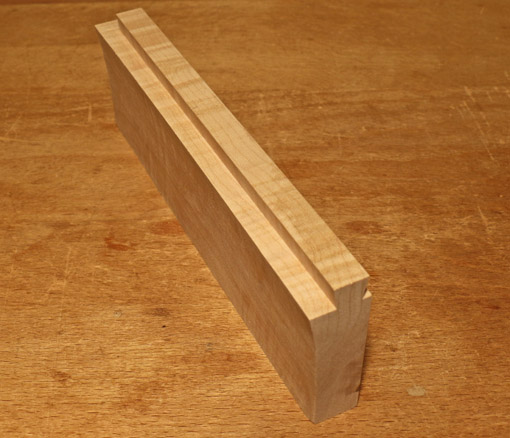

I enjoy incorporating curves in my work and so have explored lots of different tools and methods for shaping, refining, and smoothing them. Years ago I used a new Record #20 compass plane but then got rid of it. The problem, however, was mostly in my approach to the tool. I’ve harbored mixed feelings about the metal compass plane since, but have finally come to peace with the beast since owning this vintage Stanley #20 for the past year.

I’ll get into the function and handling of the tool in the next post, but here I will detail its tuning and modification.

This #20 was manufactured sometime in the years 1933-1941, as best I can tell. It arrived from the seller fundamentally sound – no cracks in the main casting, working sole adjustment, and japanning in excellent shape.

These planes need all the help they can get with chatter dampening so I replaced the thin Stanley blade and chipbreaker with a hefty Hock A2 cryo blade (#BPA175) and chipbreaker (#BK175), 1 3/4″ wide. I prefer the durability of A2 for the way I employ the #20, which I’ll discuss in the next post.

Patrick Leach notes that the #20 (and #113) have unique chipbreakers so I carefully checked the diagram on Ron Hock’s site. The critical parameters are the chipbreaker’s slot-to-edge distance and the length (the short dimension) of the slot. These worked out beautifully. The #20’s advancing fork engaged the chipbreaker slot very well despite the increased thickness of the blade-breaker set. Also, the disc in the lateral adjusting mechanism nicely engaged the blade slot.

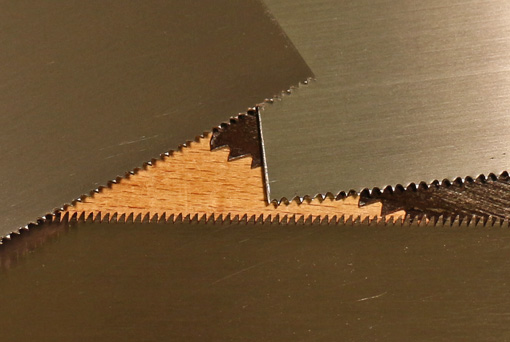

Unfortunately, the thicker blade-breaker set caused severe pleating of shavings, and bad clogging. To remedy this, I disassembled the sole by knocking out the pin at each end of the sole and freeing the dovetailed connection between the sole and the body, then filed the forward side of the mouth to widen it (barely advancing into the row of pins that bind the flexible portion to the dovetail block), and added a slight forward angle to the throat, all to make more room for shavings to escape. It also proved necessary to round over the crisp bevel on the back of the chipbreaker.

This solved the clogging problem very nicely, and the beefy A2 Hock set outperforms the Stanley set! Suprisingly, I have not found the wider mouth to be a problem for planing curves.

The frog needed minor truing. I reattached it as deep as it would go, then, after reassembling the sole, filed the landing below the frog to be mostly level with the frog to increase support for the blade.

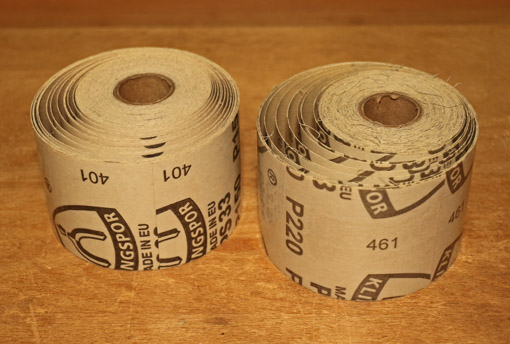

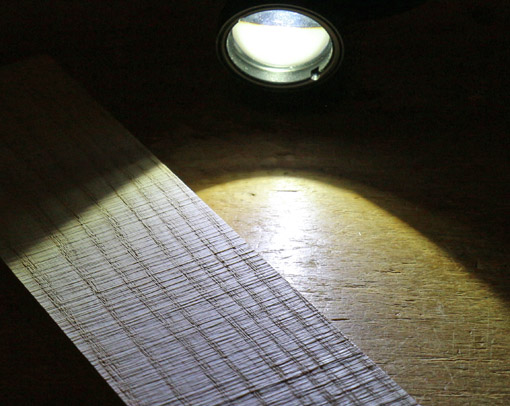

I flattened the sole around the mouth with a diamond stone. There is no point in flattening beyond the vicinity of the mouth in a compass plane with its flexible sole. A general clean and lube, and touch ups with a file here and there, finished the job.

Consistent with the purpose that I assign to this plane, I sharpened the blade with a medium camber and made sure the corners would not catch the work piece.

There are other options in metal compass planes including a Record #20, Stanley #113, other variants of the #113 style, and current versions of the #113 by Kunz and Anant.

The metal compass plane is a bit of an odd animal and one must come to terms with it, as will be discussed in the next post.