Maybe. It depends.

The idea is to make the joint “stronger.” But stronger how?

In ballistic and gradual load tests reported in magazines, the M&T joint does not usually fail by the tenon withdrawing, which is mostly what a peg is designed to prevent. Rather, it is the mortise wall or the tenon itself that gives out first. Pegs can and usually are shown to weaken the mortise wall, and probably also the tenon itself. So, pinning does not seem to strengthen the joint against this type of destruction.

A few qualifications are in order. Most tests are done on frame M&Ts. However, in leg-and-apron M&Ts, there is more wood around the mortise and the result may well be that pins are a net benefit in strength.

Also, this discussion refers to glued furniture-sized joints, not timber framing joints. Also, I am not referring to draw boring. In my opinion, this technique has limited use in furniture making unless it is needed to circumvent having to use very long clamps, and even then there are alternatives such as Universal Wedgegrip clamps.

I think that for most furniture, and based on decades of observing my own constructions, the joints will hold up either way. Probably the biggest threat is abruptly shoving or dragging a loaded table across a floor on which the bottom of a leg catches. Also, there is always the risk of abusive handling during house moving. Chairs are a different matter.

But what about slow degradation of the M&T? There, I think a properly placed peg can help keep the tenon shoulder tight against the mortise member as the inherent dimensional conflict may work to create a seasonably variable gap at the shoulder line. Certainly, there are several factors in what happens: the joint dimensions, the flexibility of the glue line, wood species, grain orientation, joint fit, seasonal humidity stress, and more.

And as a practical matter, aesthetic preferences often decide the matter.

Still, I think there is value to pinning the M&T in some cases, particularly when I want to hedge my bets against gaping at the shoulder line. In practice, I have found that it helps. I am more inclined to pin a leg-and-apron M&T than a frame M&T. Maybe luck is a bigger factor than I know.

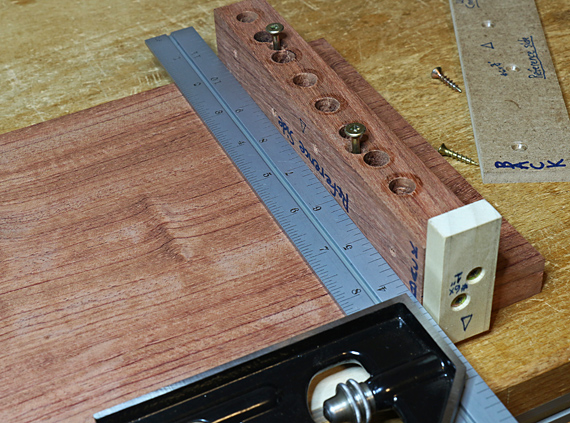

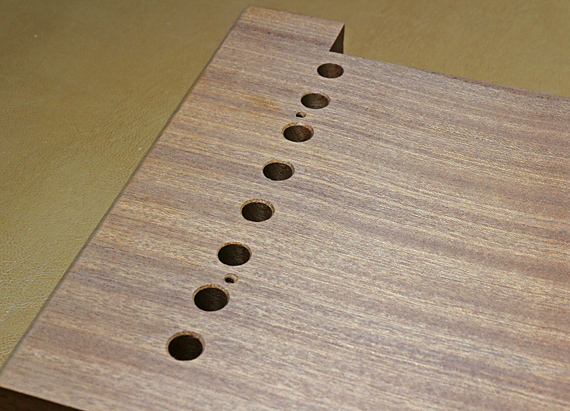

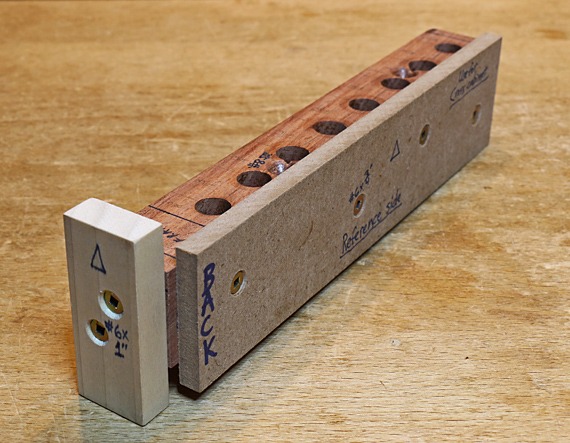

If I am going to pin the joint, I am careful where I place the pin(s). The goal is to have most of the movement of the tenon cheek against the mortise wall occur in the part of the tenon deep to the pin, where it will not create a gap at the shoulder. If the pin is too close to the shoulder, there will not be enough mortise wall for strength. If the pin is too far from the shoulder, that defeats its purpose.