In casework, doweling can be a good choice to join the end grain of one board to the face grain of another across their widths. This method for making cabinets was described and popularized by the late James Krenov in The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking. While noting that dowel joinery opens up many design options where the sides meet the top and bottom of a cabinet, Krenov warns us to use good judgement in selecting it for a piece; though durable, it is not for heavy-duty work.

The joinery in the pieces I have made with this method has remained tight for many years without a hint of problem. Nevertheless, some doubts have lingered in my mind about a joint that involves relatively little side grain gluing surface compared to the gold standards of mortise-and-tenon and dovetail joints. I wanted to see what was really going on inside dowel joints.

To do that, I had to make ’em and break ’em. My qualitative observations, combined with some intuition and educated guessing, are informative enough for my purposes. This is not a joint strength test, nor is it scientific. The photos show typical results.

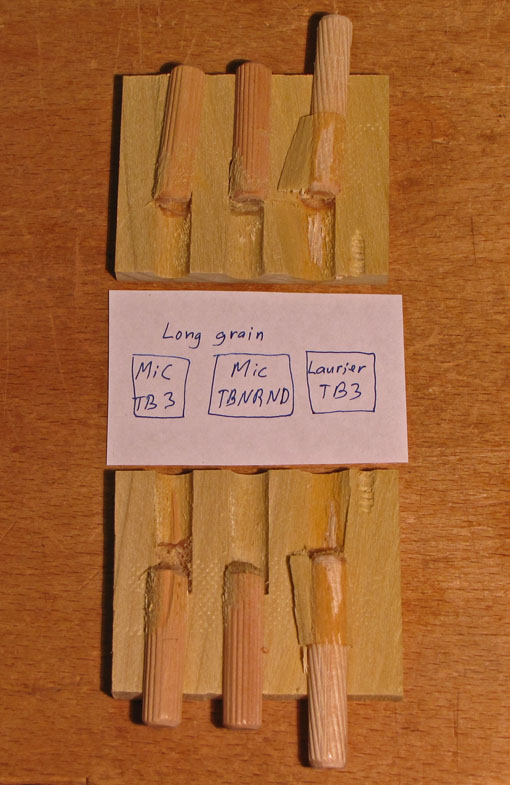

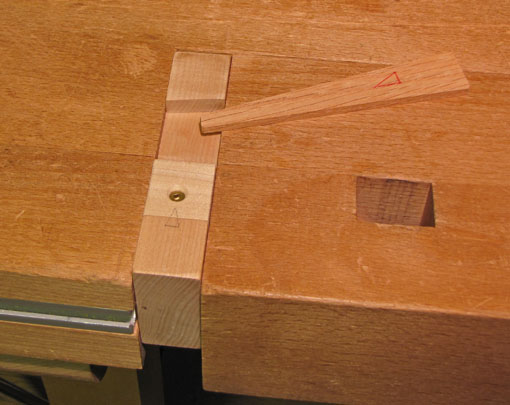

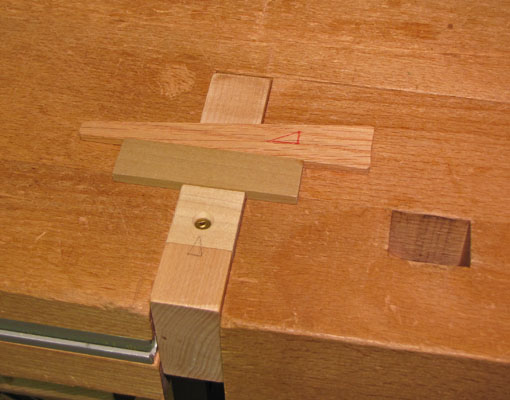

First, let’s look at the “end-grain side” of the joint where the long grain of the dowel is parallel to the long grain of the board.

