When making dovetail joints, it is important that the tails, which you’ve cut first (of course, right?), have their sides square to the reference (inside) face of the board.

In practice, depending on the compressibility of the wood species being worked, it may be acceptable or even helpful for the inside width of the tail to be a hair narrower than the outside face. This creates a slight wedge effect that helps ensure tightly meeting surfaces at the outside face of the completed joint.

There should never be the opposite arrangement where the entering width of the tail is wider than the outside face of the tail. That would directly, by the geometry of it, leave gaps on the show face of the joint, making it weaker and less attractive. It would also indirectly create these gaps by corrupting the marking out of the pins from the inside-face edges of the tails.

Thus, as with many aspects of woodworking, this is a one-sided tolerance issue, and we want to avoid compounding small errors.

So, is it really necessary to check the sawn surfaces of the tails before proceeding to mark and saw the pins?

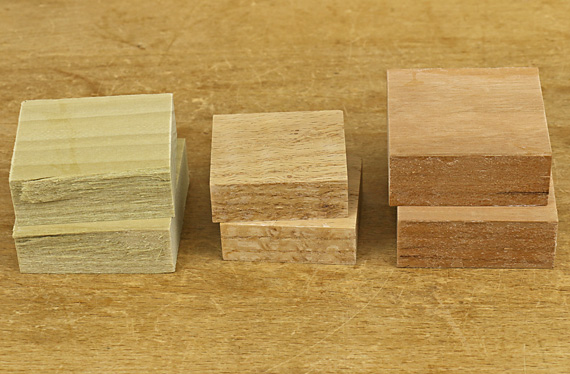

With good sawing skills, frequent repetition, and an easy-going wood, you may need little or no checking. Realistically however, it is not easy to make all the saw cuts right on, and checking takes very little time and effort. And while you or a demonstrator may be heroic in pine, what about oak, shedua, or hard maple? Also, it’s a lot easier to dovetail a 3/8″-thick, 3″-wide drawer side than a 3/4″-thick 12″ carcase side.

I suggest be realistic and reasonably careful in your work without being timid or plodding.

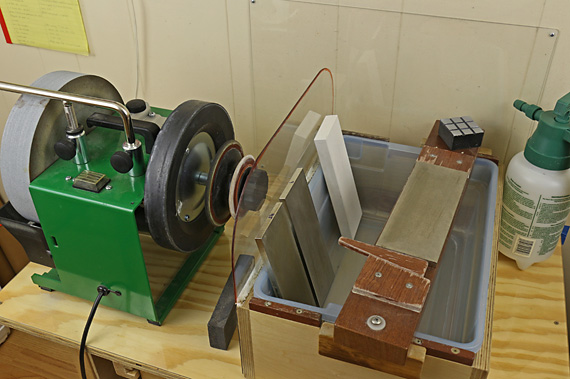

Here is the little square I use to check the sawn sides of the tails as well as the adjustments I make by paring them. I made this tool about 30 years ago.

The beam, made of pre-ban Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra), is about 4 1/4″ long x 3/4″ x 1/2″. The 1/16″-thick brass blade is 11/64″ wide, which can fit between almost any pair of tails that I make. At almost 1 3/4″, it is unnecessarily long – maybe I envisioned sometime making giant dovetails. The square is accurate to less than 0.001″ on both sides, a tolerance not too difficult to achieve in this size tool with patient filing and scraping.

The T shape allows the beam to register on the face of the wood on both sides of the measurement point. This makes it fast and convenient to use. It also averages out any trace of cupping that might have creeped into the board since it was four-squared.

There are two excellent manufactured tools for this task. One is the little (in size but not in price) Starrett 14D square, shown below, which has a blade 5/32″-wide over most of its length that is cut down to a mere 3/32″ wide over the remainder.

A lot less expensive is Sterling Toolworks’ Dovetailing Rule. This blade fits in a 6″ combination square stock (Starrett and others) and has a section just under 3/32″ wide to fit between virtually any pair of tails. Chris Kuehn, founder of Sterling, has produced a practical, commercially available solution.