What are the best hand tool and the best power tool in your shop? Just considering this question will give you pause to ponder what really makes a tool great. The answers will help guide you in what tools to buy and what tools to employ in a project.

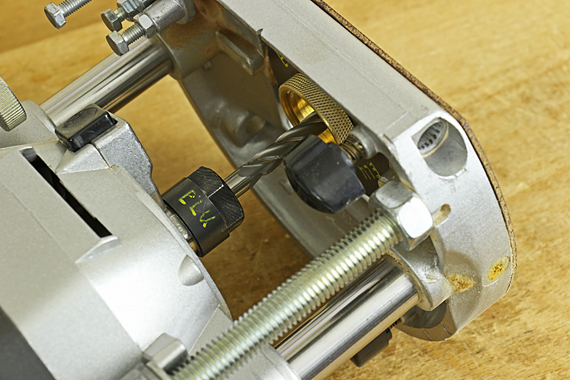

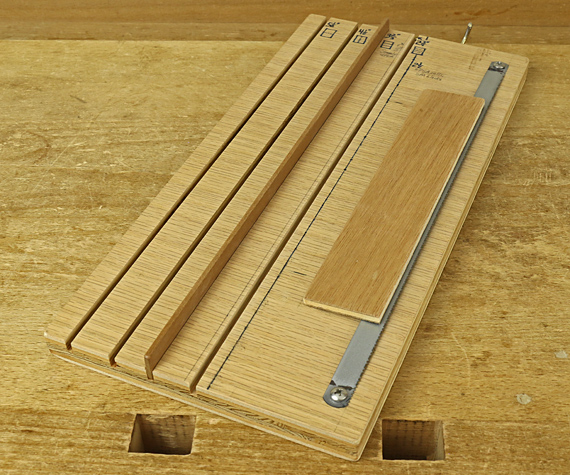

For me, the best hand tools in my shop are my full set of blue steel “suminagashi” (or “mokume”) Japanese bench chisels made by Teiichirou (Teijiro) Okukbo in Yoita, Niigata, Japan under the brand name Daitei. A few are pictured above.

I suppose it is possible (e.g. Tasai) but it is hard to imagine a better chisel than these. They can be made hair-popping sharp, they are the easiest tools to sharpen that I own, and the durability of the edges is astounding. The ergonomics are just right for me, and their beauty is inspiring. “Eleven” stars.

Other candidates were: my Bad Axe backsaws and Lie-Nielsen #4 and #7 planes. These are full of intelligent, functional features and the accuracy parameters are excellent. Honorable mentions: Starrett straightedges because of their core accuracy that forms the basis for accuracy in the whole shop.

A sports team coach knows that when a job needs to get done in crunch time, he’ll go to his best athlete. That player has the composition, inherent abilities, and playing smarts to find a way to get the job done, often in a manner no one expects.

Similarly, a good woodworking tool must start with a great design, usually time-proven but allowing for smart innovation. Then, the execution must be top quality. You do not want a tool that contains frustrating design or construction flaws for which you must constantly compensate.

With that great tool in hand, your confidence is uplifted. You find ways to get things done well that you maybe did not even expect. The bottom line: that tool helps you become a better craftsman. When at all possible, those are the tools to buy and put to work.

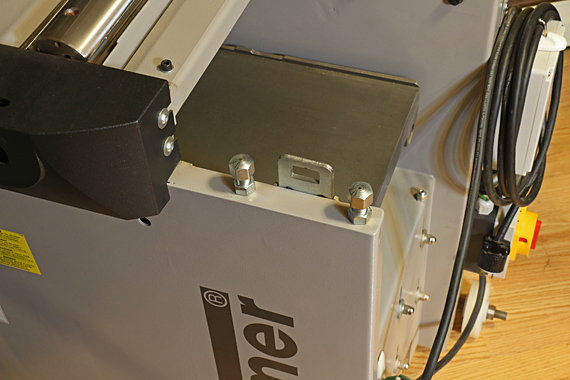

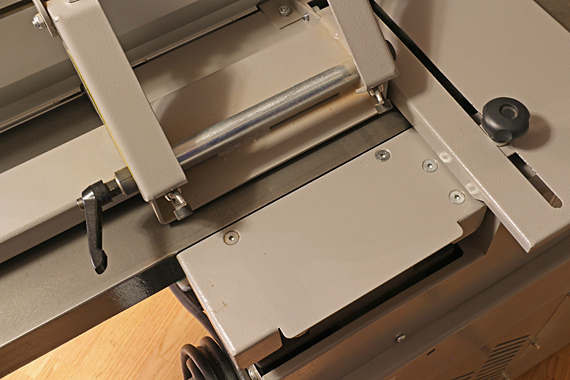

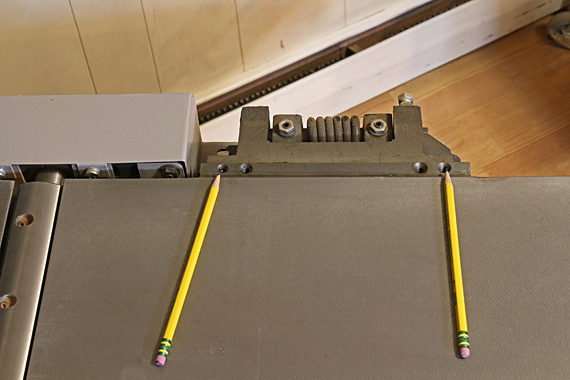

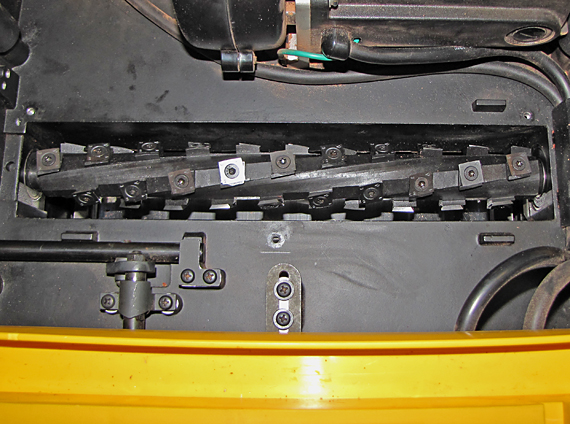

So, the best power tool in my shop is the Byrd Shelix carbide spiral cutterhead that I installed in my DW735 thickness planer. The design is about perfect. The rows of cutters are in a true spiral (helix) pattern, and each cutting edge is cambered. Each cutter can be reset or replaced to make use of its four edges. Along with the outstanding qualities of the DW735, the Shelix allows me options in stock preparation that no conventional cutterhead comes close to matching.

Just like a coach, these great tools allow me to form a better game plan, execute it well, and very often go beyond what I could otherwise do. These tools do not drag me down, and do not need to be questioned and compensated for. I become a better craftsman and I do better work.

That is the test of a great tool. I suggest keep this in mind the next time you open a tool catalog or visit your favorite drool tool store.