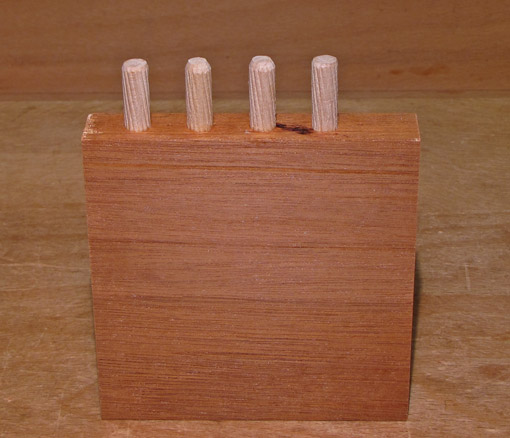

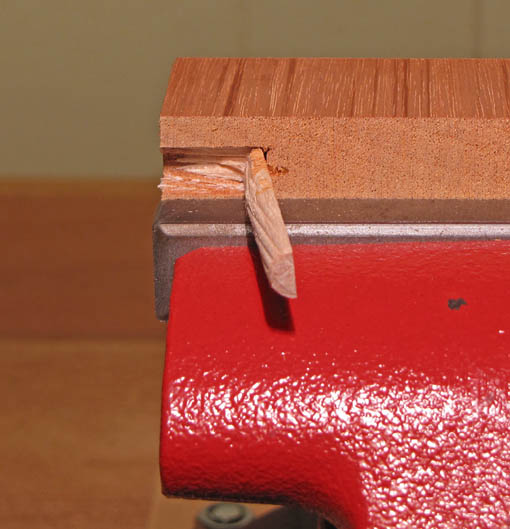

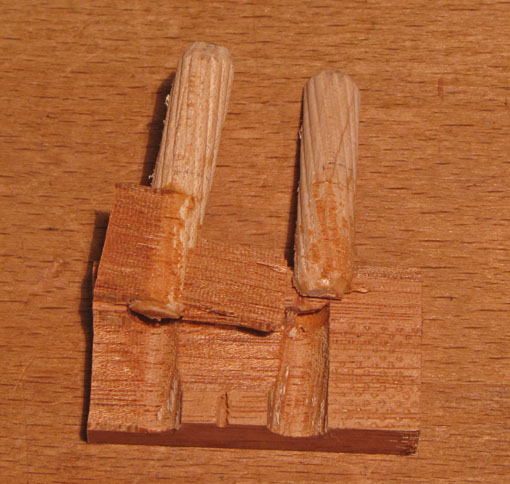

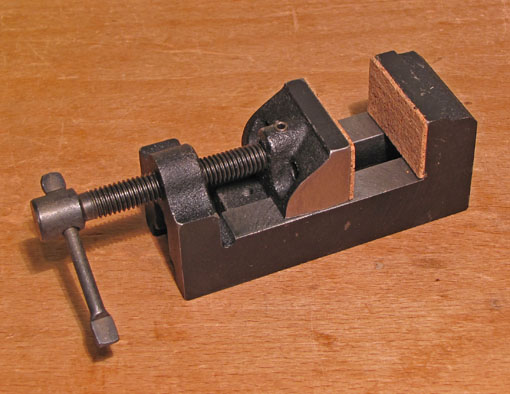

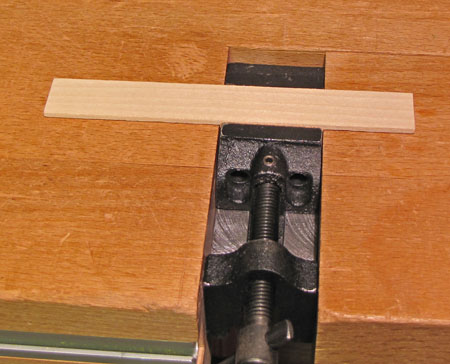

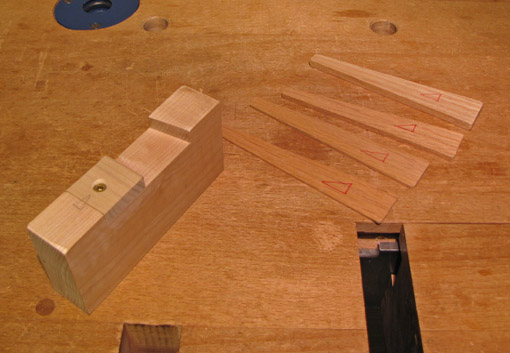

Using a DeWalt Pilot Point bit and a Krenov-style jig, 3/8″ holes were bored in poplar in the long-grain direction, deep enough to allow 3/4 inch of dowel insertion plus room for excess glue. Glue was spread only in the holes. After 24 hours, the wood was sawn through the middle of its thickness. Each half was secured in a vise, and each dowel was then hit with a hammer toward the open face to make the connection fail. The photos show the dowels snapped backwards, exposing the half hole.

