The usual directive is to flare the end grain mortise walls and wedge the tenons against those walls, as in the photo above. With the opposite configuration, which has the side grain mortise walls flared, there is reasonable concern that the wedges might exert pressure across the grain of the mortised board sufficient to split it.

However, there is another important way to consider this joint.

In the conventional configuration (photo above) with a well-fit joint, strength is created by the glue bond of the long grain-to-long grain interfaces, which are not wedged. In the long grain-to-end grain interfaces, which are deficient as glue surfaces, strength is created by the mechanical action of the wedges. Thus, all four interfaces contribute to the strength of the joint.

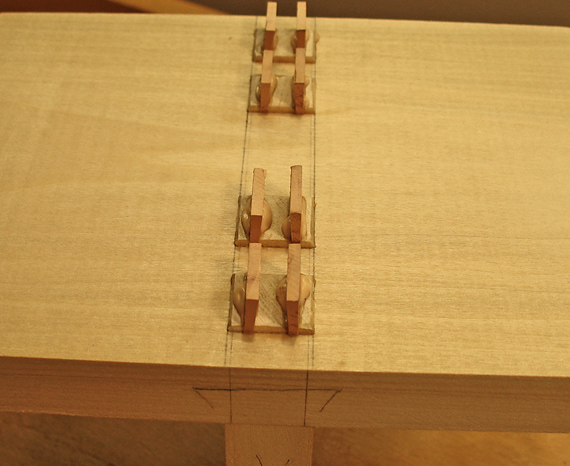

In the opposite configuration (as in the photo below), the wedges apply some “clamping” pressure for the long grain interfaces, but I would contend that is largely superfluous. At the same time, the long grain-to-end grain interfaces are mostly wasted as strength components.

Therefore, to maximize the strength of this type of joint, the conventional wedge configuration is better. In all cases, I think it is best to clamp across the joint and then insert the wedges.

Now, realistically, splitting is not likely in the opposite configuration with judicious wedging, especially if the joint is not too near the edge of the board. And the multiple mortise and tenon joint is probably more than strong enough in either configuration for its typical applications. Still, it is a labor intensive joint and one therefore tends to minimize the number of tenons, so it pays to get the most strength from each one.

The whole point here is to think about what is actually going on in the design of the joint, and make rational choices.

You can find step-by-step instruction on making this joint in my article, Making Multiple Through-Mortise-and-Tenon Joints, in the August 2008 issue (#170) of Popular Woodworking magazine. By the way, an important aspect of my method is to not use a fully housed tenon board as is often advised.

We should not be too definitive about these matters because each piece has different requirements for strength and appearance, and other factors inevitably influence both. Interestingly, in the same issue of PW, Bob Lang uses dual M&Ts to join shelves to the sides of a bookcase, using an approach very different from mine. Yet, I’d bet his bookcase is still going strong.

[Photo of the “opposite” configuration courtesy of Mark Ketelsen.]