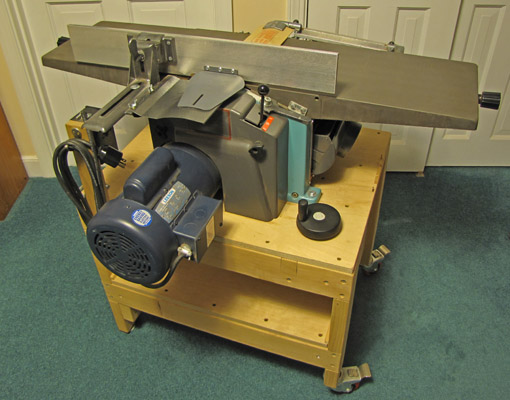

Let’s take a detailed look at the Hammer A3-31.

When considering a new machine or any tool, I first assess the quality of the key parts that cannot be altered by the user but are accessible to direct evaluation. Here’s how the A3-31 stacks up in this regard.

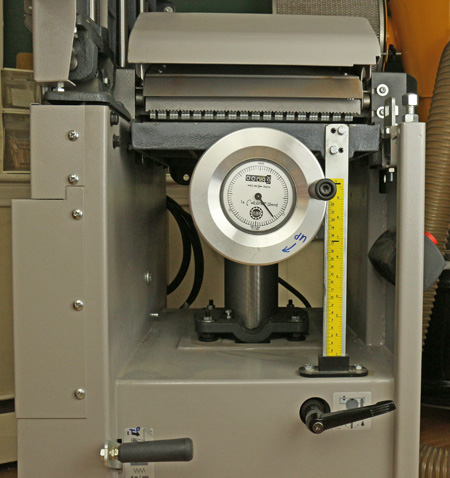

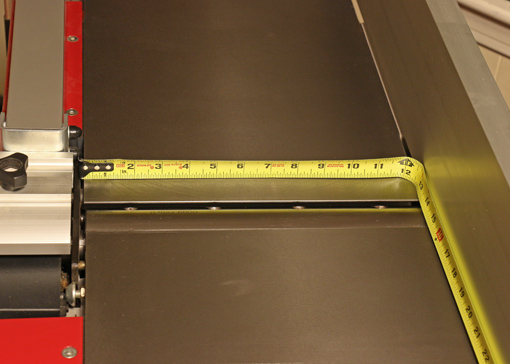

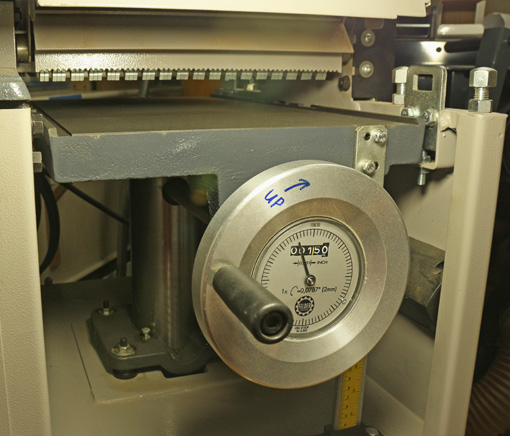

1. Bed flatness is excellent. Against a Starrett straightedge, the jointer infeed table is within .001″ along its length and .002″-.003″ on the diagonals. The outfeed table is just a hair concave along its length, .003″-.004″, and the diagonals are off by only .002″-.005″. The planer table is within .002″ along its length and .003″ on the diagonals.

This all is excellent, well within Hammer’s spec of .006″, and is an important factor in how accurately the machine can be tuned. Furthermore, the beds are heavy and constructed with thick ribbing, as seen above.

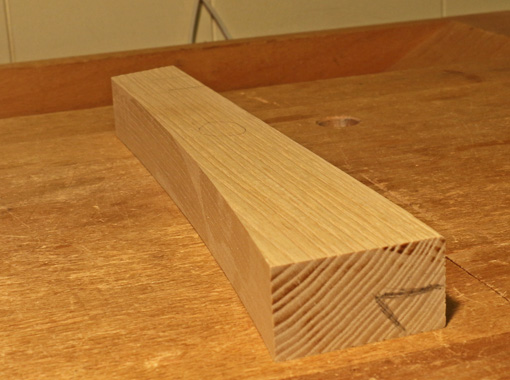

2. The planer feed mechanism does not balk with 12″ wide boards. The steel drive rollers control the board unyieldingly, yet the indentations made by the infeed roller are shallow enough to disappear when the final pass is very light. With good technique, snipe is about as minimal as it gets.

