Commenting on a recent post, a reader asked:

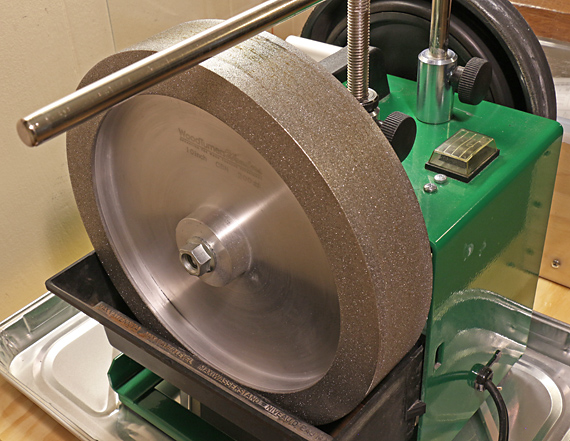

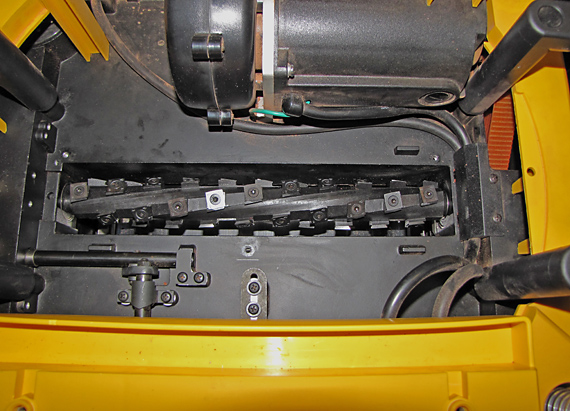

Do you typically use your DeWalt 735 for planing, and your Hammer A3-31 for jointing? I am starting to look at combo jointer-planer units, and would be interested in knowing if you typically use separate machines for these two functions. You mentioned in a previous article you have a Byrd Shelix cutterhead on the DeWalt and straight knives on the A3-31.

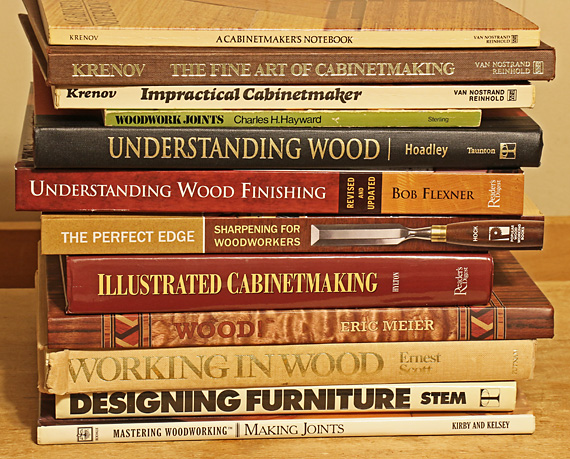

My reply follows-up on, and reinforces the large amount of material on this blog regarding jointer-planer combo machines, the Hammer A3-31 in particular, the Byrd Shelix spiral cutterhead on the DW735, and options for the first machine a woodworker should buy. Thanks for asking!

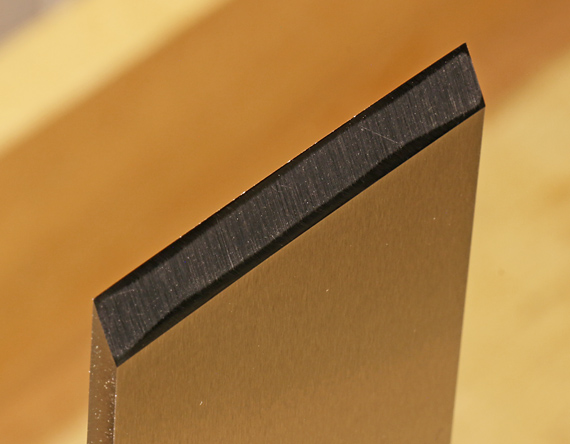

The big factor is the wood. For easy-going boards – tame species, not rowed, no curl/blister/birds eye, etc. – I will usually go ahead with the thicknessing on the A3-31 because it is already up and running, and I know the results will be good. For figured wood, I will definitely go to the Shelix because it performs magnificently for that. For very hard or abrasive species, even without figure, I prefer the Shelix to save wear on the straight blades in the A3-31.

A couple of other factors also come into play. The DW735 has a longer snipe than the A3-31, though the depth of both is very small. Snipe can be avoided altogether with continuous feeding, but that can be awkward in a one-person shop.

