Now let’s turn our attention to the face grain side of the joint where the grain of the dowels is perpendicular to that of the board. This is similar to a multiple mortise and tenon joint but among the important differences is that, because the dowel is round, there is limited side-grain-to-side-grain glue surface. So, it is reasonable to question the glue adherence of the dowel in its hole.

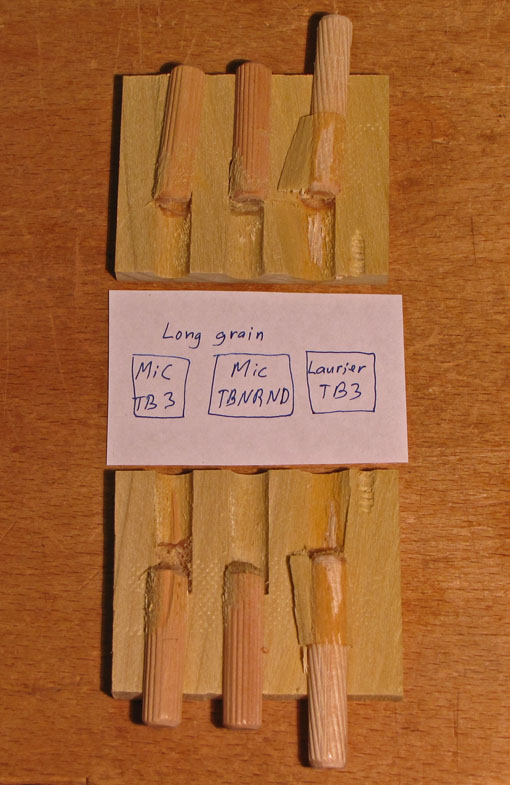

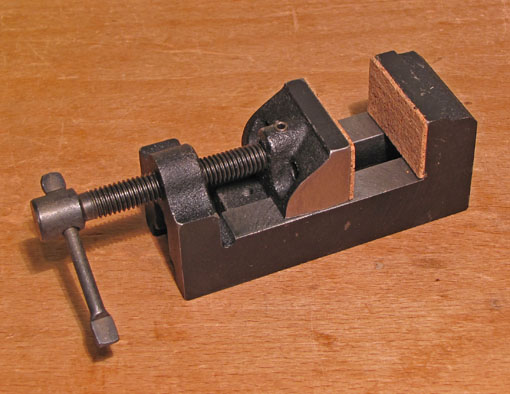

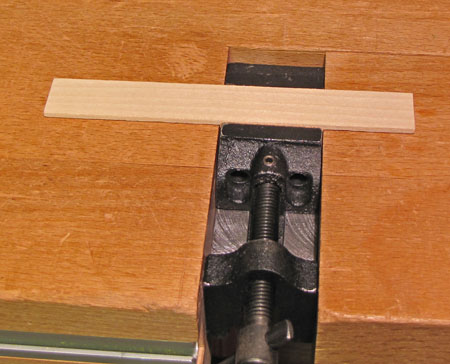

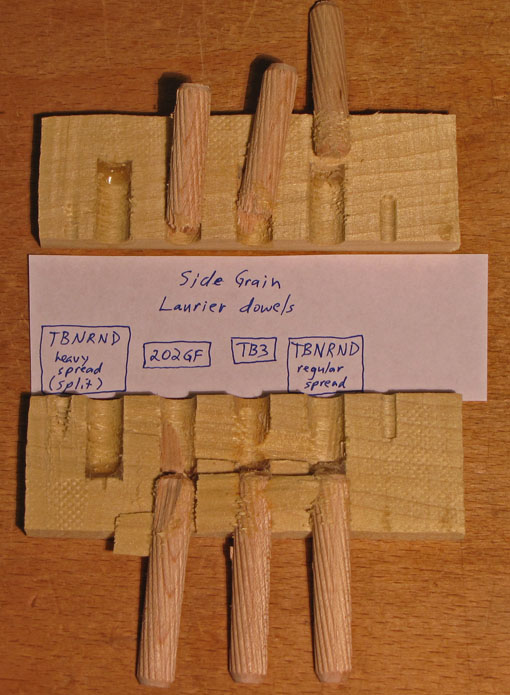

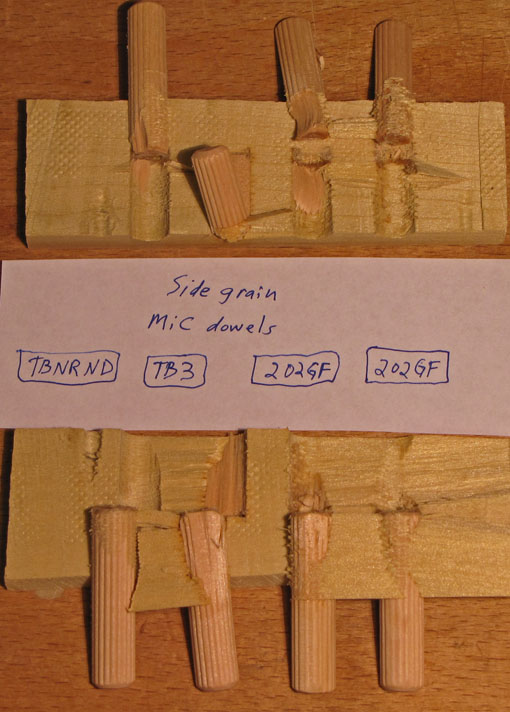

To mimic and investigate this part of the joint, 3/8″ diameter Laurier and Made-in-China dowels were glued 3/4″ deep into holes drilled with a brad point bit. The next day, the wood was resawn through the middle of the dowels. The dowels were then smacked to failure as described in the previous post. The orientation of this procedure primarily examines the adhesion of the dowel to the side grain portion of the hole.

As seen in the photos above, both the Laurier and the made-in-China (MiC) dowels performed well with both Titebond III and 202GF glues. The Laurier dowels were preferable in the long grain side of the joint, so they are my choice for dowel joinery, along with TB3 or 202GF glue.