The feed speed is 6.5 meters/minute (21.3 feet/minute), which makes the three-knife cutterhead at 6000RPM produce 70 cuts per inch, typical for jointer-planers in this class. Compared to the DeWalt 735 (with a stock cutterhead) at 96 cpi in “dimensioning” mode and a phenomenal 179 cpi at the slower “finishing” feed speed, the A3-31’s 70 cpi may seem a bit rough but in fact it seems to strike a good balance between producing an excellent surface and working at a good pace.

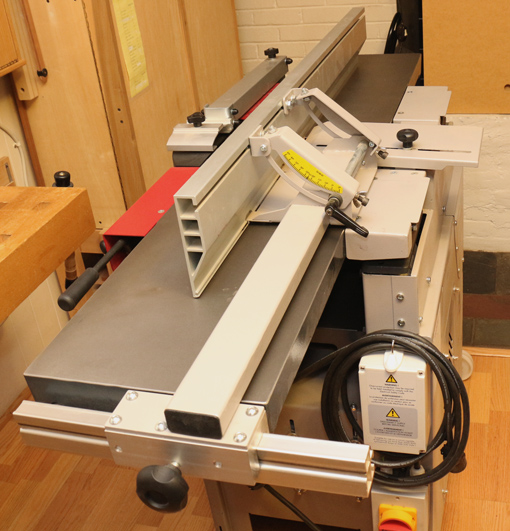

3. I like the Euro-style safety guard better than the spring-loaded “pork chop” style. I always use paddles for face jointing and it is easy to pass the board under the narrow guard, which is height-adjustable using the knob at the far left in the photo below.

For edge jointing the guard can be adjusted laterally to expose the minimum width of cutterhead. It would be better if the guard was hinged so half of it would hang down when it is adjusted very far toward the user side of the machine – but it’s not in that position too often so it hasn’t been a problem. The hinge feature is present on the company’s higher priced models.

4. Dust collection, as I mentioned earlier, is just wonderful, for jointing and planing. This helps a lot in my small shop.

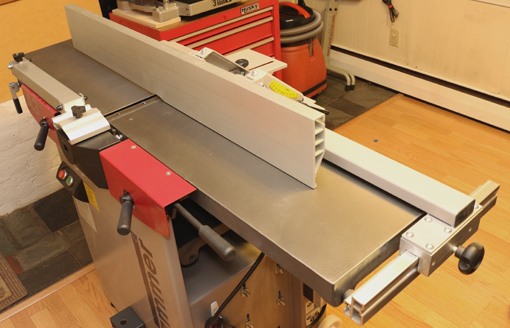

5. The construction of the aluminum fence makes it very stiff. It is flat within .001″ in all directions and I cannot detect any twist. It is adjusted back and forth by using the knob (to the right in the photo below) and sliding the bracket on the extrusion track.

A slight complaint is that the squareness of the fence to the table cannot be made exactly consistent throughout its full adjustment range and most of its length, probably due to minute errors stacking up. However, the discrepancies are quite small, and by finding favorite locations for the fence, I have had no problem getting nice square edges on long boards.

From the back view, you can see that not much sticks out – only the rear cutterblock cover. For most fence positions, the net depth of the unit is about the same with the jointer beds down or raised.

Other key components that I cannot directly assess seem very good based on indirect observations and working with the machine. Machining and part formation looks neat throughout, with no ill-fitting components. The motor has excellent power and does not get overheated. Hand adjusted parts, such as the planer bed adjustment are very smooth, and the machine runs with that nice low hum suggestive of quality.

The same outfit that makes Hammer machines also makes the much more expensive Felder line. A Felder 12″ jointer-planer lists at over $7000 (ouch, my hand just cramped up at the keyboard), which is more than twice the price of the Hammer A3-31. I figure that the expertise and institutional experience applied to the Felder line must bleed over into the Hammer line. I’d bet it’s more than half the machine for half the price.

Next: The final next installment in the series will cover tuning and results.