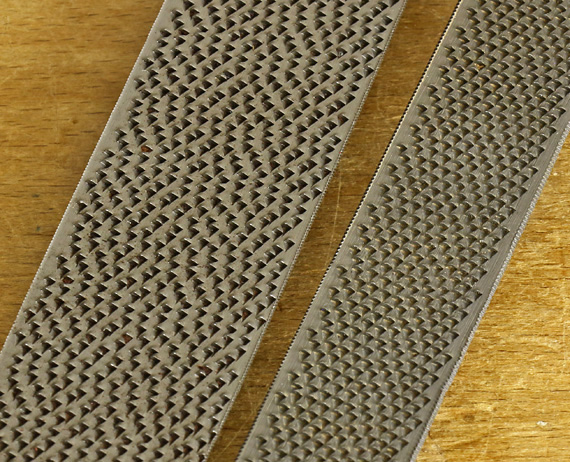

Another thoughtful refinement from Veritas, this adjuster advances the blade in smaller increments than their standard adjusters. It’s a hit.

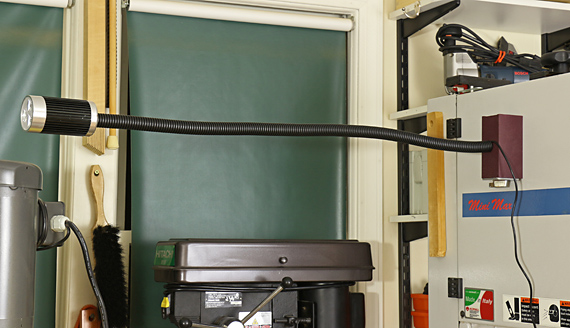

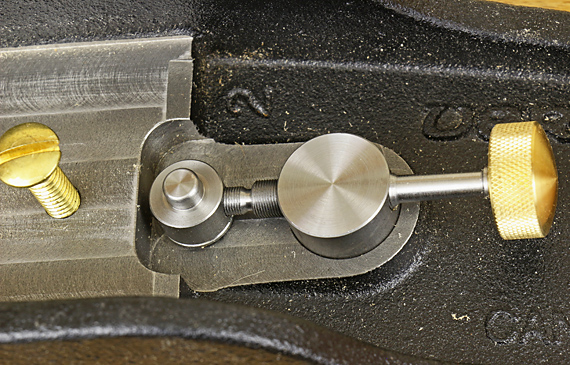

Veritas bevel-up (BU) planes use a Norris-style adjustment system, which means that one adjuster controls both blade depth and lateral alignment. In a lesser quality tool, this system could be balky but the design and execution by Veritas makes theirs function very smoothly.

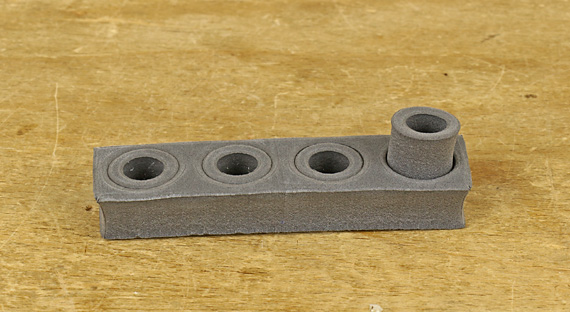

Now, just for fun, the lead screw of the slow adjuster has 58 threads per inch by my count, which translates to .0172″ of linear blade advancement per turn of the knob. The increase in depth of cut produced per unit of linear advancement of the blade is represented by the sine of the blade’s bed angle, 12° in this case.

.0172″ x sin12° = .0172″ x .2079 = .0036″ depth of cut increase per one turn of knob

This works out to .0009″ or about 1 thou change in shaving thickness per quarter turn of the knob.

This may sound like too tentative an approach but in practice this exceptionally smooth mechanism is not only precise but also pleasant to use. I am usually using the BU smoother for difficult wood where small differences in cutting depth really matter. I suggest Lee Valley use the slow adjuster as standard in their BU smoothing planes, or at least offer it as an initial option.

The Veritas bevel-up jack plane, on the other hand, is used for tasks that require less precision in the cutting depth, so there I prefer the original, quicker adjuster.

With the Norris adjuster, side set screws that control the blade registration near the mouth, lack of a chipbreaker, and an easily adjustable mouth opening, you can practically set up a Veritas bevel-up plane with your eyes closed.

Just as a reminder, if the handle and knob on my BU smoother do not look like the Veritas versions, it is because they are not. They are wonderful retrofits made by Bill Rittner of Hardware City Tools.