Hell yeah. I just viewed a video (ironically) in which Mark Spagnuolo, the Wood Whisperer, delivers in his usual engaging manner, an excellent perspective on the role of books in learning woodworking. YouTube, he advises, is best used as a supplement to books. Mark is a prolific video producer, so his admonition to continue to use books as the pillar of learning woodworking carries a lot of weight. I agree wholeheartedly.

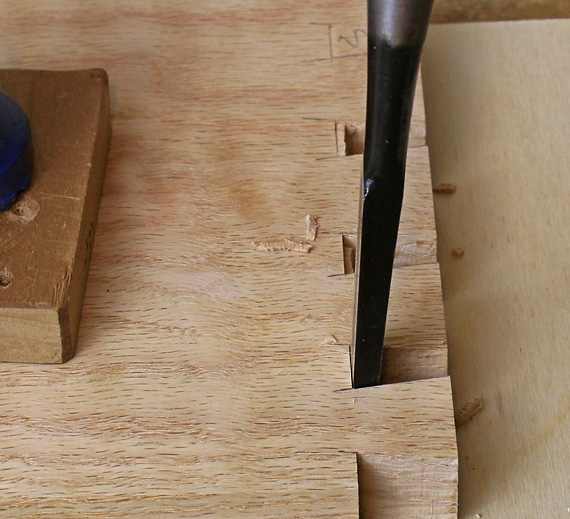

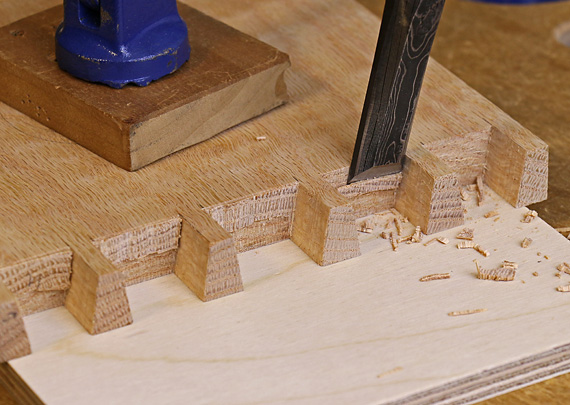

Explaining a woodworking concept by talking it through in a class or video is quite different than explaining it in writing. I may perform a process in the shop, maybe for countless times over many years, and later work through it in my mind to prepare to write about it. Then however, writing about it demands particular precision and clarity, even if accompanied by step photos such as for a magazine article. There is no video to help. The reader benefits from what is hopefully a honed and polished written product.

Similarly, reading and video watching are also different. Of course, video has the obvious advantage of seeing a process happen. Reading, however, gives you a chance to pace your mind, and to make sense of the material and absorb it. In particular, the breadth of a book allows you to see relationships among the material that you are unlikely to realize by only viewing videos.

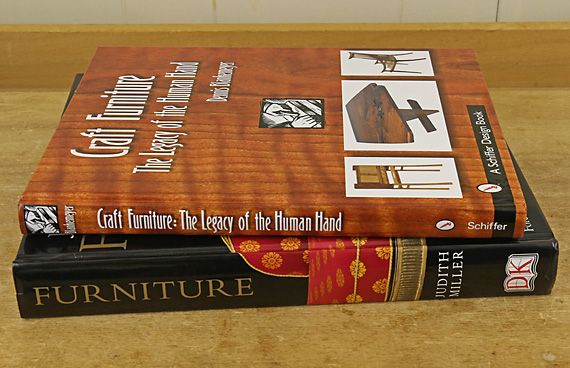

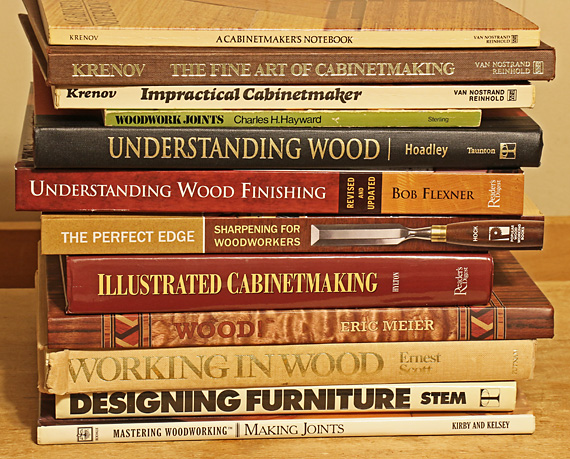

So then, here are my favorite woodworking books. I have mentioned most of these elsewhere in this blog, but I hope this summary is helpful for readers.

