No drop in plate, no router lift, no storage cabinets, no micrometer fence adjuster. So what does this router table have going for it? It’s simple and it works. You cannot buy this one from a catalog. Really, I have nothing against all those gizmos, and maybe they’re right for you, but I don’t think using them will produce better woodwork from my shop.

Overall dimensions are 28″ wide x 20″ deep x 33″ high. The frame is constructed from straight, dry 2x4s joined with half-laps, glue, and 3″ screws. Steel “L” brackets hold the two casters just a bit above the floor when table is planted, so the wheels can engage when the table is slightly lifted from the opposite side to move it about. One leg has a leveler. An electrical switch is located at the upper left of the frame. Most of my bits are stored in the box which I slide out of its cradle before using the router table.

Looking from underneath, you can see two cross supports half-lapped in place to form additional support for the top. After constructing the frame, I used a hand plane, straightedge, winding sticks, and a fair dose of patience to ensure the top edges of the frame composed an accurately flat plane upon which to attach the top.

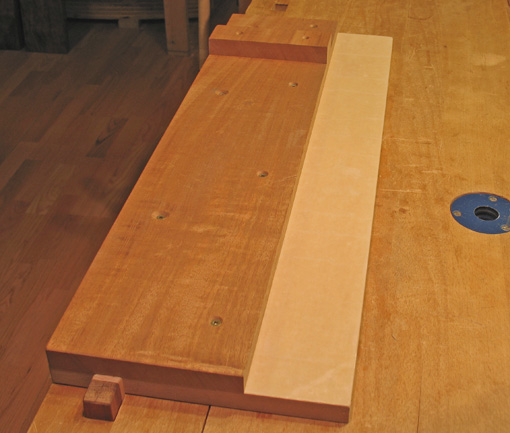

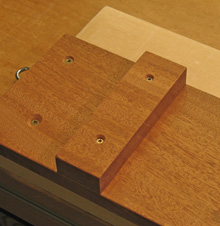

The top is 3/4″ MDF, toughened with a few coats of oil-varnish mix, screwed to the base. An extra Bosch 1617EVS base always stays screwed underneath. In this decade I haven’t found use for a bit too big for the 1 5/8″ hole which is centered in the top. (Maybe I’m just boring.) The top is ridiculously flat and never sags. (Which keeps me happy.) There is a small hole near the bit opening for a rarely used starter pin.

Yes, I must squat to put the router motor in the base – it’s ok. While down there, it is easy get a good angle of view to set the bit height with a rule, a reference block, or most likely, a previously made part of a project. The Bosch base has a simple micro-adjuster with 1/256″ (about .004″) gradations allowing precise readjustments after running/measuring a test piece. The same Bosch motor is used in a second base for hand held work.

So far we’ve got an inexpensive, extremely stable, accurate table. I credit router expert Pat Warner for this general philosophy of the router table, with modifications. My fence, however, is much simpler than his and will be discussed in an upcoming post.