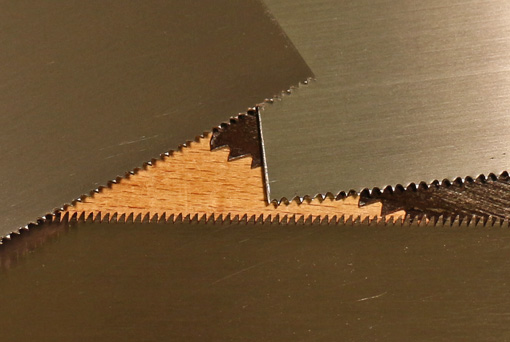

A nice byproduct of messing around with photography using a fancier camera has been that I think I’m also improving my seeing skills for woodworking. By this I mean learning to better observe and process visual elements of composition and design.

The simple key is that this takes effort – it’s not automatic – and it takes practice. Sure, it’s easy to have an immediate reaction when confronted with a creative work. “Wow, beautiful,” or “Please, you’ve got to be kidding.” This sort of intuitive response does have its place and value, and, at the other extreme, over analysis is probably capable of dissolving any creative work into boredom.

Between the extremes there is a very valuable habit of pausing, observing, absorbing, and seeing what the maker has in mind, including if the maker is you.

It is similar to the difference between quick snapshots versus truly observing and appreciating the light and visual elements before you, then using your technical skills to compose a satisfying photograph.

Among many woodworkers, including me, there is a tendency to too soon get absorbed in the intricacies of construction and joinery. Pause and see first, I tell myself, and in this, photography is good training. Photography is humbling because so often the photograph shows you that what you thought you saw when you took the shot is not quite so.

It is amazing what the trained brain can see. During a guided walk in the woods with an expert naturalist, I marveled at his ability to spot interesting things that I walked right past. Yet, in the more subjective landscape of designing and making good work in wood, I think one must be similarly astute.

The main thing is that, just like cutting joinery, it takes effort and practice.