The only fully meaningful tests of a sharpened edge are its performance and endurance in its assigned task. Nonetheless, at the sharpening station it is convenient to use surrogate tests to evaluate the fresh edge. Even with high confidence in your sharpening procedure, it is helpful to ensure the edge meets your expectations before you put it to work. This is especially so for plane blades.

I do two evaluations. Most important, I look at the edge. The irony is that being able to see it means it probably is not good enough.

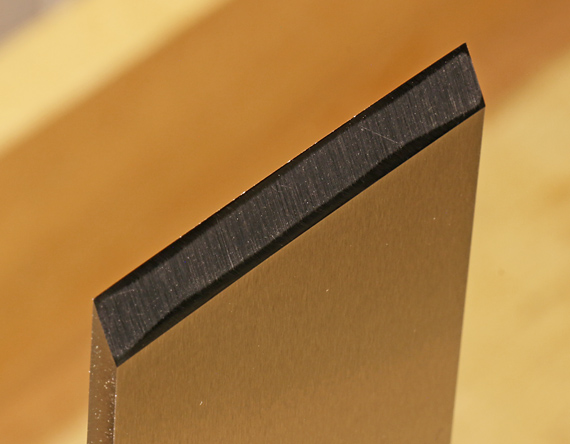

Look almost straight on at the edge under a bright light, preferably with magnification, and try to catch a reflection off the edge. I use the large, low-power lens in the articulating art lamp at my bench. Play the blade under the light, searching for a reflection. If it is really sharp, there is none to see. This is difficult to photograph, but the O-1 edge shown above is about as pristine as it gets. The narrow secondary bevel and a few dust particles are visible but the edge is clean and invisible.

Examine all along the edge. It may be fine except for a defective blip that reveals itself by reflecting light. That may be acceptable for a mortise chisel but an unwelcome frustration for a smoothing plane blade going to work on pearwood. Below is a used edge with several obvious blips, even though the rest of the edge is pretty sharp.

Because the endpoint of this evaluation is a negative observation, and there are probably differing levels of sharpness within that, I like to also have some positive demonstration of the edge’s capability.

My preferred functional test is to shave hair on my arm. I gently bring the edge up to just a few hairs. For a smoothing plane blade, for example, I want to see those hairs well-nigh pop off with minimal pressure. I find the amount of pressure needed to cut hairs is a good indicator of sharpness. Using hairs growing at different angles or of different stiffness can be even further revealing. With just a little experience, it becomes easy to reliably differentiate high levels of sharpness. After all, we intuitively use this sense all the time when shaving with a manual razor.

If the edge performs well on the hair test and the sight test does not show defects, I’m happy with it. For easy sharpening jobs such as chisels, sure, it’s often adequate to just trust that my usual sharpening sequence produced a good edge. For almost all plane blades, however, I do test the edge visually and functionally before putting it to work.

All of this assumes, by the way, that geometry of the edge is satisfactory – squareness, camber, and angles, as appropriate.

Some woodworkers are comfortable with other tests. A good one is to pare the end grain of a soft wood. Little pressure should be needed to make a very thin, clean slice without collapsing the wood’s vessels. Practice will soon reveal how a very sharp edge acts in this test.

Another method is to see how low an angle you can engage the edge as you slide it along your fingernail. I don’t like aiming a sharp tool toward my cuticle. The barrel of a plastic disposable pen is a better, safer test surface.

One method that I do not think is useful is to feel the edge by brushing your finger across (not along!) it. Yes, you can tell a really dull edge from a decent one but I do not find this is a good way to differentiate high levels of sharpness needed for woodworking.