Also, a tiny bit of thickness cannot be removed well on the final pass with big planers because the impressions created by the metal pawls will often not be entirely removed by the shallow depth of cut. Sometimes I do want to remove just a very small amount such as for matching another piece that I’ve messed up. I can remove as little as I want on the final pass with the 735 because the rubber rollers do not create impressions (assuming they are reasonably clean).

As for width, the A3-31 cuts 31cm wide (hence its name), about 12.2 inches. I want every bit of that. A wide jointer is a wonderful thing in the shop!

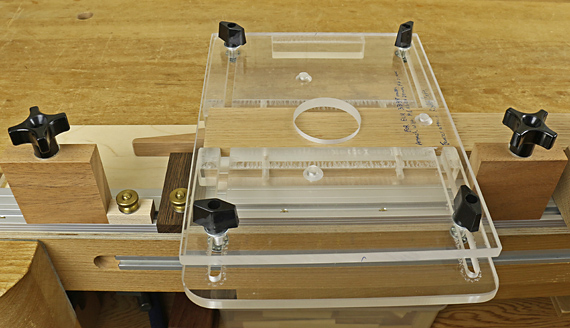

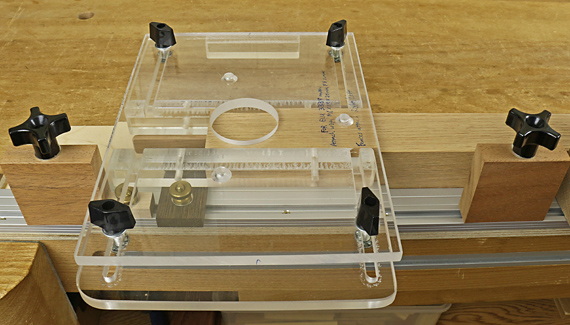

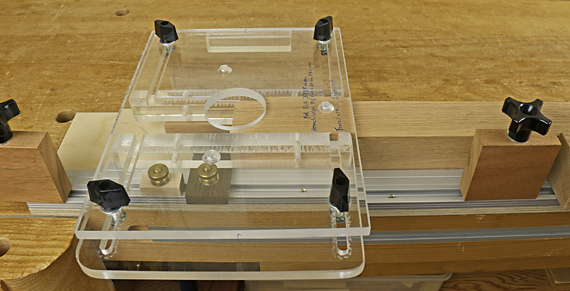

I installed the Shelix in the DW735 about one year before I bought the A3-31. Then I did not want to spend the extra money for a second segmented spiral cutterhead, this time on the A3-31. I expected to use the 735 with the Shelix for almost all of my thicknessing, but in time I have come to use the A3-31 with its straight blades for plenty of my thicknessing too.

I think for most of us, shop equipment evolves with our resources rather than follows a master plan. I am content with my current setup. However, if I were to start fresh and buy one machine, it would be an A3-31 with their “Silent Power” spiral cutterhead.

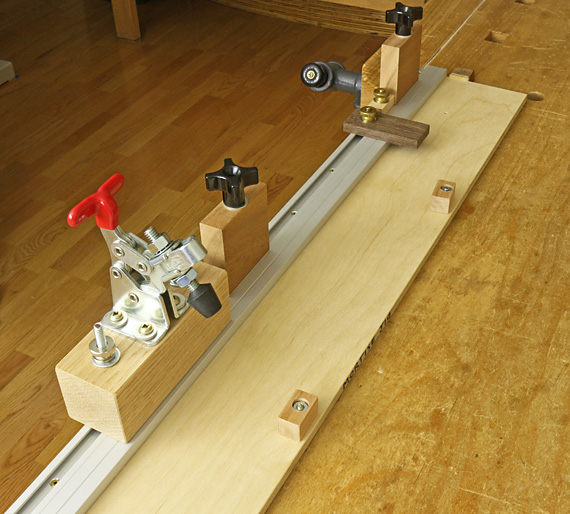

For an option that is less expensive than a big jointer-planer combination machine, but is still highly versatile, start with a good portable thickness planer as your first machine in the shop. I still recommend the DW735. Then apply the following process:

Jackplane and/or scrub plane a rough surface on one side of a board. It should have no cup, twist, bow, or flex. It will not be pretty, but it only needs to register on the planer bed. Draw pencil lines every few inches across the opposite side of the board, including close to the ends.

Send the board through the planer with the worked side down on the bed. Take the passes necessary to remove the pencil lines, indicating that the blades have touched all of that surface. Then, flip the board and clean up the side that you worked with the hand plane. Then joint an edge by hand, rip to width, and clean up with a hand plane.

I do not recommend a 6-inch jointer as a fundamental tool for a serious furniture maker. It is limiting from the start and will very likely be obsolete later. On the other hand, wouldn’t it be nice to have a 16-inch Felder jointer-planer with a spiral cutterhead? Yes, yes it would.