I don’t mean to complain but . . .

1. Ulmia used to make a little vise that I’ve only seen in The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking by James Krenov, and months too late on Ebay. It is an Ulmia “Hilfs-Spannstock” (auxiliary vise) model #1812. [Note: One vise jaw is stamped “LSP-2816-4” and the other “LSP-2817-4” but I don’t think those are model numbers.] It can be clamped to the workbench top for holding small work, but, more usefully, can be secured in the tail vise to hold thin, small, and narrow parts. I have a shop-made alternative plus another option to be discussed in a future post.

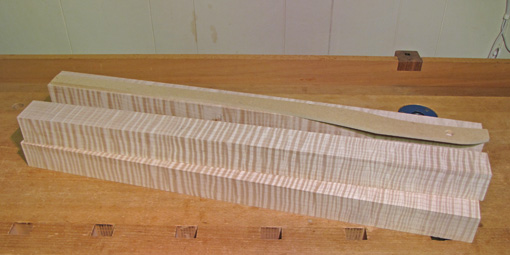

2. The Lie-Nielsen convex sole block plane gets plenty of use in my shop since almost everything I make involves multiple curves. I like the shallow 27″ radius along its length, but it would be more useful for me if the 3″ radius across its width were shallower. Thus, even better would be a few different models with different radii. The plane is very handy to use but, for my taste, could still could be a bit bigger overall, and would be easier to grasp with grooves on the sides as finger grips.

3. I wish the Lie-Nielsen #2 had an option of a 50° frog as do most of their other bench planes. I think 50° is the best basic go-to angle for bevel-down smoothing planes and would make the handy 7 1/2″-long #2 more valuable.

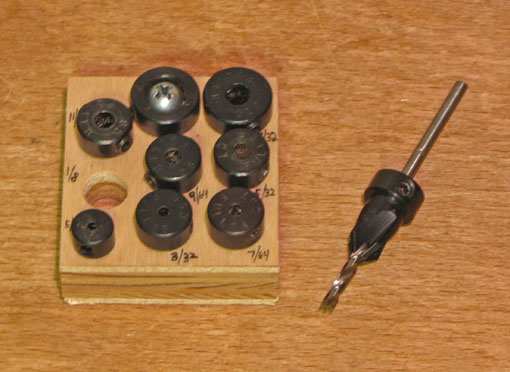

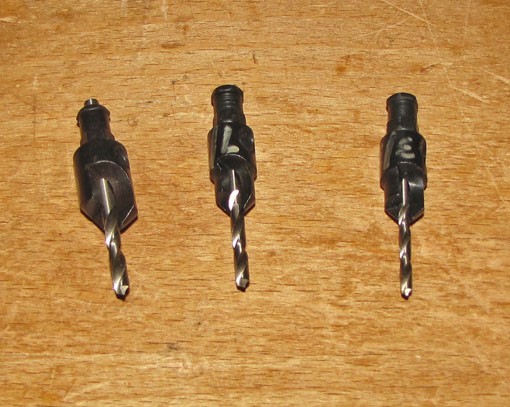

4. The rose-head countersink with radially-asymmetric flutes that Lee Valley used to make is just about perfect, but as far as I know, has disappeared from their product line.

5. Veritas (Lee Valley) makes saddle squares and other, similar, markers which are very nice except for the annoying cut-away on the inside of the angle which is supposedly to vault saw whiskers. Who has these big saw whiskers and why would you want to preserve them? The cut away causes your layout line to deviate at the corner, often just where you need it most. This type of feature is found on machinist squares to vault metal burrs but is a disadvantage on tools used for marking continuous layout lines on wood.

The above suggestions are made here with great respect for these excellent companies.

6. The old Disston “Stronghold” style file handles are unbeatable. I have a supply in different sizes but, as far as I know, they are no longer manufactured. I wonder if the patent status would permit their manufacture again by some company.

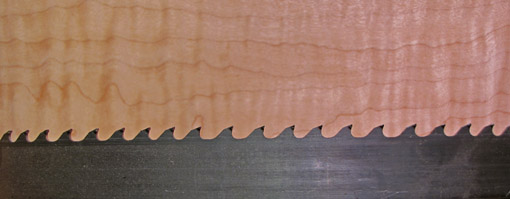

7. I don’t know about you, but my hand gets tired using a coping saw or fret saw, even of the best quality. Because the handle is parallel to the blade, one is forced to use it with a bent wrist. There ought to be some way to rig a handle which is nearly perpendicular to the blade, much like a backsaw. I suspect this would also make it a more accurate tool. Uh oh, I think I just put a bug in my ear.

8. Finally, I request a magic lantern which grants me just these three wishes: an instant sharpening system which requires no time or effort whatsoever, a board stretcher (especially for width), and, most of all, a clock that doesn’t move unless I want it to. I’ll pay for shipping, no problem.

Readers, you undoubtedly have your own lists, and if I thought about it longer, my list could certainly exceed this one. Thanks for reading.