The DeWalt DCW210 is a cordless 5″ random orbit sander that is powered by the company’s 20-volt lithium-ion battery system.

Smitten with DeWalt’s 20V Max series of tools, it is a bit like dealing with Apple stuff. I know I’m being played but the products are just darned good.

Handling is excellent. Weight, vibration level, and control are comfortable. With a top grip, the only option, the sander tends to meet the work squarely with no tendency to tip or gouge. At least with a smallish 2.0 amp-hour battery, balance is excellent. The rubberized area enhances the feel, and the on-off switch is easily accessible from the grip position.

This is a finishing sander, not a stock removal hog. In that context, it has plenty of power. It is similar to my Bosch ROS20VS, if not more aggressive. The DCW210 has a standard 8-hole base with hook-and-loop disc attachment, and runs with a 3/32″ diameter orbit. The brushless motor is very efficient, so I read. It has a variable speed dial, also accessible from the grip position, but I rarely use that option on a sander.

You’re going to love this as I do: the motor brake stops the motion immediately when you hit the power switch. Hallelujah!

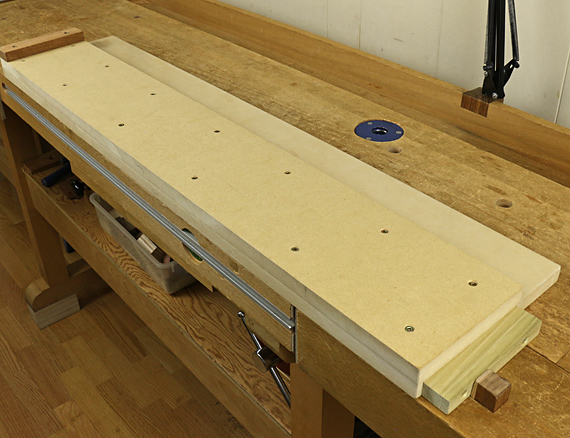

Dust collection with the onboard bag is surprisingly good but of course, no match for sanding with a vacuum hose. (I vacuumed up the tool nice for the photo.) The bag’s good-sized plastic collar and locking system makes it easy to use one hand to detach and attach with a nice positive click. A spring that lines the bag can be compressed and popped to “shake out” stubborn dust. I find it is more useful for allowing a vacuum hose to thoroughly clean out the bag without it being sucked into the hose.

The outlet diameter will not fit standard shop vac hoses but this does not matter to me because using a cordless sander with a hose would pretty much negate the advantages of having no power cord. So I will use this sander without tails of any sort.

I cannot offer data on how long the battery charge will last. After a while of sanding, I check the charge-level indicator on the battery and replace it if it is low. With just two extra lightweight 2.0 Ah batteries on hand and using the DCB113 charger, I could keep working indefinitely. You can also buy higher capacity batteries but I guess at some point the weight would get uncomfortable. Anyway, this is a finish sander suited for relatively light work. Note that DeWalt charger models vary considerably in their charge time.

I will still use my bigger Bosch 3725DVS (3/16″ diameter orbit) with its cord and a vac hose for heavier work but the DeWalt DCW210 is now my go-to tool for finish sanding.

This review is unsolicited and uncompensated. I just want to help you choose good tools.