From tabletops to drawer bottoms, edge-to-edge joinery is found throughout furniture making, so it is worthwhile to explore the issues involved in preparing, cutting, and gluing up these joints.

For most of the steps there are a variety of good approaches, particularly based on the size of the joint and the available tools. The outright errors usually come from injudicious wood selection or inattention to the key tolerances in the joint.

As we woodworkers can’t help but notice, edge joints that have opened up can be found everywhere. But why? After all, if the bonded glue line is really as strong as the wood itself, it should not have any more propensity to split than the adjacent wood.

One of the large drawer fronts at the factory-made red oak desk where I am typing has a small edge joint failure. A cross grain conflict with the particleboard sides is stressing the solid wood front but why is the split at the glue line?

Whether due to luck or skill, pieces that I made 25 years ago have fully intact edge joints but, again, why?

So let’s think about this fundamental joint in a short series of posts.

Keep in mind that a little split here and there usually does not affect the function of the piece. My workbench, which I’ve used for more than 30 years, has several splits in its top that don’t bother me one bit. In fact, they seem to function as built-in stress relievers that probably help maintain the remarkably consistent flatness of the top throughout the seasons.

Wood selection

It is surprising how often we see mismatched glueups in otherwise fine work. A door panel with flatsawn cathedral figure running out at a glued edge adjacent to straight rift figure looks like it came from a factory, not the shop of a craftsman. Below is a factory-made door panel that is devoid of human finesse.

It is best to match the figure at adjacent edges and generally avoid edge runout of flatsawn figure. Join rift to rift and quartered to quartered. Cathedral figure boards are best joined where there is rift figure beyond the width of the arches – ideally where the figure lines are nearly straight. Where this is not possible, try to have the figure lines flow into each other across the glue line. In this way, attention is not called to the joint line and the completed panel looks harmonious.

Below, even in this book-matched panel where the halves are necessarily mirror images of each other, the boards blend together and the joint line (indicated by the pencil) is barely detectable.

Joining a quartered-grain edge with a flatsawn-grain edge, for example, not only looks poor but the thickness of each board at the glue line will undergo different seasonal change because of the different orientation of the growth rings. This can produce a tiny but disconcerting step on the surface at the joint line. The joint is stressing itself from this conflicting movement.

In summary, join similar edges to produce visual and structural harmony.

Next: Should you alternate the growth ring orientation of flatsawn boards in a glued up panel? Also, we’ll consider the camber question.

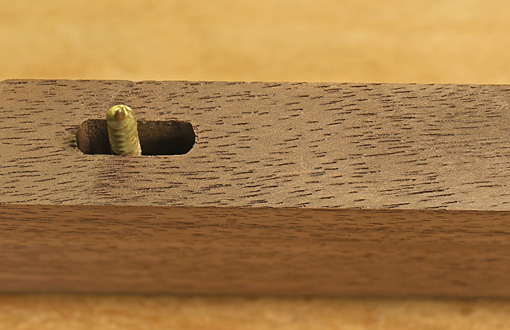

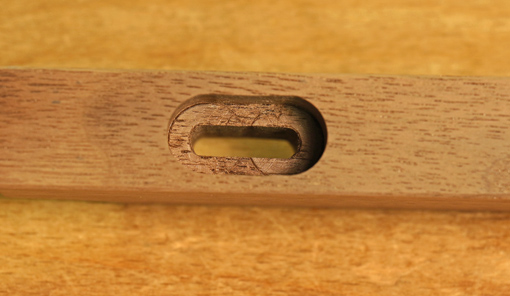

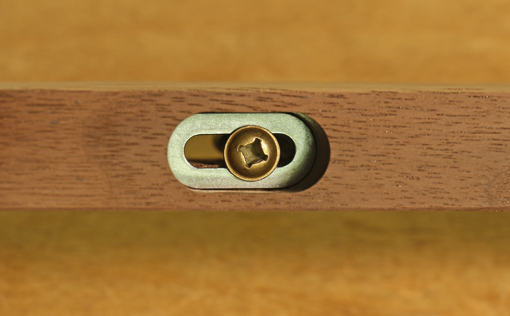

For this type of assembly, I prefer square drive, hardened, deep-thread, washer head screws, #8 in this case, available from McFeely’s. (Technically, this is a combo drive head but who in his right mind, given the choice, would use a Phillips driver instead of a square driver.) Of course, the depth of the large slot must be worked out according to the thickness of the stretcher or runner, the thickness of the piece that the screw will bind to, and the length of the screw. The view from the other side is shown below.

For this type of assembly, I prefer square drive, hardened, deep-thread, washer head screws, #8 in this case, available from McFeely’s. (Technically, this is a combo drive head but who in his right mind, given the choice, would use a Phillips driver instead of a square driver.) Of course, the depth of the large slot must be worked out according to the thickness of the stretcher or runner, the thickness of the piece that the screw will bind to, and the length of the screw. The view from the other side is shown below.