Handplaning thin boards, those less than about 1/2″ thick for most species, sometimes produces surprising frustration. The solution to many problems is to consider what is happening on the underside of the work piece.

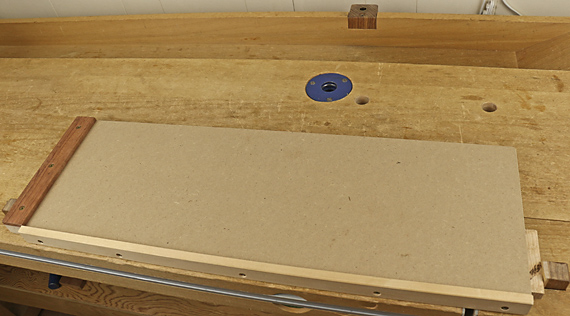

I usually plane such wood, for example, a thin drawer bottom, on a very flat planing board with front and side stops only about 7/32″ high, or on a nice flat section of my workbench against a low-profile planing stop that inserts directly into the bench. This avoids distortion from the pressure of bench dogs and gives me a better feel for how the plane is meeting the wood.

The handplane sole acts somewhat like the feed rollers in a thickness planing machine. It presses on the flexible board and forces it downward to close gaps under the board. This effect varies, sometimes unpredictably, with the length of the plane and the skew angle of planing.

Suppose now we are trying to smooth plane the surface of a drawer bottom or panel and the underside is a bit concave. (Here I do not mean an even-thickness board that is simply cupped a bit.) A finely set plane will miss areas on the topside that are over the concavities underneath.

This is especially annoying if you are trying to clean up a few spots of tearout and the plane keeps missing them. The tolerances involved are quite small because in these situations the plane is trying to take a very thin shaving, say .001″.

The solution is to be cognizant of the interaction of work piece and the work surface, and resort to good old shims. Sometimes I’ll use blue tape but more often just a few shavings stuffed under the board. or even some paper.

In fact, this little trick is handy even if the thin board is perfectly flat and you want to raise a small area to plane away a defect without having to plane down the whole surface just to hit the defect.

When using a shim, it usually is helpful to dog the board to keep the ends down and thus push up the shimmed area.

Note that if the work piece is of even thickness and just a bit cupped, this will usually not be an issue. The board will flatten against the bench as it is being planed, all areas will be hit with the plane, and the board will simply spring back to its cupped state when you are done planing. Within limits, that is not a problem because the panel will usually be easily coaxed into flatness by the frame or drawer grooves.

So, the real key in all of this is to not take your handplaning setup for granted but rather to be aware of the actual interaction between a finely set handplane blade, the plane sole, the work piece, and the work surface. With this awareness, it’s just a matter of common sense to diagnose and fix what otherwise could be vexing problems.

Nice.