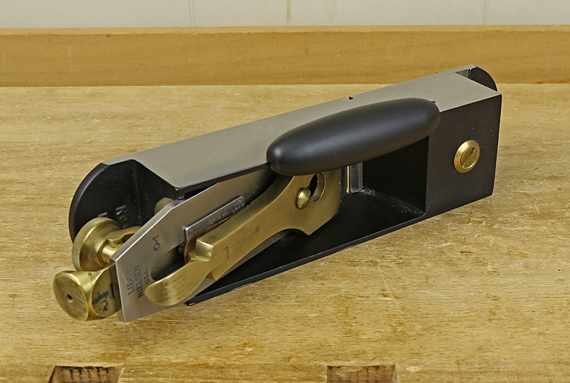

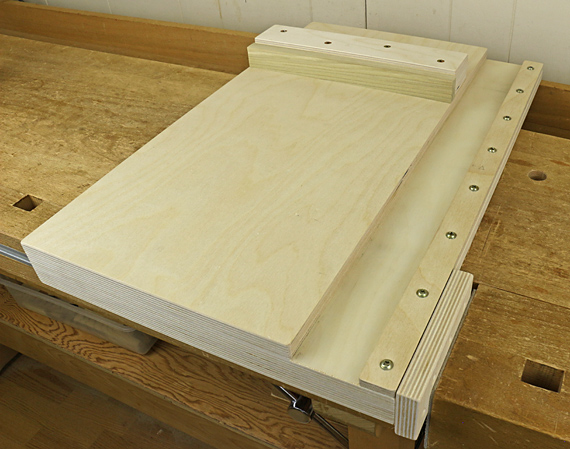

Here are the details of the shooting board I use. It is designed for use with the Veritas shooting plane, as well as to fit my workbench, the work I typically do, and my personal physical characteristics (I’m right handed).

It is constructed primarily from 18mm 13-ply birch plywood. The base and thus the overall dimensions are 22 3/4″ x 14 1/2″. The platform upon which the workpiece rests is 11 1/4″ wide, and is glued and screwed to the base.

The right side of the platform was planed accurately straight before installation. The tiny rabbet, which is the basis for how a shooting board works, is created with the first few passes of the plane that “break it in.”

The cleat at the front, glued and screwed, hooks onto the front of the workbench. The cleat on the right side fits into the tail vise. Together, they give the shooting board rock-solid stability in all directions while in use.

The channel for the plane is about 2 1/8″ wide, and lined on the bottom with 3/64″ PSA UHMW plastic. The 9mm 7-ply birch strip, 1 7/32″ wide, on the right side of the channel is adjusted to create a snug fit for the Veritas shooting plane, and firmly secured with pan-head screws placed at 3″ intervals. It is not glued, so it can be adjusted if needed. The inside wall of the strip is waxed.

The fence block is 2 1/4″ wide, made from two glued layers of the 18mm plywood. It is glued and screwed square to the sole of the plane nestled in the channel. The 3/4″-thick (or 7/8″) poplar replaceable subfence is attached with two 3″ x 1/4″ lag screws that enter from the back of the fence block, accompanied by heavy washers. The pass-through holes in the fence block for the lag screws are actually small slots that allow for some lateral adjustment of the subfence. You may want to use a third lag screw to ensure the subfence is snug against the fence block.

There are three ways to tune the 90° angle of the subfence. You can use whatever suits you; that is a big advantage of this design. Remember, we are using the in-place sole of the plane as a reference, not the channel edge itself.

First, when you create the subfence itself, you can easily plane it as needed – it’s friendly poplar. Then, when you attach the fence you have the chance to put very thin shim(s) between it and the fence block. Now, if you placed the fence block dead on and use a perfectly thicknessed subfence, you should not need to do this, but it is good to have the option! Finally, when in use, you can put a piece of tape or a shaving between the workpiece and the subfence to fine tune the working angle.

For angles other than 90°, you can make and attach a different subfence.

The front of the subfence is 7 3/8″ from the back edge of the shooting board. This gives more than enough length to fully support the 5 1/2″ toe of the Veritas shooting plane. I prefer the plane to have full registration against the channel edge all the way through the cut. There are many shooting board designs with the fence at the end, which causes the plane to lose full registration before the cut is completed.

Also, the 7 3/8″ works out to make the front of the fence not too far away from me, so I don’t have to lean forward too much, while still allowing the base of the shooting board to reach across the tool trough to get full support from the rear wall of the trough. This also results in enough platform depth to accommodate the vast majority of workpiece widths that I use.

The 11 1/4″ fence is long enough to firmly register almost all the work I do. You may want to make your shooting board wider. For any board longer than 20″ or so, I stack a couple of pieces of plywood under the left side of it to prevent it from tipping up at the working end.

The screw eye allows you to store the shooting board on the shop wall, away from abuse.

Remember:

- sharp!

- dynamic stability in use

- low-tech micro-adjustment

- and . . . the grippy glove on the left hand

I put a lot of forethought into this design, gathering ideas from many other designs. It has worked out very well for me. I hope it helps you with your work.

Addendum:

A plane such as the Lie-Nielsen #9 or a bench plane on its side can be gripped directly above and just behind the cutting edge. For these planes, a snug enclosed channel in the shooting board, such as shown here, is still very helpful but not essential. For the Veritas (or Lie-Nielsen) shooting plane where the grip is far behind the cutting edge, a snug channel is, in my opinion, a practical necessity. The grip location in these planes makes it too easy to get off track in the shooting stroke. Both systems work but I have come to prefer what I have detailed here for you.