1- The Krenov trilogy: A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook, The Fine Art of Cabinetmaking, Impractical Cabinetmaker. JK was a unique inspiring voice for so many woodworkers.

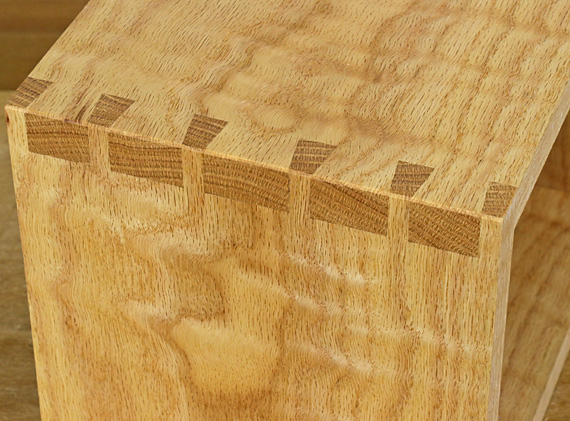

2- Woodwork Joints, Charles Hayward. Ounce for ounce, in paperback, maybe the best woodworking book of all time.

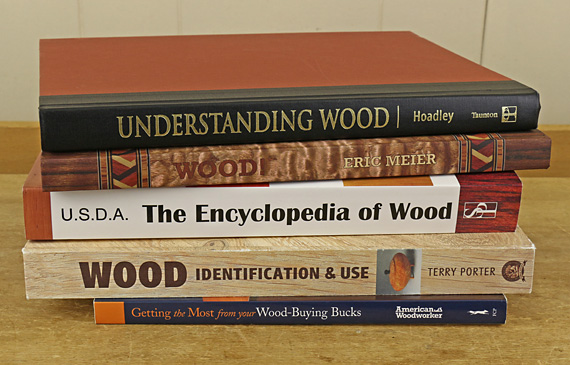

3- Understanding Wood, Bruce Hoadley. How can you even get near a piece of wood without this knowledge?

4- Understanding Wood Finishing, Bob Flexner. I still say that Flexner is the best explainer in all of woodworking.

5- The Perfect Edge, Ron Hock. There is good competition but I think this is the best book on sharpening.

6- Illustrated Cabinetmaking, Bill Hylton. When you have an idea for a project but you’re wondering, “How do I build that?” consult this encyclopedic review of construction options.

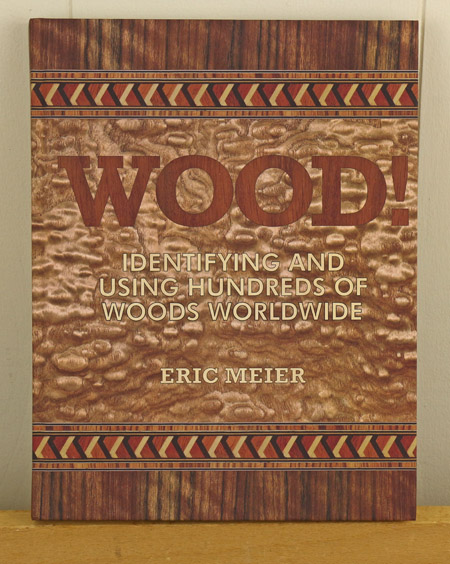

7- Wood, Eric Meier. As good a reason as you’ll find for printed books to continue to exist! Informative and joyful.

The following are out of print, as far as I know, but you can probably find used copies available:

8- Working in Wood, Ernest Scott. It has its imperfections, but this was an enormous help to me more than 35 years ago, along with Hayward’s book. I still find them helpful.

9- Designing Furniture, Seth Stem. Despite using mostly ugly examples, this book teaches design very systematically and well.

10- Making Joints, Ian Kirby. A marvelously clear thinker and explainer. Kirby is an underappreciated author in the woodworking world, in my opinion.

11- In a category of its own, not only because it is available free online, is The US Forest Products Laboratory’s Wood Handbook. Visit the US Forest Products Laboratory site and enter “wood handbook” in the search box.

Also, let’s not forget the magazines. They remain excellent sources of high-quality information.

Oh, and blogs too.