We want to build. We want to work at a pace and get things done.

The key to working at a craft the way we should work – where the job is done well and we are well – is to coordinate the pace of four factors. Let’s consider what’s really going on when we work.

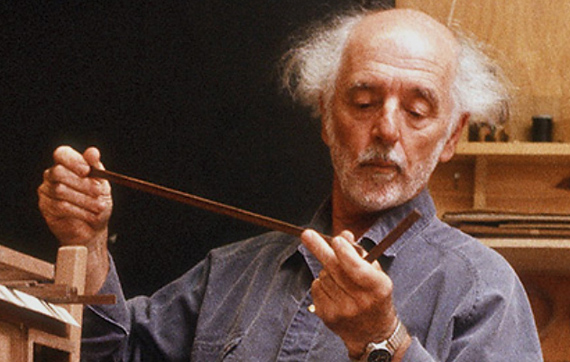

The hands must work with clear intent, guided by skill embedded into muscle memory. For most good craftspeople, this is usually not a limiting factor. Rather, the hands that can easily run ahead of the other factors, which leads to awkwardness and fumbling. We all know what happens when the hands rush ahead of the brain. You neatly saw on the wrong side of the line or cut yourself with a chisel that you’ve picked up a thousand times.

The mind must focus unwaveringly on the specific task at hand, yet maintain cognizance of its place in the overall mission. The mind, of course, governs all and so is the master pace setter. Try to outrun it, and trouble comes: “How did that happen?” – a surprise mistake that really isn’t surprising. Skill of mind is the greatest skill.

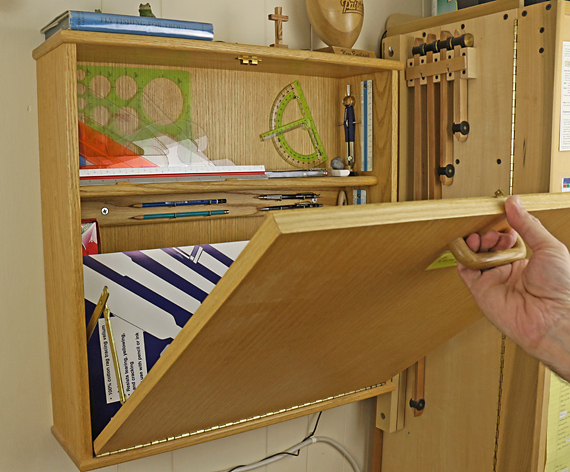

Each of our tools must be put to work within the range of its intended purpose, not forced beyond it. So, maybe you should chop that waste in two passes, not one. And the tablesaw has only so much horsepower. Push a tool beyond its limits and you’ll both pay the price. For a craftsperson, knowing your tools is almost like knowing yourself.

The body must be respected with regard to energy limitations and fatigue. It is not a machine. Usually, posture is the first thing to break down. When core stability breaks down, the fine motor tasks performed by the hands will suffer. If your work is becoming less accurate as a session in the shop proceeds, consider that core/posture fatigue may be the cause.

When these four factors are exerting synchronously, you are happily at ease and do good work. This is peaceful productivity and efficiency – the way we should work, and the way things best get done.

Sadly, many, maybe most of us, are pushed in our pay-the-bills jobs with little regard for the truths of human work, driven by the fantasies of those who do not actually do the work but instead tell others how to work. (Anyone remember Lucy in the chocolate candy factory?) Appreciation of the work dissipates. We become detached from it, and from ourselves.

Happily being human almost always includes integrating our various faculties, being cautious not to neglect parts of our true nature. Hopefully, we can work well in the woodshop as we produce, and do so with joy. Work is best when we pace it this way. And it is the way we live best.