The review of router tables and lifts in the Fine Woodworking Tools and Shops issue (#237, Winter 2014) prompted me to again think about the subject. I have to admit, after reading about all the nifty gadgets, I was tempted to complicate matters and foul up my happily working simple system, which is described here, here, and here.

Naaah.

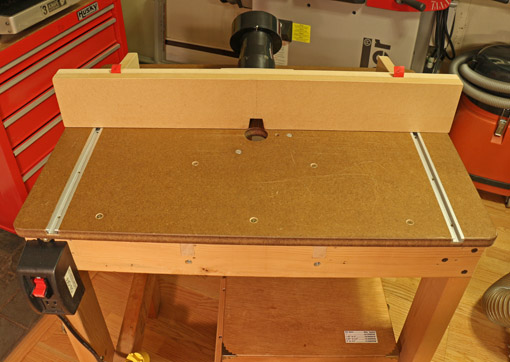

I recently added a T-track system instead of F-clamps to lock the fence in place, and a while ago upgraded to heavy-duty locking casters, but otherwise the setup is the same. There is no removable plate, no router lift, no above-table height adjuster, no fence microadjuster, no miter gauge track, no above-table bit removal, and no insert rings. No shoes, no shirt, no problems.

So, how does this home grown model “Easy 2” stack up against the models reviewed in FW? Let’s look:

Price: At a total cost of about $180, which includes the extra Bosch base, the Easy 2 is $470 less than the “Best Value” and $920 less than the “Best Overall” system in the review.

Flatness: The E2 has an intended crown of .003″ over the full length of the table, and, owing to the lack of an insert ring, a deviation of less than .001″ in the critical area around the bit opening. This beats all the models tested with the possible exception of the Festool, which has a .002″ dip. I agree with the author that a slight crown is preferable to a dip. I disagree, however, that a dip as high as .030″ is acceptable for quality work.

The Big Easy achieves this fine accuracy by employing the wonderful flatness tolerance of stock MDF plus shims. Here is the undercarriage of the table with supports across the width of the table near the router base, along with blue tape shims, aka “microadjustments.”

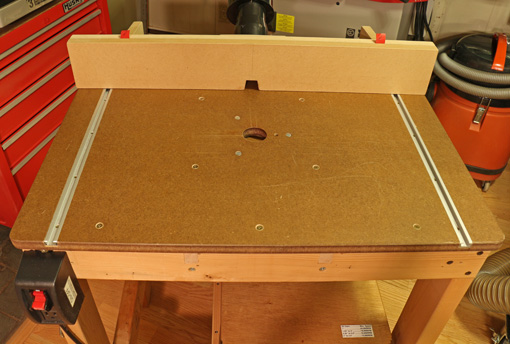

Fence: The E2’s continuous fence is flat and square within .001″. A split-fence attachment is easily installed and removed with finger knobs.

Here is a rear view of the fence locking system:

Dust collection: With simple fittings available from Rockler, the E2 is probably as efficient as all of the tested models except the two with enclosures.

Bit height adjustment: The Bosch microadjustment dial easily allows at least .004″ adjustments with no discernible backlash using a dial that can be zeroed out at any time. Each of the easily visible increments on the black dial is equal to the thickness of a typical sheet of paper.

I do not have a device to measure vertical alignment as described in the article, but this is not likely to be a significant issue because the router base, which has been flattened on a granite surface plate using sandpaper, attaches directly to the MDF that is manufactured to excellent tolerances of flatness and thickness.

It is necessary to squat to reach under the table to attach the router motor and to make height adjustments. I do not mind a bit, but for those who prefer to avoid the latter, Bosch makes the router base usable with a simple hex key to allow height adjustments from above.

My intent is not to disparage the fine products reviewed in the article, but rather to demonstrate that there is a different, simpler way for those who might prefer. This router table system works – it allows me to build what I want.

[By the way, I disavow the detail in the plan drawing of the shop on page 58-59 of the same issue, which shows the woodworker’s router table with an insert plate and an insert ring. He also doesn’t own a two-wheel grinder and he wouldn’t lay a plane on its side. Nice shop though.]