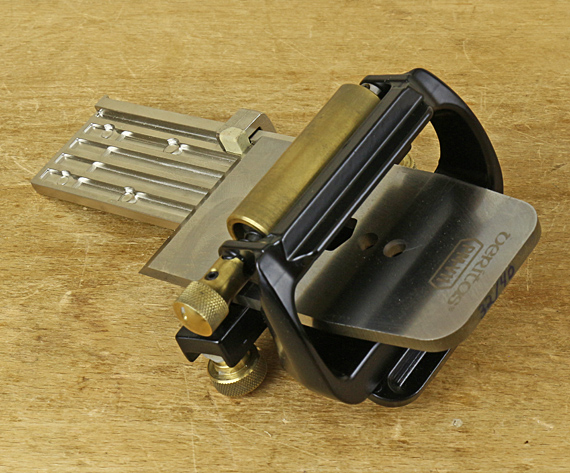

To create higher attack angles, such as 55°, to reduce tearout with a bevel-up smoothing plane, here are more advantages to a 20-22° bed angle versus the commonly produced 12° bed angle.

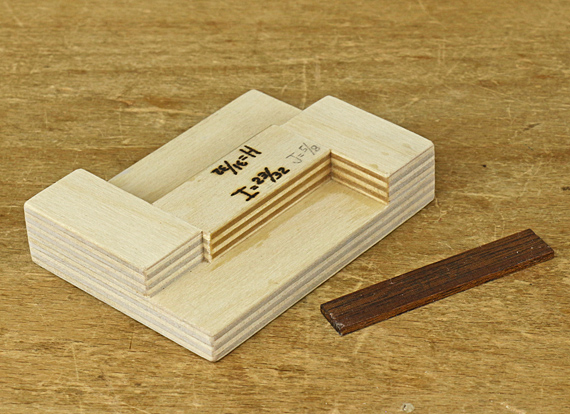

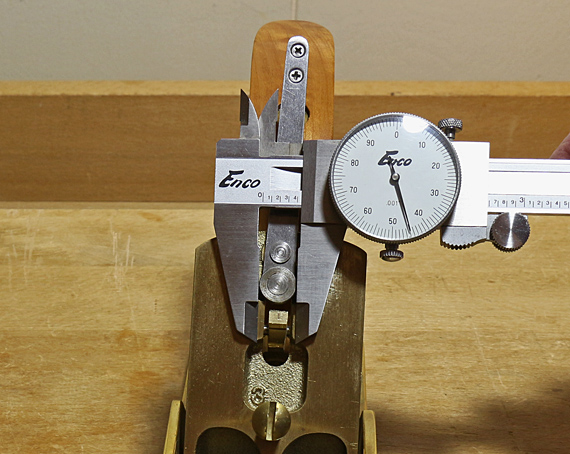

1. A higher bed angle requires less camber in the edge to achieve a given “functional camber.” Please see my post that defines the terms I am using and explains the simple math, and this post that shows the effect of bed angle. A blade placed in a 12° bed requires about 75% more “observed camber” to achieve the same functional camber as when placed in a 22° bed. For example: you must grind .014″ camber to achieve .003″ functional camber in a 12° bed, but only have to grind .008″ to achieve the same .003″ functional camber in a 22° bed.

Putting camber in the blade edge takes time and it’s easier to do if there’s less of it.

2. As the wear bevel develops on the lower (flat) side of the blade, an adequate clearance angle is maintained longer when the bed angle is greater. Again, I reference Terry Gordon’s article in Furniture and Cabinetmaking magazine (November 2018, Issue 276, pp. 48-50) and Brent Beach’s website.

Here are two more possible advantages to a 20-22° bed versus a 12° bed, but these are speculative.

1. For a given attack angle, the narrower sharpening angle (as would be used with the higher bed angle) may produce less resistance in the cut. I’m not sure. Maybe resistance is instead determined only by the attack angle, as has been suggested to me by a planemaker. I do not have a way in my shop of making an apples-to-apples comparison. I’d need two planes, identical except for bed angle, then make the same attack angle in each – for example, one with a 22° bed and a 33° blade (=55°) and the other with a 12° bed and a 43° blade (=55°).

2. Perhaps the steeper 20-22° bed is an advantage in design and manufacturing in that it is sturdier and less likely than a 12° bed to deflect downward. I don’t make planes, so I don’t know.

Coming up: just a few more points.