In the previous post, I discussed how a 20-22° bed in a bevel-up smoothing plane can produce a wider range of useful attack angles without resorting to excessively high sharpening angles. The use of narrower sharpening angles has, in turn, several advantages:

1. Sharpening is easier. It is simply more difficult to get a good, sharp edge at, for example, 43° than 33°. It is also awkward to work at the higher angles, and the feedback from the surface of the stone is not as good. I think this is readily evident but some may disagree.

2. Based on my experience, and I think most woodworkers would agree, a blade with a very steep secondary bevel dulls faster than one with a more usual, narrower bevel, all else being equal.

—————————–

Sidebar: how an edge dulls

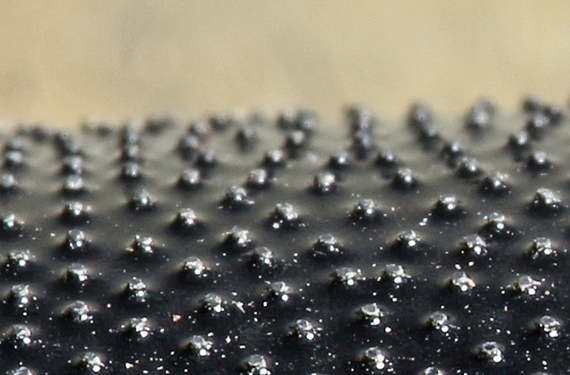

The profile of the sharp edge of the blade ideally starts out as two straight surfaces meeting at a clean, sharp point. As the edge wears, steel is abraded away from the surfaces near the edge, and the original point becomes rounded over. The worn surfaces of the blade that approach the blunted edge can be thought of as “wear bevels.” Thanks to Brent Beach and Steve Elliot for their development and detailed study of these concepts.

For both bevel-up and bevel-down planes, the wear bevel on the top side of the blade (the side facing away from the wood) is wider than that on the bottom side, because it is the top (front) of the blade that bears the brunt of the collision with the wood. The bottom-side wear bevel, which is on the flat side of the blade in a BU plane, is nonetheless important.

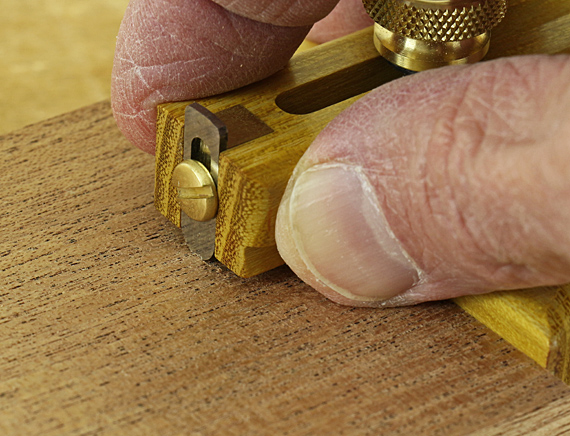

Brent Beach explains the value of removing the lower wear bevel when sharpening to regain a truly sharp edge, to maintain proper clearance of the blade edge from the wood, and to avoid the need to apply undue pressure when planing. David Charlesworth’s Ruler Trick is thus particularly helpful for bevel-up plane blades.

——————————-

3. A functionally sharp edge is preserved longer when the blade is sharpened at a narrower angle. This is consistent with point #2. Australian planemaker Terry Gordon explains this nicely in a recent article in Furniture and Cabinetmaking magazine (November 2018, Issue 276, pp. 48-50). It is best understood diagrammatically but the gist is that a skinnier edge retains useful sharpness longer by remaining narrow longer.

In summary, there are important advantages in sharpening and edge endurance when using the narrower sharpening angles permitted by a higher bed angle in bevel-up smoothing planes.

For example, if you want a 55° attack in your BU smoother, you’re better off being able to sharpen at 33° with a 22° bed (=55°) than having to sharpen at 43° with the 12° bed (=55°) in currently offered stock planes.

Coming up: still more issues. Can you tell that I’m building a case that I think L-N and L-V should hear?