A key question for any woodworker acquiring a basic set of tools is which handplane to buy first. As with all tool questions, the answer depends on the type of work you will do and your available money. Furthermore, these issues always involve a large dose of opinion because there are multiple ways to get jobs done in woodworking.

For general furniture making, I suggest first get a jack plane. If you have a lot of money and can make a strong commitment to woodworking, go ahead and get a top quality set of these six planes: smoothing, jack, jointer, block, shoulder, and miter. For such a set of Lie-Nielsens, the cost would approach $2000 and, though surely worth it for an avid woodworker, is hardly a likely leap for a novice. Yet, you must start somewhere, and an incremental acquisition of tools, with adjustments based on the work you decide to do, is a reasonable path.

A jack plane is an excellent tool for stock preparation and can perform well, though admittedly not ideal, for smoothing, jointing, and shooting. As an only plane, a smoother would be deficient in truing work, and it would be very awkward to use a jointer for finish smoothing. Later, when you get the full set of planes, the jack will still be very useful. I originally used my Record jack for all those tasks and gradually got more planes. With a full complement of planes, I still use it more than any of the others and I also have a bevel-up jack.

The options are: buy a new Lie-Nielsen or other high quality plane, fix up a high quality vintage plane, fix up a mediocre new or old plane, or make your own wooden plane. With the exception of the first option or two, it is best to get a good aftermarket blade such as a Hock. The edge durability of A2 steel makes it a good choice for a jack. Keep in mind that the potential of a fixer upper will be limited by its inherent qualities such as the frog design, weight of the casting, and the adjustment mechanisms.

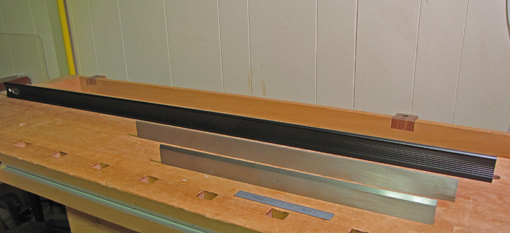

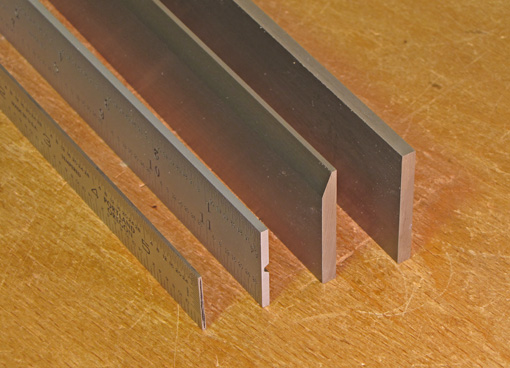

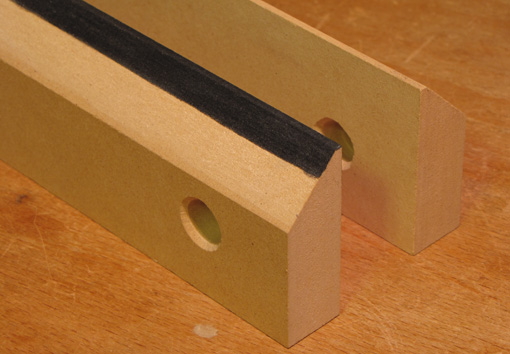

Bevel-down and bevel-up both work. For either, it is helpful to have one or two extra blades sharpened to different angles and cambers to accommodate different work. You can shoot with a BD plane (I did for years) though for this a BU design has the advantage of a heavy blade that is supported very close to its cutting edge. A BU plane makes it easy to change to a blade sharpened to a higher angle for figured woods, but a back bevel can similarly be used on a spare blade for a BD plane. I find BU blades harder to sharpen, primarily because of the wear created in use on the flat side of the blade. To choose for an only plane, I’d go with the BD, but this is my bias. The bigger issues are quality, tool preparation, and skill.

Please don’t buy a block plane as your first plane, as is often recommended! While useful, it is far more limited than the jack. It is a one-handed tool used mostly for chamfering and small trimming work that can often be done with a sanding block. You cannot prepare stock with it, true surfaces and edges, or use it as a smoother. Step up to the big leagues right from the start and get the jack.

Even woodworkers who do almost all machine work will benefit from a jack plane. For most hand-machine blended woodworking, you could do quite well with a jack plane to joint the faces and edges of boards and a portable thickness planer to get the brute work done. Add saws, chisels, marking tools, clamps, sharpening equipment, and, of course, a workbench and you’re in business. Get a bandsaw soon.

Go make something – anything – and enjoy it!