When installing solid brass hardware in fine woodwork, matching solid brass screws are essential to complete the look. However, brass wood screws are weak compared to their steel counterparts and there often is limited depth with which to work, such as in a small box lid.

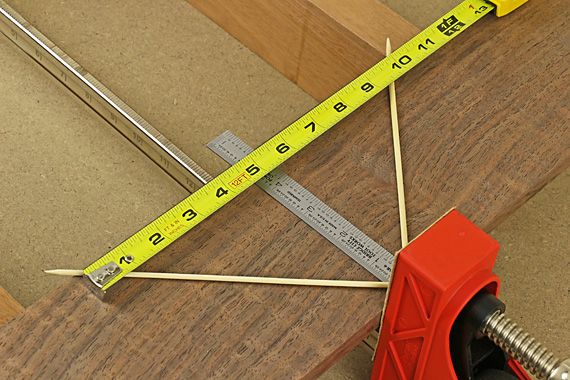

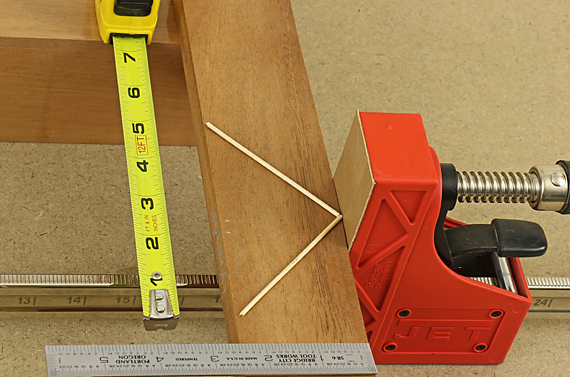

Lee Valley recommends the use of brass machine screws as having much better strength than brass wood screws in short holes. I have tried this with excellent results with 4-40 (above, left) and 6-32 (above, right) flat head brass machine screws. Here are the details.

The why

The machine screw has the advantage of a thicker, non-tapered body that is less likely to break than the wood screw as you torque it down. Furthermore, because the machine screw threads have already been cut by a tap, the screw goes in easily and only tightens as the head meets the countersunk hole in the hardware.

By contrast, a brass wood screw has to cut its own threads and the screw is stressed throughout the range of installation. Yes, you can use a steel screw to pre-cut the threads, but good luck trying to find a steel wood screw with threads that match the pitch of the same nominal size brass wood screw. They usually do not, which means you are simply breaking down some of the inter-thread wood that the brass screw’s holding power depends upon. A recent Brusso hinge set came with such a mismatched steel screw.

Tightening into a properly tapped hole, the brass machine screws feel very solid. I find I can now relax with this method for small hardware installation.

The how

The preparatory hole is drilled at the root or “minor” diameter of the machine screw (the diameter of the screw body without the threads), which yields 100% thread depth when the hole is tapped. Typical work in metal uses 75%, or less, thread depth by using a pilot hole somewhat greater than the root diameter of the screw.

For 4-40 machine screws, the minor diameter is .0813″. This is approximated with these drill bits: 2mm (.0787″), #46 (.0810″), and 5/64″ (.0781″). For 6-32, the minor diameter of .0997″ is approximated with these bits: 2.5mm (.0984″), #39 (.0995″), and maybe 3/32″ (.0938″).

Fortunately, those wonderful folks at Lee Valley sell inexpensive sets of drills in the metric sizes with imperial taps through 1/4-20. In cherry, maple, and shedua (ovangkol), all tight-grained hardwoods, the method worked very well in 4-40 and 6-32. Of course, it pays to experiment beforehand in the specific wood species.

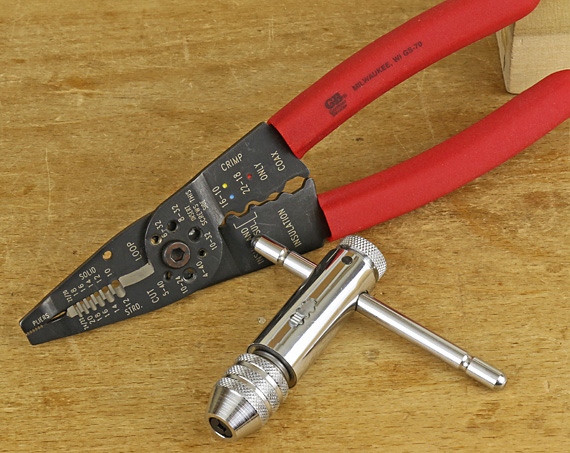

Use a standard-point tap and ratcheting hand tap wrench for most situations, but consider a bottoming tap when you want to eke out every last bit of functional depth. Tap carefully, without wobbling the tool, especially for the smallest sizes whose wood threads are still fairly delicate while in the formation process. Even fine threads in wood are surprisingly sturdy once they are fully filled with the screw, but I like to harden the wood threads with a tiny bit of cyanoacrylate glue. Epoxy is not worth the hassle in my opinion.

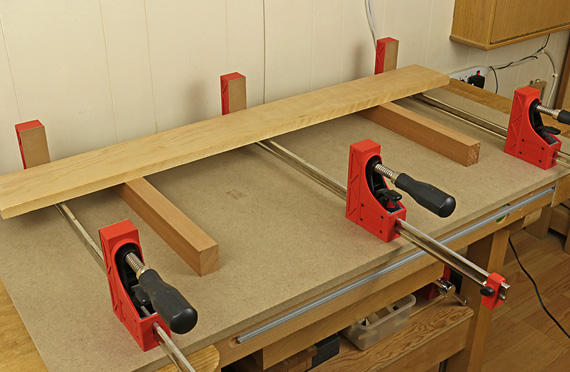

I bought a supply of brass machine screws 4-40and 6-32 in longer lengths than required and easily cut them to length with an electrical multitool (shown), and then filed the cut edge clean.

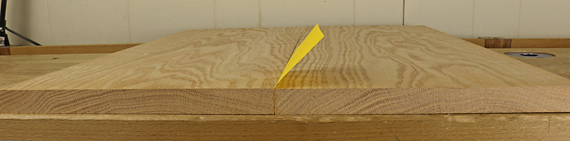

Since we are often dealing with shallow depths and small tolerances, make sure the screw will actually tighten against the countersunk hole in the hardware and not just tighten against the taper left by the tap at the deep end of the hole.

I often prefer to enlarge the countersink and hole in brass hardware if there is room to accommodate the next larger screw size, e.g. 4-40 to 6-32, for more strength.