It is handy to have an arsenal to scrape contours and details. This is mostly clean-up work done after routing or planing.

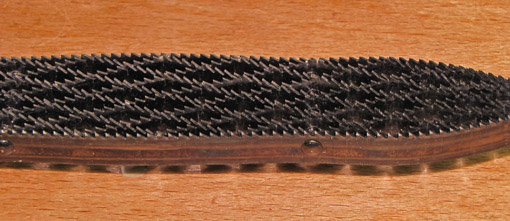

The “gooseneck” scraper, above, handles a lot of concave contours. This Eberle model is about 0.028 inches thick. I do not know the Rc hardness but it seems softer than the Rc 48-52 of my other scrapers. Lee Valley has nice choices.

Cleaning up a cove, on a raised panel, for example, can be done by setting this scraper into the cove and then angling it to make the edge match the contour. To understand this, hold a coin in front of you and observe how the visible curve at the bottom changes as you turn the coin on the vertical axis. Angling the scraper also facilitates a smooth cut, though too great an angle will cause the edge to slice the wood and create tracks.

By the way, does that scraper look like a goose neck to you? To me it looks more like a whale or maybe a goose body without its legs and head.

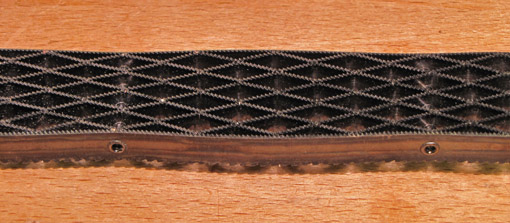

The two little guys below are handy for all sorts of clean ups such as scraping glue out of a corner. They are 1″ x 2″, 0.020″ thick, Rc 48-52, and available from Lee Valley. Because their small size makes them hard to bend, you might want to file a slight camber in one or two of the edges to avoid gouging by the corners when doing work on an open surface.

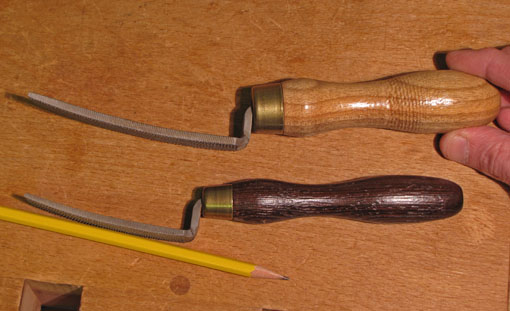

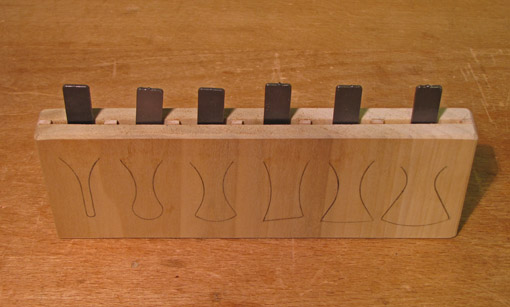

The set of Flexcut scrapers, below, are earning their place in the shop. The scrapers are inserted into the handle and secured without screws or hassle. At 0.050″ thick, they are quite stiff. The handle can be held in various ways – like a pencil, in a fist-grip, or a fist-grip with the thumb behind the scraper. Both the ends and the long side edges are useful. I don’t use this tool frequently but its versatility sure is handy when the need arises.

Lynx makes a set of contour-edged scrapers that looks like a good option, but I have not tried them.

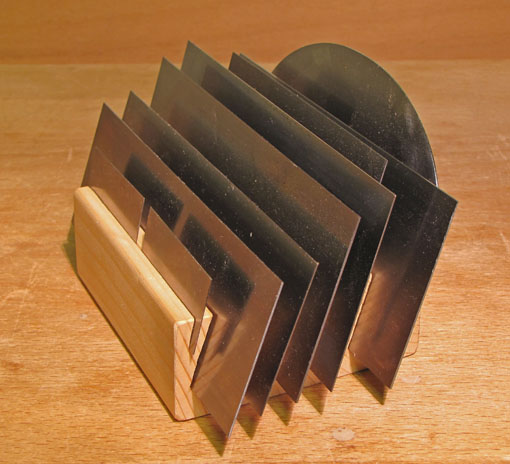

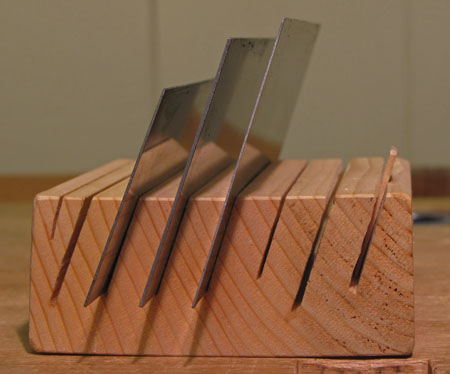

Here are the Flexcuts tucked away in the little holder I made for them.

Sharpening these small and curved scrapers can be awkward. The small scrapers do not necessarily need a burr but I find they work better with it. The short carbide burnisher, available from Lee Valley, is convenient for preparing these scrapers.

Once again, my purpose here is to present a range of options and discuss what has worked for me, with the hope that this will help you sort out what is useful in your shop where you are the supreme commander, king, lord, and unquestioned deity, unless of course, your spouse or pet happens by.