Wood, and thus wooden joints, moves with moisture changes, and since we put pieces of wood together with glue, it is worthwhile to consider if the glue itself flexes. In other words, how elastic, or stiff and brittle, is the glue itself?

Here, I want to look at differences among PVA glues, which in almost all discussions get lumped together without attention to significant differences among them in the property of flexibility. Here is a nice simple demonstration.

As background, we know that at one extreme, urea formaldehyde glue such as Unibond 800 forms a rock-hard, extremely strong, rigid glue line making it the best choice for bent laminations. Hide glue also forms a quite hard, rigid glue line. PVAs are, in general, more flexible.

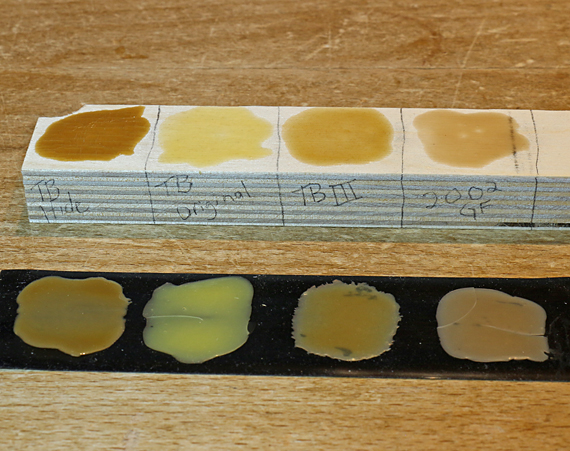

I spread four different glues into approximately one-inch discs on a birch plywood scrap, and then let them dry thoroughly for several days (photo above). From left to right:

Titebond Liquid Hide Glue

Titebond Original PVA

Titebond III PVA

Lee Valley 2002 GF PVA

The Lee Valley glue is a PVA that is claimed to have gap filling properties. I have had good results over many years with this product. Titebond III is touted for its water resistance and as a good all-round wood glue.

Working on the discs on the plywood, I could not dig my thumbnail into the surface of the hide glue. Even pushing as hard as I could, I could not make a mark. The surface also cracked as it dried.

The Titebond Original was the second hardest, taking a lot of pressure to make just a trace of marks. Titebond III was clearly the softest of the four; it was easy to dent with my thumbnail. The Lee Valley 2002 GF was intermediate between the other two PVAs.

I also spread discs on a piece of silicone “tape” (non-adhesive wrapping). After they dried for several days, I gently lifted the discs away, which had almost no adhesion to the silicone. I then curled and snapped them (photo below).

The results were consistent with the thumbnail test. The hide glue was the most brittle but Titebond Original was a pretty close second place. 2002 GF was intermediate; it could snap or curl depending on how I deformed it. Most interesting, Titebond III did not snap at all. No matter how I deformed it, it was quite flexible and only curled.

The simple point here is to show that there are distinct differences in flexibility among PVA glues. How you use that information is another matter. Depending on the type of joint, its dimensions, the wood properties, and the intended use of the piece, you may want more or less glue flexibility.

Also, this is a separate issue from the strength of the glue bond. There are also several other properties of glue to take into account when choosing among them.

Now this is obviously not a scientific test. However, I trust my observations in the shop and watching how pieces fare over the years as much as I trust some of the elaborate tests in woodworking magazines. My personal take away is this confirms what I noticed about Titebond III, which is that it is quite flexible, and so I’ve learned to avoid it in certain situations. Titebond Original is a better choice when you want a more rigid glue line and water resistance is not important.

Besides bent lams, in what situations would one want more or less flexibility in the glue line?

Hi Jim,

Some examples:

A rigid glue line is also good for veneer work, drawer facings, and a must for bent lams.

A sizable mortise and tenon joint contains significant dimensional conflict, especially with flatsawn frame pieces. One approach is to pin the joint near the shoulder to keep the shoulder seam tight, while letting the tenon move a bit in the interior of the joint with a slightly flexible glue line.

Edge joints often contain more dimensional conflict than they should, so a flexible glue line helps to accommodate that.

In all of this, we have to remember that wood has some elasticity too. It is also susceptible to compression set – permanent deformation under stress.

Sometimes the behavior of joints defies the supposed rules, and there are often multiple factors affecting the longterm integrity of the joint. I think the best way is to observe woodwork in the wild:

https://www.rpwoodwork.com/blog/2021/04/22/you-can-observe-a-lot-just-by-watching/

Also, observe your own work that you keep, while you hope for the best for your work that others own.

Rob

Jim, this was the exact question I had.

Rob, thank you for the thorough addition to another insightful article.

Jonathan