• Friday, December 01st, 2017

If you enjoy and find useful the material here on the Heartwood blog, here are some offerings by your devoted keyboard warrior that I think you’ll also like. As with all my woodworking writing, it comes from the “sawdust and shavings of my shop.” No armchair pretensions, I write what I do. I hope these materials are helpful for your woodworking.

Popular Woodworking: August 2017 (#233) “Shapely Legs”

This article ties together techniques discussed on the blog to create a practical system for designing and making curved legs. This is how you go beyond copying plans laid out on grids of 1-inch squares in books and magazines. The idea is to empower you to create your own designs. I cover wood selection, transferring curves from a drawing to make a template, marking out and sawing the wood, and tools and skills for refining the curves after sawing.

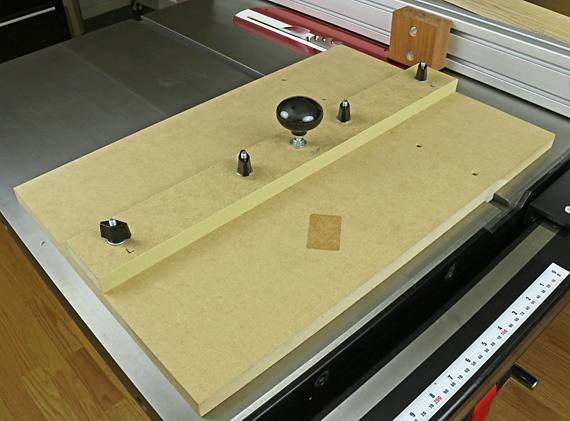

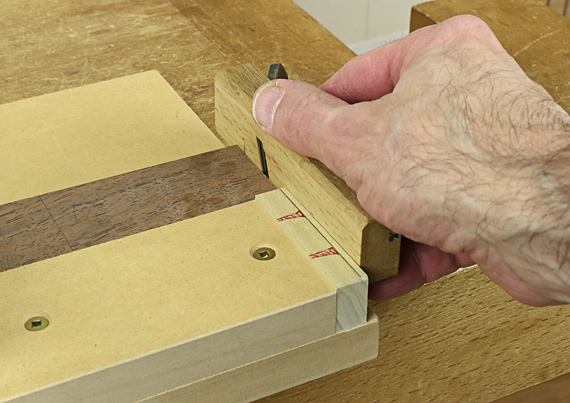

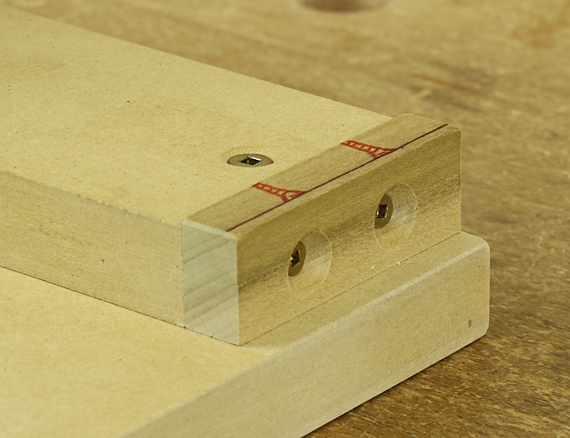

Furniture and Cabinetmaking: July, August, and October 2017 (#259, 260, and 262) “Edge-to-edge Joinery,” parts 1, 2, and 3

This three-part series with more than 6,000 words and three dozen photos explores the techniques, rationales, and controversies of the ubiquitous edge joint. I truly think it is as complete and thoughtful a discussion of the topic as you will find anywhere. F&C is most readily accessible at a reasonable price in electronic form from Pocketmags.

Furniture and Cabinetmaking: February 2017 (#254) “Jointer Tune-up”

This article is reproduced from material on the blog. It is a logical and doable approach to tuning a machine that can otherwise cause a lot of frustration.

Fine Woodworking Workshop Solutions: Winter 2017 “Making Better Use of Your Space” – Smart floor plans for workshops of all sizes.

Written by Fine Woodworking editors, this article has two pages of photos and text showing my humble 11×17-foot slice of heaven as an example of a small shop design, while the rest of the article shows an example of a medium and a large shop. The article has a nice plan diagrams of the shops, and shows some of the setup tricks and systems. The article appeared earlier in Fine Woodworking’s Tools and Shops annual issue, Winter 2014, with the cover declaring “dream shops, small and large,” so, wow, I’m living the dream, I guess.

Wood magazine:

October 2016 (#242) “It’s Always Something”

October 2017 (#249) “Search and Research”

These two articles are reworked from the blog, and nicely produced by the editors at Wood.

Popular Woodworking:

October 2016 (#227) “Super Nova Magnetic Lathe Lamp”

December 2017 (#236) “SensGard Ear Chamber Hearing Protection”

These are reviews of two outstanding products.

The theme that runs through these writings and the blog is that I want to inspire you and help you to build things, and experience the joy of it as I do.