel.

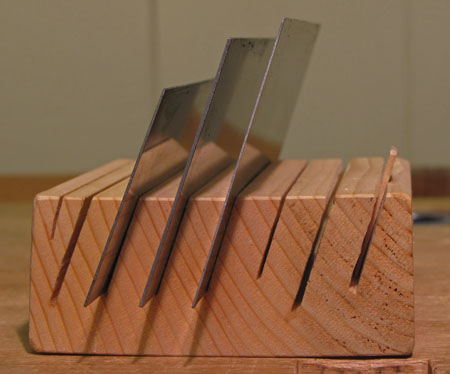

The bandsaw guy is likely to start with more design freedom and not assume that the case will have straight edges, but even for a customary case with rectangular components, he has more opportunity to sensitively make the most of the wood. One of the most common pitfalls early in a project is automatically accepting the board’s edges that were sawn at the mill. The bandsaw guy studies the board and extracts the best parts, unfettered by the original orientation of the figure.

Resawing, the bandsaw’s forte, gives the freedom to seek out and use excellent wood in any thickness. For example, matched sides could be created from a figured billet.

Well fans, it looks like the bandsaw is doing moves the table saw has never seen. Ouch.

Wait, you say, isn’t it more accurate to rip the opposite edge parallel on the table saw? Yes, and if the table saw is available, use it. However, the advantage is small, especially with a well-tuned bandsaw. Furthermore, in both cases, the most accurate and well-surfaced final rendition of fitted edges will come from a handplane.

What about crosscutting? Again, the table saw has an advantage but it is only a little more trouble, and it is more controlled, to shoot the ends by hand which can be done after they come off the bandsaw.

The bandsaw is an MMA fighter and the table saw is a classic boxer.

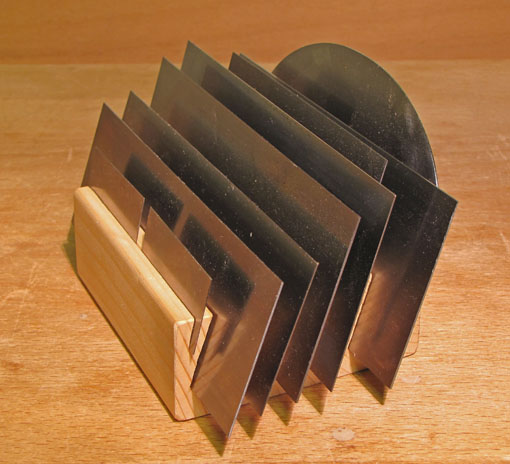

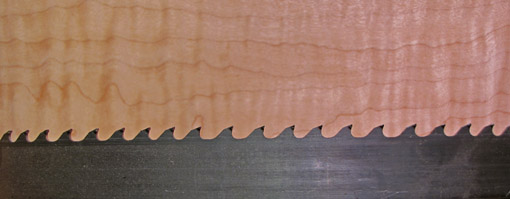

Let’s consider making the doors. This is where the fight goes to the ground. With the bandsaw you can easily resaw a beautiful boardto make bookmatched panels that will be the best feature of the piece. Yes, you can resaw with the table saw but it is awkward and limited. Resawing is a gateway technique that can change how you think about wood.

Ha, you say, making the door rails and stiles has got to be where the table saw has the advantage. Yes and no. Once again, the all-important management of the wood is best done on the bandsaw. The figure in the wood used for the frame should be harmonious. Some craftsmen even like to resaw and bookmatch these pieces. The inside edges of the frame members will come off the jointer (hand or machine), and it is handy to then rip them on the table saw. However, for fine work, the width of these pieces will be cut a bit oversize and the final fitting of the doors to the case is best produced with a hand plane. A bandsawn edge is an adequate starting point for that.

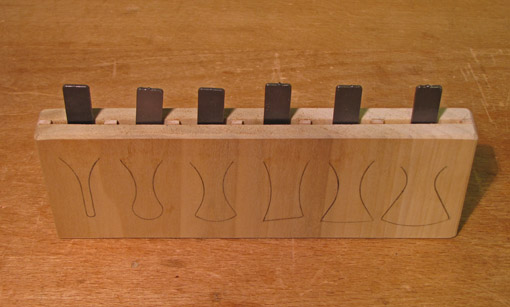

Creative, interesting handles for the doors are more likely to come from a shop with a bandsaw.

And so the table saw taps out.

The main points are that the bandsaw facilitates more creativity in design, and far more artful use of wood. Though the table saw does have advantages in ripping and crosscutting accuracy, these are easily circumvented by using the bandsaw in conjunction with hand tools in an incremental, controlled approach to fitting the parts of a project. In short, a bandsaw-centric approach can produce better craftsmanship.

Next: The Rematch. Let’s look at how this applies to making a table. Now this could get ugly.