Why part 6? Parts 1-5 were posted in 2010, and cover the main Western and Japanese handsaws and joinery/backsaws that I use. I have since added the Bad Axe dovetail saw to that group and it has risen to the head of the class. This post will cover bowsaws. Part 7 will cover coping and fret saws. Part 8 will cover miscellaneous accessory saws. 18 saws isn’t a lot, right? Right.

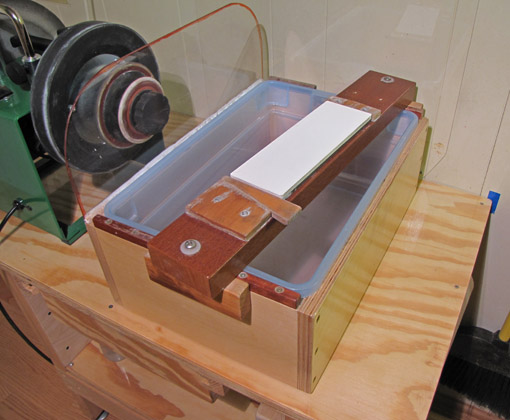

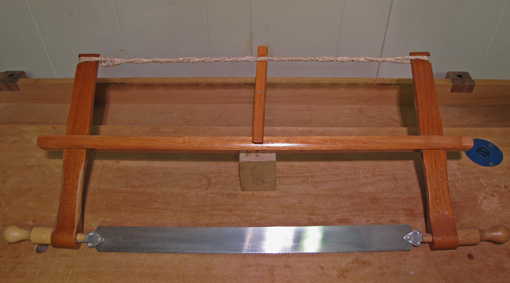

The Woodjoy bowsaw, pictured above, is my bandsaw without a motor. Glenn Livingston produces this thoughtfully designed and beautifully made saw along with other excellent tools. It is a very sturdy tool with about 16″ between the stiles. The toggle system easily permits half turns, which is important in properly setting the blade tension.

The “Turbo-Cut” blade, listed at 400mm (15 3/4″) long but with a comfortable 13 1/2″ of tooth line, has super-hard (>Rc 70) Japanese-style teeth, 15 tpi. The pattern, which could be considered a modified ikeda-me, is seven three-bevel crosscut teeth followed by a pair of special rakers that have their end bevels cut in the opposite direction from those of the crosscut teeth. It crosscuts fast, and seems to rip even faster.

The blade is about 5/16″ wide, .024″ thick, with the teeth widely set to a .048″ kerf. This makes it surprisingly maneuverable following curves, though the cut is fairly rough across the grain.

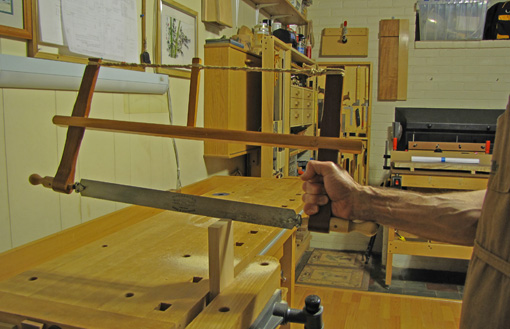

For power, comfort, and accuracy, I prefer to use this saw with a horizontal push cut, and the frame is plenty rigid enough for that. Some may prefer a horizontal pull cut, or a vertical push cut, though the latter may be difficult at typical workbench height.

This is a fairly heavy saw, so here is how I hold it for cutting curves. I grip the handle with my dominant right hand, similar to holding a straight-handle dovetail saw, and align it with my right shoulder. This reliably steers the saw while my left hand provides passive support near the end of the rail. The saw works best when you let it do the work and use as much of the blade length as you can with every stroke.

This saw could quite reasonably be used in a hand-tool-only shop in place of a bandsaw for roughing out curved table legs and other heavy curved work. It has the moxie and the control to easily handle 8/4 maple.

I like this size saw for curved work. Woodjoy also makes larger sizes, and Turbo-Cut blades are also available in 1 1/4″ width.

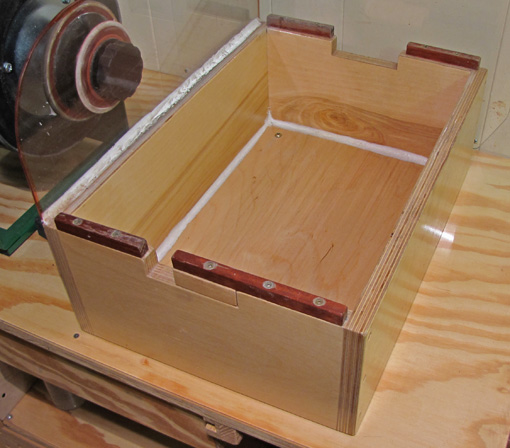

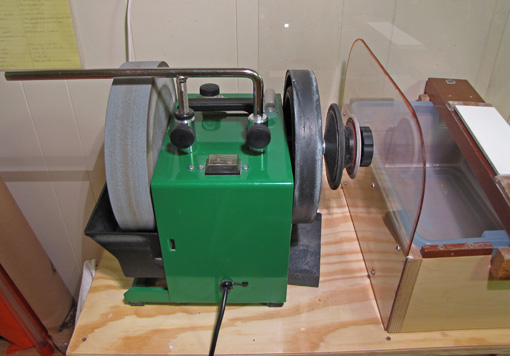

I bought the bowsaw pictured below more than 30 years ago. It was made in Denmark by JPBO but, as far as I know, is no longer available. This is the model of saw that was preferred by the late great teacher Tage Frid. He used it with a horizontal push stroke for joinery and crosscutting, and vertically for ripping stock.

Not long after buying it, I replaced the original blade with one labeled “The K and P Saw, Western Germany,” also no longer available. An excellent blade, it is tapered in thickness from the teeth to the back, so it can be prepared with very little set. The blade is about 19″ long and has 10 tpi, which I file rip. Frid advocated a rip filing for both ripping and crosscutting.

This saw is surprisingly light yet rigid, probably due to the width and orientation of the frame members – unlike most bowsaws, the wide dimension of the rail is horizontal. The toggle system is less refined than on the Woodjoy saw, but half turns are still possible by loosening and reinserting the toggle stick in the opposite direction, then retightening it.

I find I get the best control and endurance by holding it by the lower part of the fairly wide stile.

This saw does not get a lot of use in my shop now but it is still handy to have for various ripping tasks. I find it is especially accurate and comfortable for cutting tenons, though I’m in the habit of using the ryoba for that.

Because I like using my bandsaw so much (“the hand tool with a motor“), I also don’t frequently use the Woodjoy bowsaw. Nonetheless, I still want both of these hand tools in my shop – they give me options and they’re ready when I want them.

Next: the fret saw and the humble coping saw.