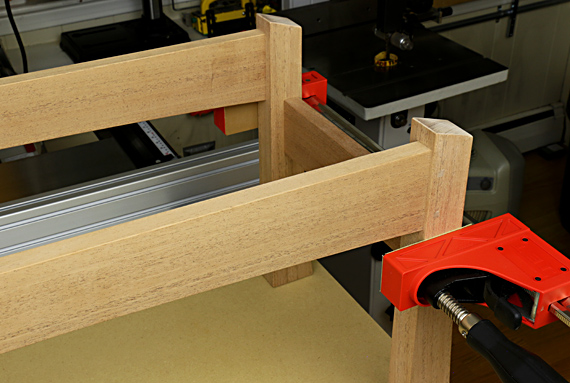

You’ve cut your joints, fitted them individually, and happily found them to be tight and true. Now you dry assemble the frame or carcass, which should include applying the clamps to rehearse the conditions under which the glue will dry.

Unfortunately, you may well find that despite the rightness of the individual pieces and joints, and having applied the clamp forces in true directions, the assembly is out of square, twisted, or harbors some other seemingly unmerited vileness with which you must now contend.

What’s going on? Well, I suppose tiny tolerances, wood movement, unnoticed error stacking (and probably the alignment of the planets) have somehow militated against the righteousness of your assembly. As careful as I try to be, I find at least a little bit of this is not the exception but the norm.

So, the next step is to tweak the clamp placements to true the assembly. For example, you can use pinch rods and recall the rule of the long diagonal.

But how much should you force the assembly into true? Consider that you are probably using several clamps, each capable of perhaps a thousand pounds of force, which can easily bend and twist wood. You may be truing one aspect of the assembly while distorting another, making it impossible, for example, to later get a good sliding fit with a drawer.

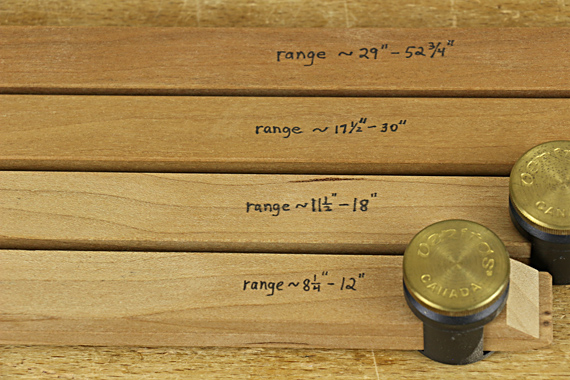

Clamp force can also compress wood, especially on side grain where it meets end grain, which is part of most joints. I think a little bit of this nearly always happens in clamped glue ups and acts as an acceptable correction mechanism. Carried too far, however, I suspect it may show up next year as gaps at the joints because the glue line has some elasticity, especially with PVA glue, and the wood compression may not be fully elastic.

The point is to not add too much stress to the final assembly by using clamp force as a correction mechanism. As much as possible, the components of the assembly should “want” to go together true, flat, and square. Very small corrections by clamp placement to true the assembly during glue up will likely not cause problems, but overwhelming a fundamentally untrue assembly with clamp force is not a good approach. Neither is making joints so loose that they can be easily forced into any configuration.

If the assembly requires anything more than gentle correction with clamps, go back and tweak the joints and/or components if possible. As examples, judiciously trimming tenon shoulders will solve many frame constructions. Dovetail assemblies can sometimes be tweaked by planing the inside face of the tail board, or easing overly tight spots in the joint itself.

Finally, keep in mind that you can also compensate for some imperfections in the glued-up assembly. For example, a slightly twisted frame-and-panel for the back of a cabinet can usually be easily held flat by the cabinet itself without significantly stressing the carcass. On the other hand, a slightly twisted cabinet door or box lid is difficult to fully correct directly, so it is usually easier to plane the front edge of the carcass (preferably before glue up!) to accommodate the twist in the door.

Every situation is different, but the general principle is: don’t force it much! Try to use good stock preparation and joinery, make judicious corrections as needed, and think through how remaining imperfections might be accommodated. And maybe you’ll find the planets to be aligned in your favor after all.