Titebond No Run No Drip (TBNRND) glue did not create good adherence, and a heavy spread of it in one of the holes caused enough resistance to inserting the dowel that the wood split. It is an excellent glue for some jobs but I don’t think the best choice for this one.

Dowel joints have the same sort of cross grain dimensional change conflict as, for example, a multiple mortise and tenon. Nonetheless, I find these tests reassuring regarding the quality of the glue line in dowel joints.

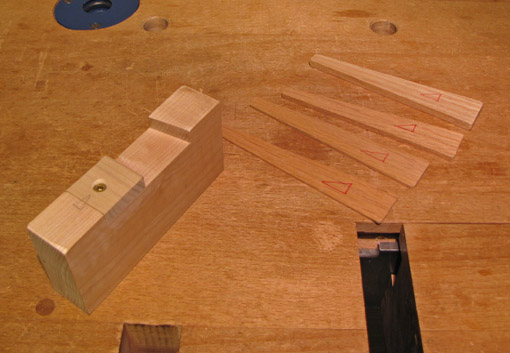

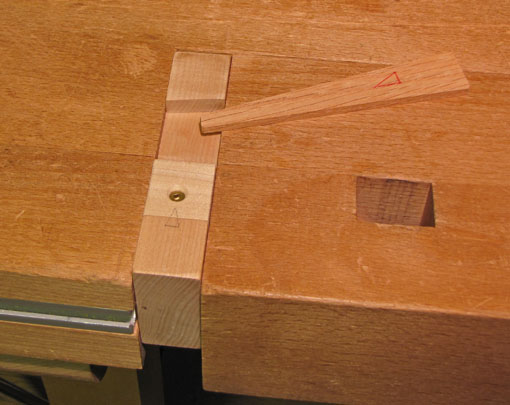

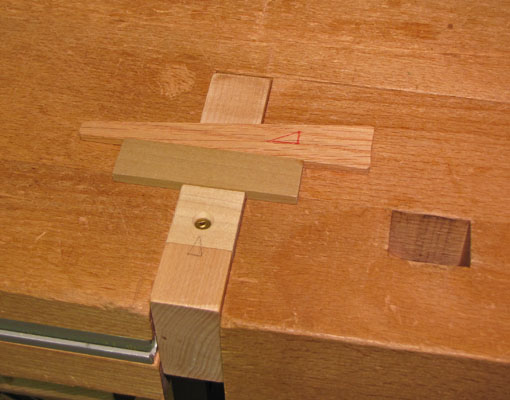

Here is another reason I prefer Laurier dowels. Their spiral grooves are shallower than the straight grooves of the made-in-China (and similar) dowels, as seen in the photo below. After a 15 minute soak in water (the second photo below), which mimics the response to water based glues, the Laurier grooves expand more to take up the space in the joint. The Laurier grooves are formed by compression, and therefore will retain their expanded profile.

But wait, there’s more! The most suspect issue with a dowel is how it adheres to the end grain glue surface in its hole. That will be addressed in the next post.