A reader described the following frustration he is experiencing with end grain shooting.

“I have a problem getting perfectly square ends when shooting them on my shooting board.

“I have a homemade plywood shooting board and use a Record 5 1/2 on its side to shoot. I’ve checked everything, and everything is square to each other and the plane is sharp, however when shooting end grain the plane takes more off the near edge (closer to the front) than the back edge.

“Am I doing something wrong?”

If you are getting this inaccuracy despite having everything set up square and true, the glitch may be in the shooting stroke itself. The blade can grab the workpiece on initial contact and slightly pivot it away from the fence at the opposite end. This can easily happen with wide workpieces.

But first let’s check a few things with your set up.

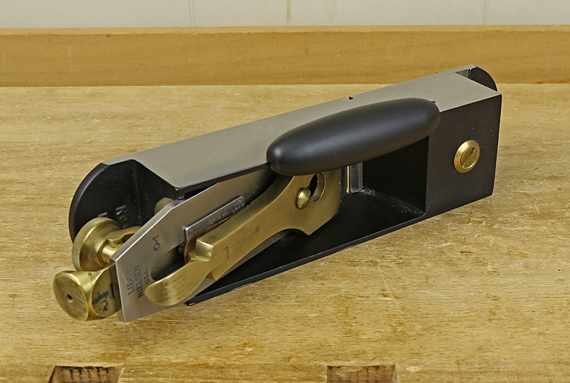

The sole of the plane should be flat, at least in the critical areas. Use a very wicked sharp blade with a straight, not cambered, edge, and a fine, even blade projection.

The track edge that the sole of the plane runs against in the shooting board must be straight. Ideally, the shooting board should have a snug channel in which the plane travels to prevent it from deviating during its run. (This will not work with a bench plane with a rounded side hump but not as well as with a dedicated shooter.) Wax the channel and/or use UHMW plastic on the running surface. If your shooting board does not have such a channel, take extra care to hold the plane firmly (without tipping it) against the running edge throughout the shooting stroke.

The fence must be straight, of course. The best way to square the fence is to place the sole of the plane (with the blade retracted) firmly against the track edge, then place a square against the sole of the plane and the fence. This directly assesses the elements that produce the square edge on the workpiece. The fence has to tolerate considerable pressure in use, so make sure it is fastened securely.

The fence also has to be long enough to register an adequate length of the workpiece so the workpiece does not budge during the planing stroke. I sometimes had problems with my old shooting board that had a fence that was too short. My current shooting board’s fence is 11 1/4″ long. Books often show shooting boards with a fence that is too short for furniture work.

A grippy glove on the hand holding the wood is a huge help in keeping the workpiece steadily registered and in advancing it after each cut. Otherwise, inaccurate registration can creep in, especially with wide workpieces, and especially as you fatigue. As a diagnostic experiment, try positioning a workpiece just right, then clamping it in place, shoot, and see if you get a square edge.

In summary, your shooting “machine” must be set up accurately, but also must be dynamically stable in use.

Mystery frustrations like this reader is experiencing afflict all of us woodworkers but are rarely addressed in books and other teaching media where the descriptions are often idealized. Rest assured, however, there are solutions.

I hope this helps, dear reader, but if you are still stymied, let me know. We’ll get it right.