Before we get to dowel joinery and angled joinery, let’s briefly cover some more options for joining with a pair of mortises and a loose tenon.

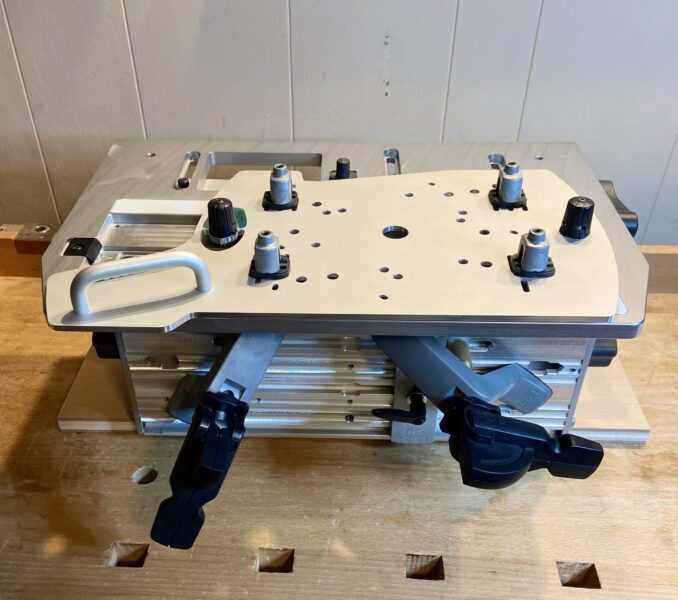

I mentioned the Multi-Router. It has been around for a long time and now done by Woodpecker. Then there is the PantoRouter, designed by a very clever engineer prolifically online. I have not used either of these. Their prices are large but they probably are great.

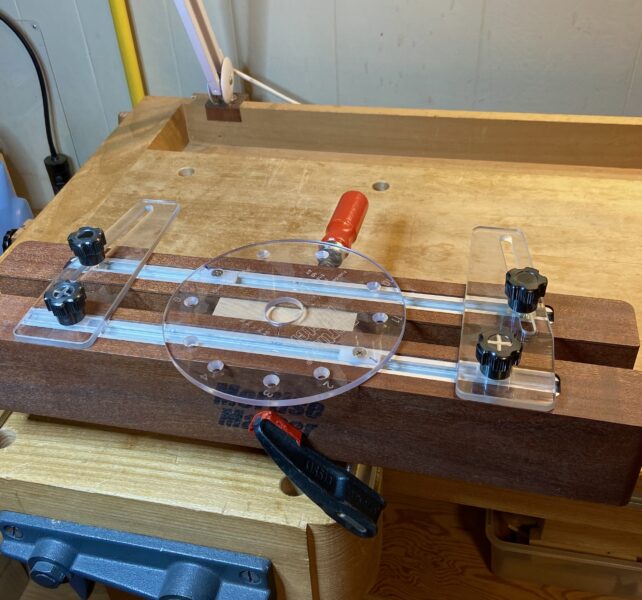

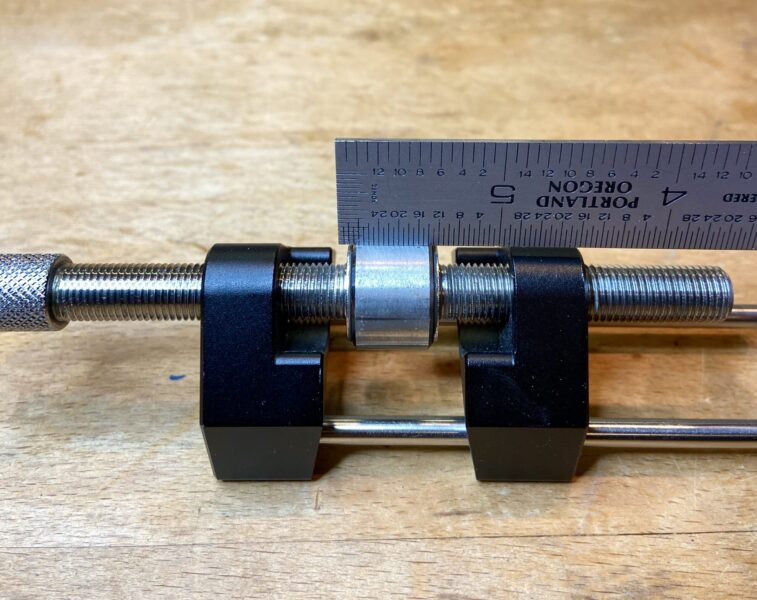

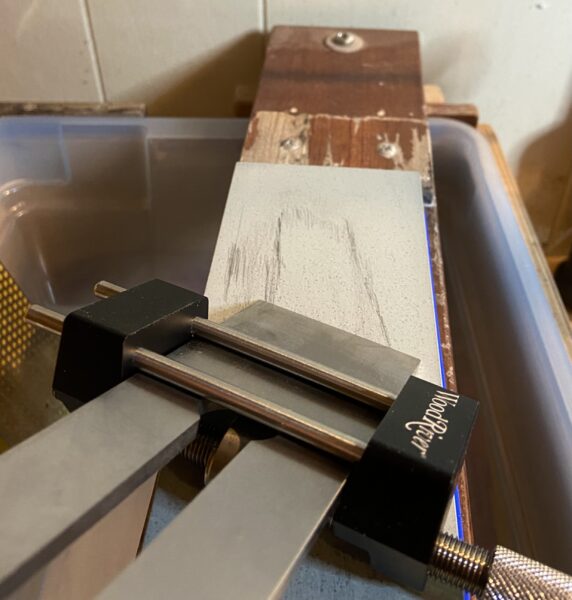

Another remarkable tool is the Leigh FMT. (Photo above.) This makes actual mortise AND tenons. It has precise adjustments for both parts, and a fairly wide range of joint sizes. (Why, I do not know, but I have one, having bought it just days before meeting up with a major brain hemorrhage. See the July 7, 2005 post.)

I see little point in using the tool to make tenons because, as I have said, I see little point in directly making tenons on a half of the joint. (Free tenons are the way to work with rare exceptions.) And because there is some fairly tedious adjustment to make the tenon match the easy-to-make mortise, it will 99% just be a mortise maker for me to use once in a while. It is very good at angled joints, including mortise + mortise with a free tenon.

I have never used a Rockler Bead Lock. It makes a row of linked mortises, into which loose tenons are inserted. From seeing some demos online and trying to understand how it functions, it is not something that will join my shop.

The Kreg Mortise Mate uses a powered drill bit like a router bit. It makes mortises that are similar to Domino but not as good. Apparently, it is related to a JessEs system. Again, though I have not used one, I am not impressed with the performances that I have seen online, nor with the overall logic of the system.

Ok, it is now time to bring in the dowel joint – coming in the next post – and after that, I’ll cover the angled joint. The dowel joint has been fighting for a reputation for many decades. It is often highly underestimated! Even James Krenov was a wide user. Discussion coming up next!