Here are the other rasps that have been useful in my work. There are, of course, many more specialty rasps available than discussed here. Hopefully, you will have the opportunity to use high quality rasps that are suited for your work.

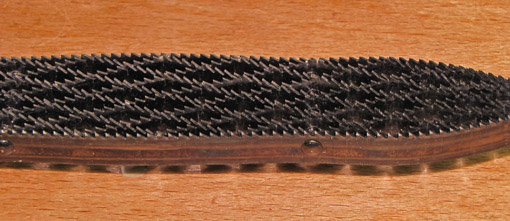

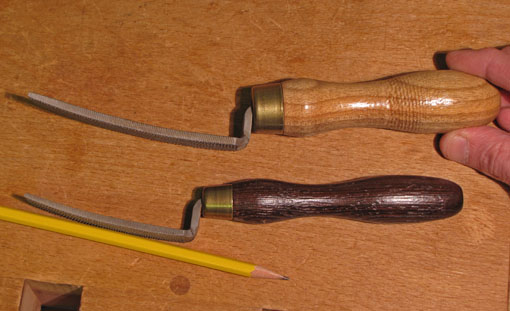

For the enjoyable work of shaping table legs, the Auriou curved “ironing” rasps have been very helpful. Pictured are the larger #8 grain, 1-1/8″ wide, and the #10 grain, 3/4″ wide. (I do not see the #8 grain available now, but there is a #9.) This type of rasp has a shallow curve along its length, useful for the gradual concave curves found in legs and other work. These smooth-cutting tools give excellent feedback to the hand when fairing curves.

Half-round rasps can be used to fair these curves but there are some disadvantages. As the convex face of the rasp is angled to the length of the leg, the contact profile is asymmetrical and often becomes confusing to feel. Also, there is less contact length, somewhat like a short-soled plane, and this makes it harder to feel the lumps and bumps that must be removed to fair the curve. There is also more tendency to tear the wood fibers. Do not be tempted to hold the rasp almost parallel perpendicular to the length of the leg because the teeth will slice the wood like tiny knives, you will not be able to control the rasp well, and deep scratches will be created; not how a rasp should cut.

Now, let’s say you’re at the bandsaw and both your mind and the cut wander, hopefully on the safe side of the line, and you end up with a lump on your otherwise nice leg. Hack it down with this beast, the Surform shaver. Don’t expect a lot of control or a uniform surface, but it is cheap and works quickly.

Click the thumbnail below to enlarge.

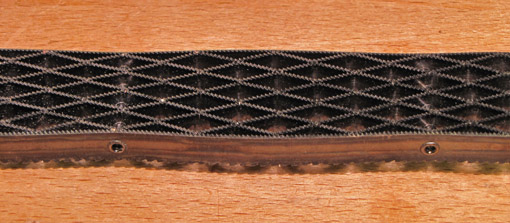

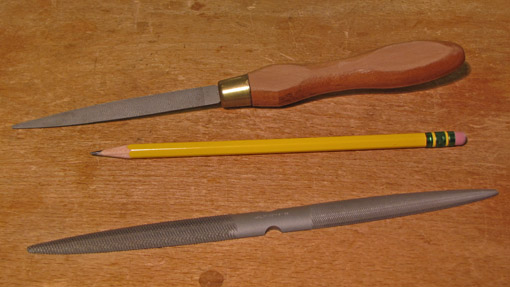

Returning to refined tools, for detail work, the Auriou #14 grain modeler’s rasp can be a lifesaver. It is thin and can be exquisitely controlled. It leaves only a very shallow scratch pattern, but can be made to remove wood remarkably fast for its size and grain.

Similarly useful, though a bit less smooth-working, is the Grobet detail file. While not a true rasp, its double-cut file pattern makes it function similar to a rasp. It is also versatile – four faces, flat and convex, each in coarse and fine.

Click the thumbnail below to enlarge.

The larger round rasp is an inexpensive model from Lee Valley. The round needle rasp, made by Corradi, is helpful for various detail work such as enlarging holes. The handle, also from Corradi, has a chuck which allows the rasp to be removed.

Click the thumbnail below to enlarge.

This wraps up the rasp series. I hope it has been helpful. A final thought: it is easy to underestimate the value of a quality rasp. They are not pretty tools, but they can make a big difference in your work.