If you’ve read the two previous posts on this topic, you might think that I’ve thus settled contentedly into scraping plane heaven. Not quite, there is one more thing.

The scraping plane is generally thought of as a finishing tool, analogous to a smoothing plane, suited for difficult, figured, dense woods that are prone to dreaded tearout. However, there are times when I use the scraping plane one step prior to finishing the surface. I will explain.

Like most woodworkers, I dimension almost all my wood by machine. With figured woods, shallow tearout often remains despite using good technique and well-tuned machinery. One method to get rid of this shallow tearout would be to first use the jack plane cross grain, possibly initially with a toothed blade, then go to the scraping plane.

Now I’ve got another option that is on a finer scale. I have prepared one of my Hock scraping plane blades with what I will call “microtoothing.” This toothed blade is not quite like those that are commercially available and often used to prepare a substrate for hammer veneering. I abrade, lengthwise, the unbeveled side of a 0.094″ thick Hock blade using a coarse file and very coarse abrasive paper, then make very shallow cuts with a fine saw file, about 20 or more per inch. I then file and medium hone the 45̊ bevel and burnish as usual at 15̊.

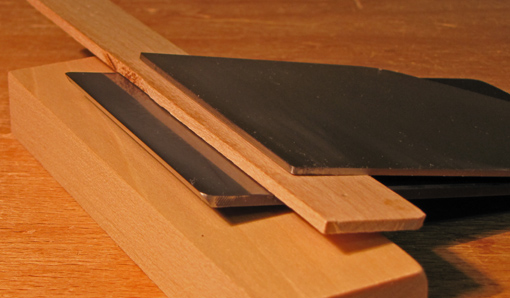

The photo below shows the microtoothed blade below a conventionally prepared blade.

The result is not a dull scraper. It is sharp, but has “microteeth.” It does not produce dust, as would a dull scraper blade, but rather shavings that resemble ultra thin cheese shreddings. (See photo at top.) The fine or coarse serrations split the shavings at every depth of cut. The huge advantage is the extremely smooth cutting action. There’s never a hang-up, slice, or chatter. The plane can be worked back and forth on the wood with abandon. The very shallow ridges that remain on the wood are quickly dispensed with by a conventionally prepared blade in the scraping plane.

This has been a very effective way to reliably remove shallow tearout with the scraping plane in the worst of woods. I use it when the jack plane procedure would be too much, but going to a clean, conventionally sharpened scraping plane blade would take too many fastidious passes. It has even allowed me to do away with thoughts of purchasing a drum sander.