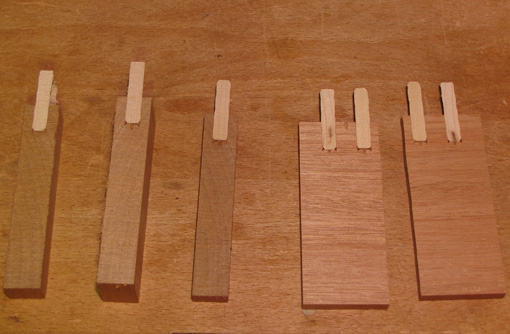

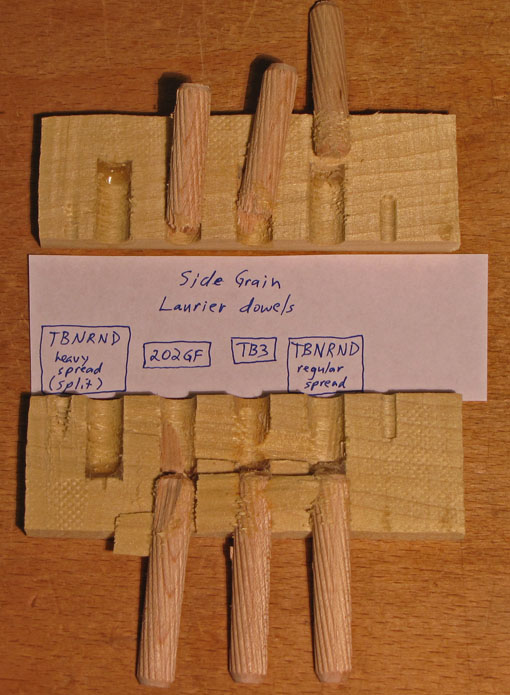

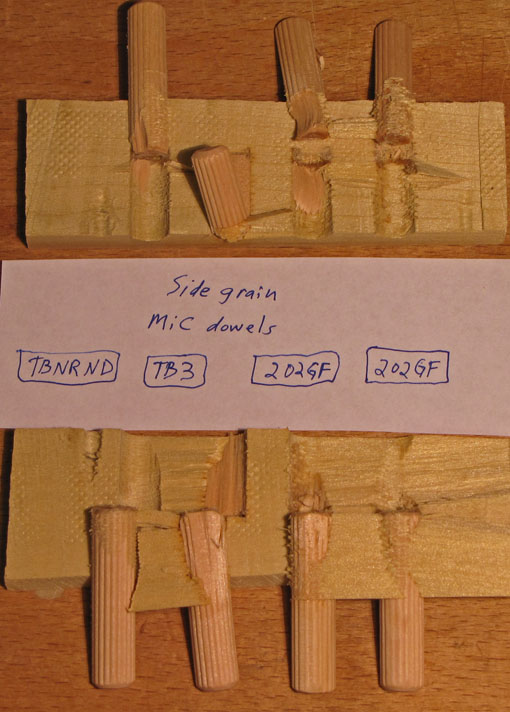

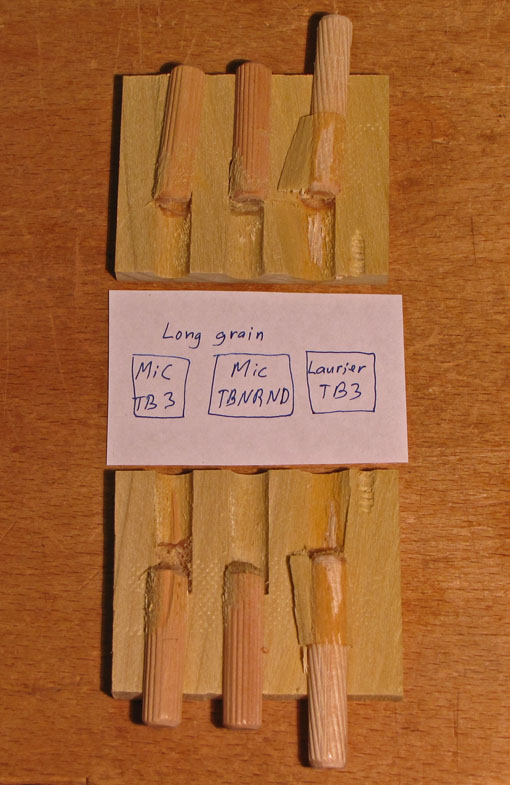

From left to right,above:

1. A made-in-China (MiC) dowel glued with Titebond III. Fair adhesion – some wood is torn away.

2. A MiC dowel glued with Titebond No-Run No-Drip glue. The bond largely failed as evidenced by the relatively clean surfaces.

3. A Laurier brand dowel, made in Canada, glued with Titebond III. Plenty of wood failure, indicating a good joint. That’s what I’m looking for.

Update Aug 29, 2017: A reader has informed me, based on information directly from Laurier, that Laurier dowels are no longer being manufactured. The owner has retired, and the machinery that makes the dowels is for sale. A few sizes remain available at justjoinery.ca

The TB No-Run No-Drip glue is very viscous, and handy in that it doesn’t run down and collect at the bottom of the hole. However, in other tests I found it did not spread well over the Laurier dowels which have less space for the glue in their spiral flutes. There was too much resistance to inserting the dowels, the glue got pushed down, and too much pressure was created. I thought it might work well with the more deeply fluted Chinese-made dowels, and they did go in easier, but TB III still made a better joint with them.

So, for long grain dowel insertion, I’ll go with Laurier dowels and Titebond III. (In other trials, Lee Valley’s 202GF performed similarly to TB III.)

Lee Valley sells the Laurier dowels. Grizzly sells the Chinese-made dowels. To keep myself out of trouble, I emphasize that these are not scientific tests, and my conclusions that I am sharing with you are for my purposes in my shop. These should be regarded as anecdotal findings. Please refer to the manufacturers’ and vendors’ literature and make your own choices.

Of course, there is the other half of the joint to consider – the face grain board. Obviously, the same dowel must be used but it does not have to be the same glue in each half. So, in the next post, we’ll look at side grain insertion of the dowels with various options. This is the part of the joint that creates more doubt for me since much of the dowel surface is bonded to end grain surfaces inside the hole. The results of my tests surprised me.