Wood has figure that was created from life, which, in turn, helps bring life to a creation in wood. Throughout designing a piece, choosing wood, and building, I want to make the most of what the wood has to offer so a synergy develops between the design and the wood. This is not aluminum, Corian, or clay upon which a design is imposed; this is wood!

When cutting curves in wood, it is helpful to predict how the figure will change. The figure should work with, not fight, the contours of the piece. The interpretation of that task is subjective but it pays to be aware of and work skillfully with the figure. (Bent lamination, by the way, is a different matter.)

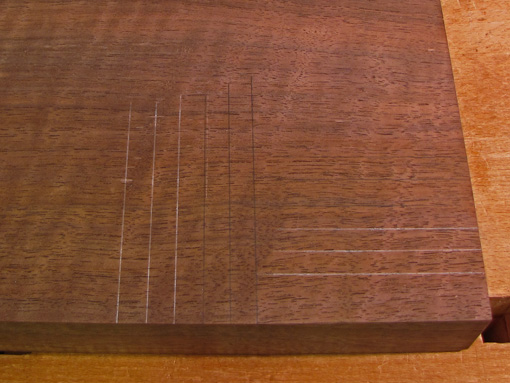

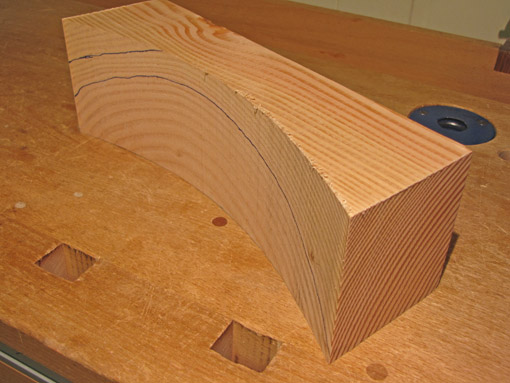

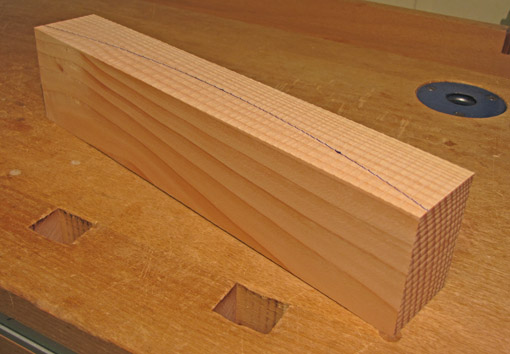

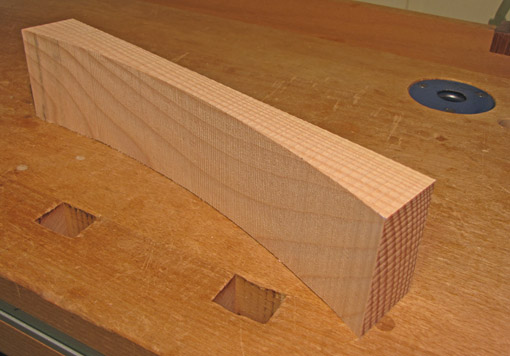

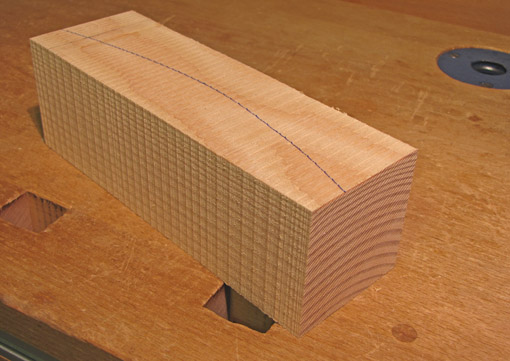

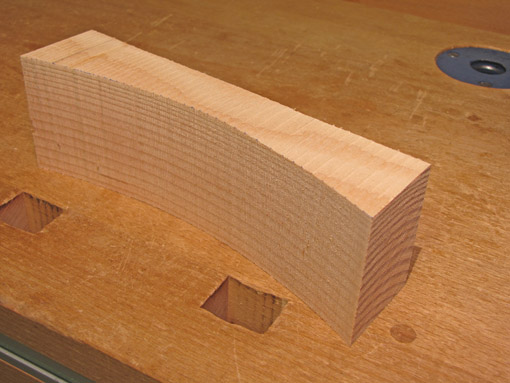

Here is a visual guide to some of the issues that arise in curved work. I used home center Douglas fir which has obvious figure lines created by the large difference between the earlywood and latewood. This is for purpose of illustration, it is not meant to be pretty.

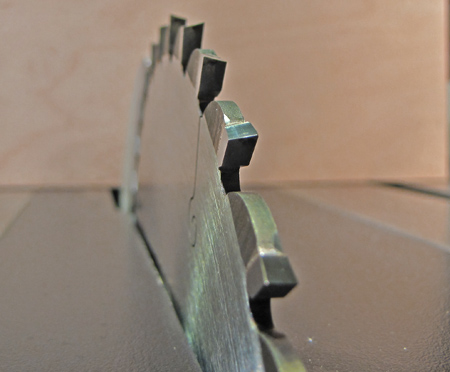

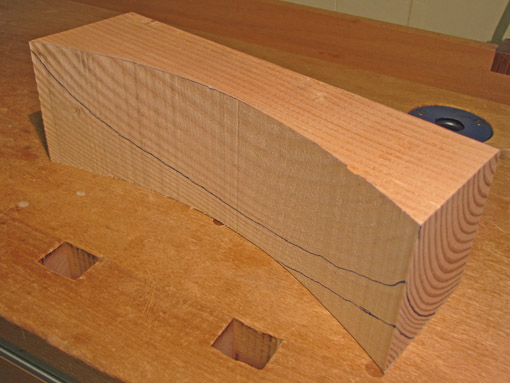

In the photo above and the next two below, a concave curve (marked on the top surface) cut into the rift face causes the figure to bend. The end grain is emphasized with pen lines to show that the annual ring lines go downward as you go deeper into the wood. Thus, the concave curve creates a smiley bend from the straight face. A convex curve would do the opposite.

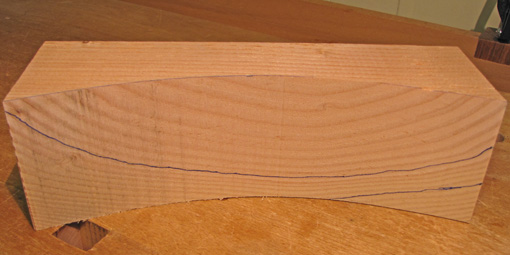

Below is the result if we started with the block with the opposite face on top. (I just turned the same block upside down.)

Now let’s cut a similar curve into a nearly-flat-sawn face. The end grain lines meet the face at an extreme angle and so the figure changes rapidly as we cut the depth of the curve. The result is, to my eye, unattractive. Some of the figure lines run off the resultant face at the bottom and jump on at the top.

Now let’s cut the curve into the quartered face. Since the annual ring lines meet the face at about 90̊, there is almost no shift in the direction of the figure after the curve is cut.

Of course, many other variables come into play, including the depth and consistency of the curves, and their placement in the piece. None of this would matter much in basswood which is nearly absent in figure.

The main ideas:

- appreciate that the figure changes as curves are cut into wood

- it is helpful to be able to generally predict how the figure will change

- use this to the best advantage of the wood and the piece you are making.

Next, we’ll look at how this applies to curved legs. The appreciation of figure and legs, now there’s a worthwhile topic.