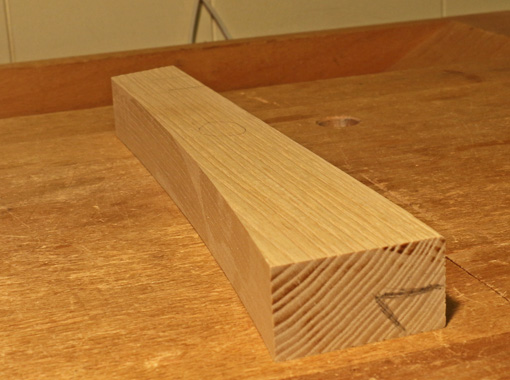

This unpretentious tool, for about six bucks, is surprisingly useful to modify concave curves on fairly narrow work such as table legs. I use it for fast, corrective takedown if my bandsawing has wandered off the layout line, or if I’ve changed my mind about the curve after having sawn it.

Its molded plastic handle and snap-in cutter certainly do not exude cool-tool cachet, but the varying curve of its sole, flatter toward the toe, steeper toward the handle, is quite effective. It cuts on the pull stroke. However, it tends to tear the wood and leave a surface too ripped up for efficiently transitioning to refinement with finer tools.

To remedy this problem, I hone the cutting face with a fine diamond stone. While this sharpens the cutting teeth, it has the more significant effect of limiting their depth of cut. This does make it a somewhat slower tool, but the resulting surface is considerably improved, so the whole process of refining the curve is actually faster.

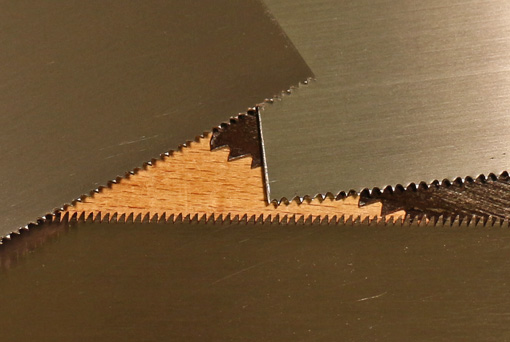

The macro photo below shows the honed teeth, which have been lowered relative to the peaks of the “waves” on the cutting surface. (The cutting edges are facing upward. The honed area is the silvery line visible on each of the two teeth near the center of the photo.) This is similar to the working of an “anti-kickback” router bit, in that it limits the depth of bite of the cutter. If you go too far with the honing, the teeth will have too little bite or won’t work at all, so proceed gradually with the modification and test the tool as you go.

The tooth lines are angled to the length of the tool, pre-skewed, in effect, so I find it works best after this modification by pulling it with little or no additional skew.

A great tool it is not, but it does the job decently well. I wish Stanley (or Microplane) would make a longer version, say four or five inches, retaining the varying-radius curve, with room to place a second hand on the front of the tool. Not currently made, but perhaps a Shinto rasp in such a profile would be useful, or larger rasps in the style of curved ironing rasps, both with a knob at the toe for greater control and power.

Other options for a tool that is curved along its length and flat across its width include: metal and wooden compass planes, Auriou and Liogier curved ironing rasps, shop-made curved sanding blocks, and a new flexible rasp by Liogier that they call “The Bastard,” which I have not tried.

The Stanley Surform Shaver now comes with a bright yellow handle. Nuance that.