First, the tips:

The cutoffs from thick curved cuts on the bandsaw will probably prove useful, so think twice before trashing them. With a little cleaning up, they can become clamp blocks, sanding blocks, or supports under the work pieces for hand tool work.

Camellia oil oxidizes very little but enough to make it somewhat gummy after a long time in a tool oiler or on the surface of infrequently used tools. Since adding a generous amount of vitamin E oil, an antioxidant, to my storage bottle of camellia oil, the problem has been all but eliminated.

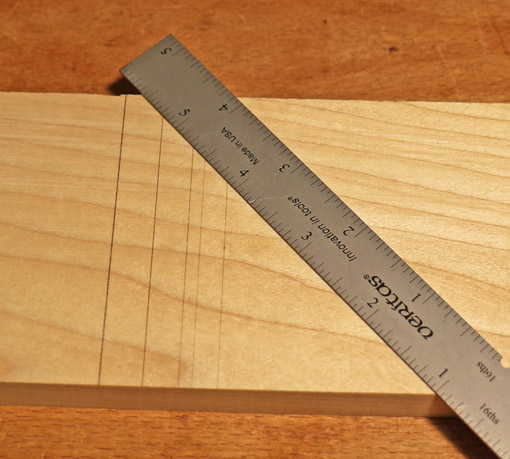

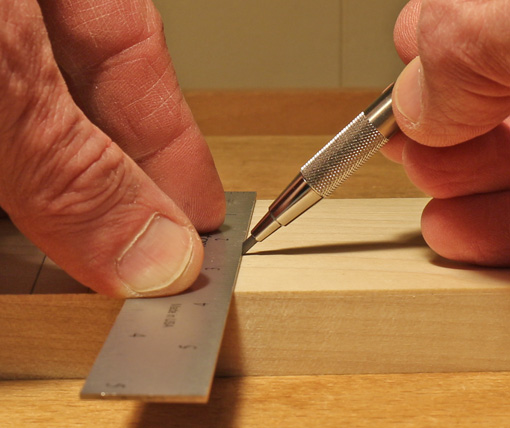

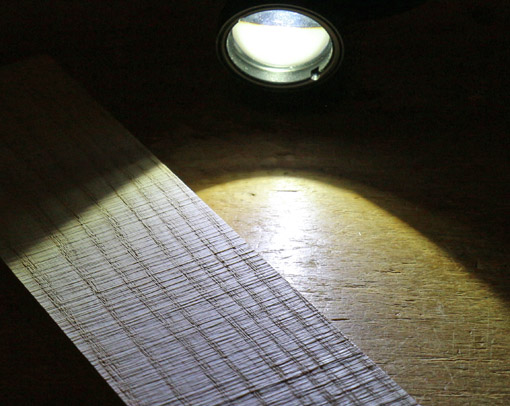

After just a few weeks, the magnetic-mount LED work light from Lee Valley has become a shop favorite. I always use it for bandsaw work where the powerful magnet keeps it stable while the 18″ flexible neck stays put. At the workbench, it is easily set up for joinery work by using the mounting plate with the 3/4″ post in a dog hole. It is also invaluable for creating a low raking light for surface finishing tasks.

[Addendum: Over time I have found this lamp to be unreliable. High quality batteries seem to drain unusually fast and leaked in the original lamp and again in a replacement lamp. I no longer recommend it.]

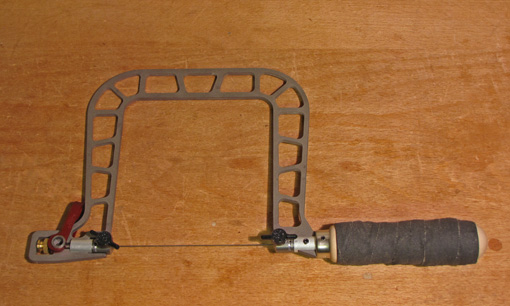

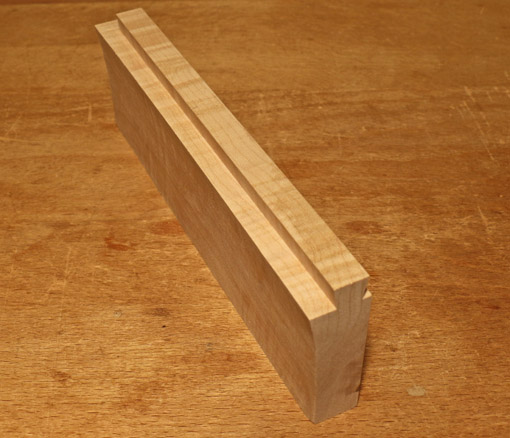

I find this simple bandsaw push stick (above) handy and safe. The key is the hacked-up tip that grips a corner of the work piece. The tip is self-renewing as it gets passed into the moving blade (so my fingers won’t), until the stick gets too short, when it takes only a minute to make a new one.

Now, the irritations:

While A2 steel certainly has merits, it dulls differently than O-1, often with minute chip-outs, even with higher secondary bevel angles. I am also convinced that it must be very difficult to manufacture consistently with regard to carbide grain size, because I have some durable A-2 blades that almost never chip out and some that do so much more often, despite all being from highly regarded makers.

Jorgensen’s otherwise excellent #37 series heavy-duty bar clamps come with soft orange pads that leave oily stains on the wood when tightened hard. (On sanded mahogany in the photo below.) The stains do seem to get obscured by oil or varnish finishes, but are a risk and annoyance better avoided. The manufacturer acknowledged the issue when I contacted them, but I have seen no changes in the product in the more than one year since. I replaced the OEM pads with Bessey pads on the screw end and thin adhesive cork on the fixed end.

This one goes in the DAMHIKT file. I think I’d work outdoors in single digit temperatures rather than do topside routing of MDF in the shop, at least when a router dust collection attachment is impractical. It’s just not healthful.

Another one: Non-tapered sliding dovetails longer than about 3 or 4 inches should be considered a major risk factor for insanity. This was a situation where a tapered sliding DT would not work, but some things are just not meant to be.

It’s all OK though, because making things continues.